More and more independent projects are going online to find funding. Is it working?

By Alex Gurnham

At some point after the whole global market collapse, the economy stopped being known as the economy. There was a small but significant linguistic shift, the branding of a new catch phrase denoting the financially difficult times. Nowadays, the economy doesn’t exist. Instead, we’re dealing with this economy. As in, “good luck finding a secure job in this economy.” Or, “that project sounds awesome, but it just isn’t realistic. Not in this economy.”

At some point after the whole global market collapse, the economy stopped being known as the economy. There was a small but significant linguistic shift, the branding of a new catch phrase denoting the financially difficult times. Nowadays, the economy doesn’t exist. Instead, we’re dealing with this economy. As in, “good luck finding a secure job in this economy.” Or, “that project sounds awesome, but it just isn’t realistic. Not in this economy.”

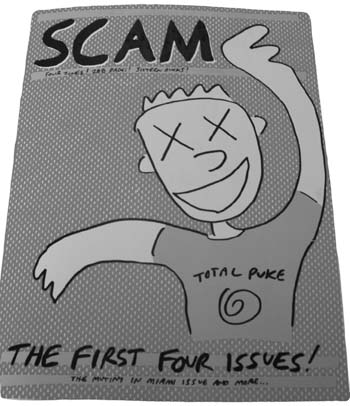

So when Erick Lyle, creator of the iconic punk zine SCAM, Biel, head of Microcosm Publishing, got together to reprint first four issues in a single volume, they approached the project with a slight amount of scepticism. Biel, not a fan of the zine anthology format, wanted to ensure reproduction would be of highest quality, offering time fans a product that did more than simply recreate the original issues. The result was Biel calls “a big, heavy book,” clocking in at nearly 300 full size pages and costing roughly twice as much as the average Microcosm publication to print.

It was a bold venture to take on. Especially in this economy.

“We had our annual meeting where we all travel out to Bloomington in April and we were in a really bad spot financially,” Biel explains. The SCAM anthology was Microcosm’s next scheduled project, and it didn’t appear the funding would be in place to achieve the vision Lyle and Biel had for the book. The solution would come from staff member Chris Lynch in the form of the website KickStarter, a funding platform for indie artists and companies.

KickStarter is a crowd funding website, a central hub of independent works-in-progress that interested donators can support. The site makes it easy to customize your campaign. You can include videos showcasing your cause, dole out rewards to donators or link your project to similar ones supporters may have already invested in. KickStarter’s appeal also comes from its popularity, its brand recognition. It’s a place where people feel comfortable giving money. Nearly 3,000 projects have been successfully funded through the site since its launch in 2009, ranging from under $100 to tens of thousands of dollars. It’s a tool, as Biel says, that offers “a mythical kind of promotion to reach to its own audience filtered through your networks.”

The SCAM campaign went live following Microcosm’s annual meeting and was promoted through their store, newsletter, website, Facebook and Twitter accounts, a wide sweep meant to reach any and all interested parties. The response was dramatic. Within a few months Microcosm reached its $5,000 goal, funding nearly half the project costs through the KickStarter campaign. Donations came from a host of sources, likely and unlikely, network of supporters previously unavailable to the company. “A big part of the appeal is to get people involved who would never buy our books normally,” Biel says. “Whether those are people I grew up with, people who are familiar with Microcosm but don’t frequent our website, or people who want to help us financially. I feel like those are all really important people that any organization struggles to reach.”

Biel’s efforts are indicative of a larger trend within the world of the independent arts. As government and other funding avenues continue to dwindle, more and more artists are turning directly to their audience and friends for support. KickStarter and other online tools, including other crowd funding sites like the popular IndieGoGo and the usual social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter, help to enable this shift: why wait for a grant when you can source your funding straight from the masses?

“The Internet is awesome,” says Laura Roberts, author of the self-published Naked Montreal. “Publishers don’t even know what hit them; they should be prepared for the tsunami of excellence coming their way.” Roberts is using her website in conjunction with Twitter and Facebook to run a fundraising campaign for Naked Montreal, a fictional romp through the city’s sexual underground. A writer and columnist, she tapped into the connections she made through years of journalistic work in the attempt to fund the printing of her book. And the supporters are there, says Roberts, in the form of “perverts, nerds, bookworms, sexy librarians, sexperts, sex workers, nymphomaniacs, beautiful people, Montrealers, fans of Leonard Cohen” and anyone else who enjoys great raunchy literature. She attributes her success partly to the nature of her book, its subject matter and “hot female narrator,” but also recognizes the ability of digital tools to reach like-minded audiences in ways that weren’t previously possible.

The sites and methods may vary, but the idea of reaching out through the web to seek donations to help bring a project into being is becoming increasingly common. The Tyee, a British Columbia based journal of news and culture, raised nearly $15,000 from readers for their annual set of fellowships in Investigative or Solutions Reporting, awarded to prospective journalists seeking to work on a series of articles on important local issues. Filmmakers Kyle Wilson and William Allinson, creators of the horror/comedy film I Spyders, employed the fundraising site IndieGoGo in the effort to balance their ambitious budget and drum up preliminary interest in the film. At the core of each of these projects, just a small sampling from the ocean of similar campaigns springing up all over the place, is a belief in the willingness of people to support a worthy artistic cause. All they need is to be made aware of it.

These campaigns for support aren’t solely focused on finances, however. Intrinsically built into each effort is the development of an audience, or, more appropriately, a community. Donators not only become guaranteed product purchasers, sometimes they are even invited to become actively involved in the work they’re supporting. What people are investing in is not a book, movie or store, but the ideas behind them and their development. Inevitably, that development is something each donator becomes personally invested in, not just financially.

These campaigns for support aren’t solely focused on finances, however. Intrinsically built into each effort is the development of an audience, or, more appropriately, a community. Donators not only become guaranteed product purchasers, sometimes they are even invited to become actively involved in the work they’re supporting. What people are investing in is not a book, movie or store, but the ideas behind them and their development. Inevitably, that development is something each donator becomes personally invested in, not just financially.

“The benefit of crowd funding is that everyone who donates to the production is a guaranteed future audience member who can help get the word out,” says Allinson, the director of I Spyders. “With even a small financial stake in the film, people will become involved as they get to see where their money is going with production updates, behind the scenes access and a finished copy of the film — additionally, if we create a product that satisfies our contributors, we will have created a database of people that we can revisit with future endeavours.” The connection built between artist and audience is based on a mutual interest, a common goal in seeing the potential project come to fruition. It’s a heightened relationship that often has a profound effect on the finished product.

It is that heightened control of content production that motivates the majority of readers to donate to the Tyee’s Investigative or Solutions Reporting Fellowship as well. When making their contributions to the fund, readers are encouraged to identify issues they would like to see covered, suggestions that go into identifying the categories to which applicants can apply. The process gives both the Tyee and journalists a strong sense of the issues their community is concerned with, and what coverage they should be striving for.

The I Spyders crew takes this concept to a different level in their campaign, offering production credits, behind the scenes tours and even some limited creative input to donators at certain tiers. “We want anyone that contributes to the project to get something out of it, whether it be a special thanks at the end of the film to an Executive Producer credit at the beginning,” Wilson says. “It’s a chance to connect with the director, crew and actors and show our appreciation for their donation.”

Of course, there are downsides to these techniques. Sites like KickStarter and IndieGoGo charge small fees and feature a vast array of projects, occasionally causing smaller efforts to get lost in the masses. And sometimes it just doesn’t work. Most of Toronto’s indie book and magazine lovers are most likely aware of the spring campaign run by the This Ain’t The Rosedale Library bookstore. The Toronto landmark tried to chip away at a rental debt by hosting events and appealing online for PayPal donations, but, despite a loyal following and a successful campaign, owners Jesse and Charlie Huisken still found their formal proposal to their landlord rejected and were forced to close the store’s doors in late June. Circumstance is still capable of trumping the most dedicated efforts.

In the end, it comes down to luck and trust — and trust usually has to be earned. Perhaps that’s why when asked about the success of the SCAM campaign, before going into the new technological forms and networking possibilities, Biel references the 20 years Lyle has been active in the zine community and the 15 years Microcosm has spent building an audience that respects its work. There’s an element of trust and mutual respect between artist and audience that’s absolutely necessary in gaining this kind of support. “We’ve often found,” Biel says, “that when we ask for donations that we actively need, people do respond.”

Even in this economy.