Hate is a part of zine history.

What can skinzines tell us about the far-right today?

by Amanda Rogers

Cover art by Anjela Freyja

“Annie Sprinkle? Annie Sprinkle?! I can’t believe they actually used this!”

Ashley’s own face looked back at her from the photocopy I had just given her, shortly after I’d snatched one from the crowd of protestors that were in front of George Tiller’s abortion clinic, where Ashley worked as a clinic escort. The flyer’s hackneyed design job wouldn’t look out of place amongst the cheap memes that flood digital media today, styled as a Western “Wanted” poster with a bounty. But this was the mid ’90s in Wichita, Kansas, at the apex of the so-called Abortion Wars in North America.

At the time, serving as a clinic escort in the face of domestic terrorism campaigners was something of a feminist rite of passage for my high school friends. It was not for the faint of heart. Hostile demonstrators, including affiliates of the heavily armed white supremacist groups Christian Identity and the Army of God, were highly activated. Members routinely harassed, threatened, and attacked anyone who worked in support of reproductive rights, including clinic escorts, patients, nurses, and police guards. Their biggest target was Tiller, who was later assassinated by an Army of God member.

To protect themselves, young escorts like Ashley would adopt a playful alias, often doubling as a means of trolling, and these chumps had fallen for Ashley’s improbable choice of “Annie Sprinkle.” For context, this was during the period that Sprinkle, a sex educator and feminist activist from California, had gained fame on the talk show circuit promoting her books and made headlines as the first porn star to earn a PhD. But Ashley? She was a quintessential Midwest gutter punk, known for hopping trains, fighting cops, and giving herself eccentric tattoos. On the flyer, she can be seen wearing a crooked cowboy hat, her messenger bag barely held together with crust punk patches and visibly overflowing with the Xeroxed pages of a yet-to-be-assembled new edition of her zine. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn she had pasted this very flyer image into a subsequent issue soon after, she got such a kick out of it.

This incident with Ashley was my first encounter with underground zine culture. In hindsight, it’s telling that it happened there on the front lines, where far-right political violence and leftist activism clashed so openly. Go to any typical zine fest or infoshop, and you might assume zinehood’s ideals of self-expression and consciousness-raising are the provenance of the liberatory left alone. Zine culture has always laid claim to a politics of “no compromise,” an underground subculture committed to the “resistance.” So naturally, DIY fanzines appealed to us, even back in Wichita.

But punk rock — the life force of the zine-making booms of the 80s and 90s — has always been a paradox, containing an avowedly racist skinhead faction and its anti-fascist counterpart all at once. I’d later learn that this split extended to zine publishing too. As lefty and anarchist punks raced to the copyshops, White supremacist skinheads did too.

Today, those who continue in radical self-publishing tradition are faced with a strange adversary, the globalized, highly digital white supremacist movement that you read about in the papers. New media has drawn new battle lines. But understanding what’s at stake — and figuring out what to do — requires confronting a deeply uncomfortable reality: hate is a part of zine history.

But punk rock — the life force of the zine-making booms of the 80s and 90s — has always been a paradox, containing an avowedly racist skinhead faction and its anti-fascist counterpart all at once. I’d later learn that this split extended to zine publishing too. As lefty and anarchist punks raced to the copyshops, White supremacist skinheads did too.

Today, those who continue in radical self-publishing tradition are faced with a strange adversary, the globalized, highly digital white supremacist movement that you read about in the papers. New media has drawn new battle lines. But understanding what’s at stake — and figuring out what to do — requires confronting a deeply uncomfortable reality: hate is a part of zine history.

∞

Skinzines

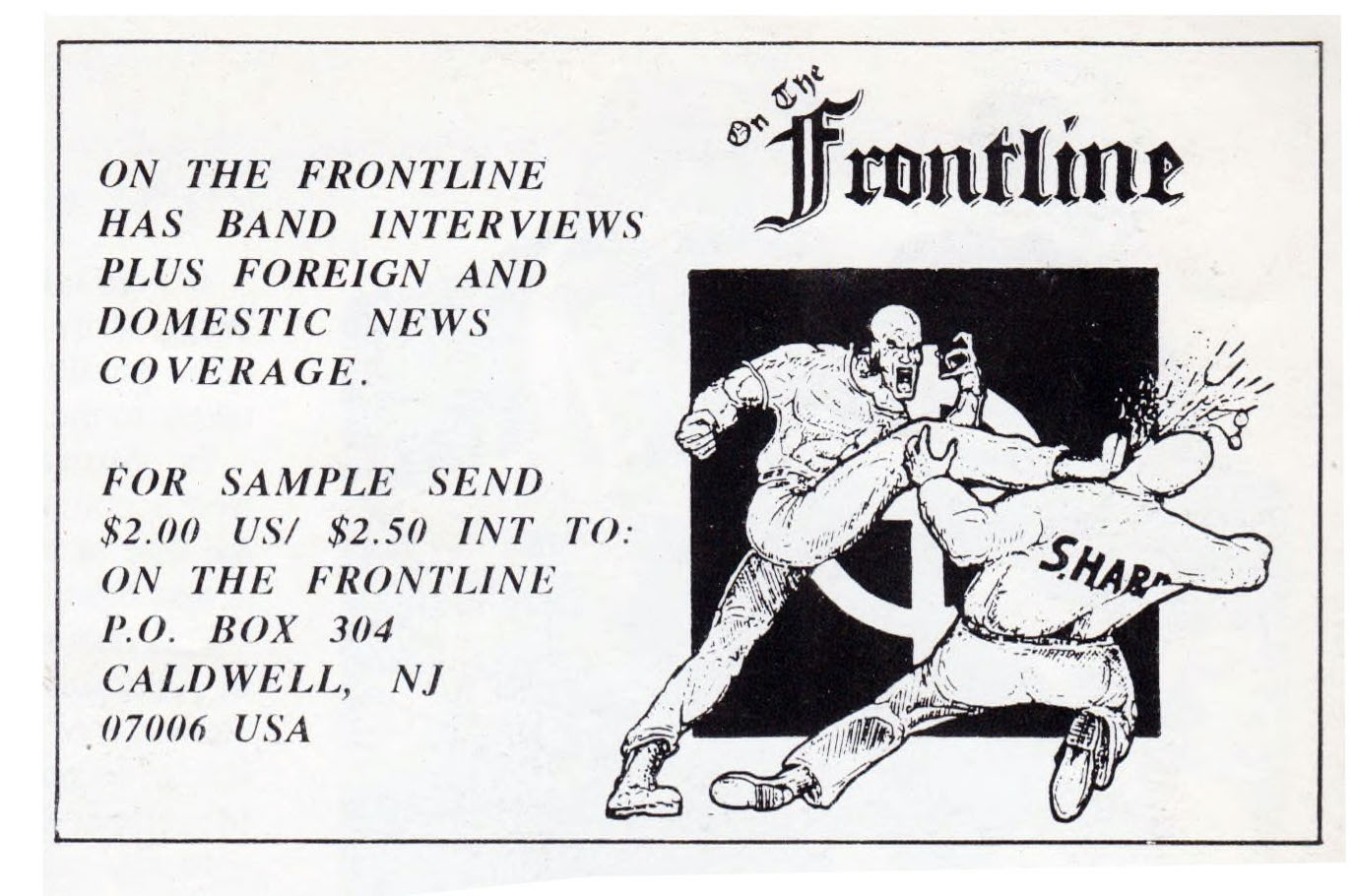

Skinheads occupy a curious place in the popular psyche, often remembered as a short-lived but scary phenomenon of Neo-Nazi punkers and criminal bikers. But within DIY music subcultures, racist skinheads and SHARPs (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice) endure, their legacy and present iterations never far from view. So how did we get here?

Before punk began in Britain, skinheads weren’t actually all that concerned with race. As an odd spin-off of London mod culture, the original skins also adopted some of their swagger from the dapper West Indian migrants who had become their neighbours in working-class neighbourhoods. Skinhead music remains heavily influenced by Jamaican ska.

That skinhead culture was on the verge of fading away in the early 1970s. Then, punk arrived. Hordes of white working-class youth were newly disillusioned by the conditions of a disastrously faltering British economy, and the genre’s combative, outsider ideals spread rapidly, appealing directly to this milieu. American punk, while outwardly pretty white, still staked its heritage in the tradition of homegrown Black music, tracing its roots to Black proto-punk pioneers like Pure Hell and Death, all the way back to the Blues. But in those British towns, punk’s rejectionist ethos fostered a different heritage identity for angry young men: the proudly nationalist, working-class skinhead punk.

A generation hardwired for scuffles and bound by a dark, outsider machismo, the second wave of skinheads refined their aesthetics into the more militarized style we recognize today — think combat boots, denim, bald heads, and bomber jackets. While there were skins who insisted on maintaining the mixed, urban roots of their subculture, a small and highly visible faction began instead to root their nationalism in rhetoric that was increasingly anti-immigrant, anti-gay, anti-semitic, and racist. The skinhead phenomenon has confused the rest of the world ever since, itself divided between those who are hardcore anti-racists and those erratic skins who do subscribe to a far-right and neo-Nazi ideology.

This shift towards extremism was no accident. The existing British far-right quickly recognized the mobilizing potential of the young skinhead demographic, and it invested. In 1983, the white supremacist National Front party strategically established its own record label, White Noise Records. The label’s launch was soon followed by the explicitly nationalist “skinzine” of the same name in 1986.

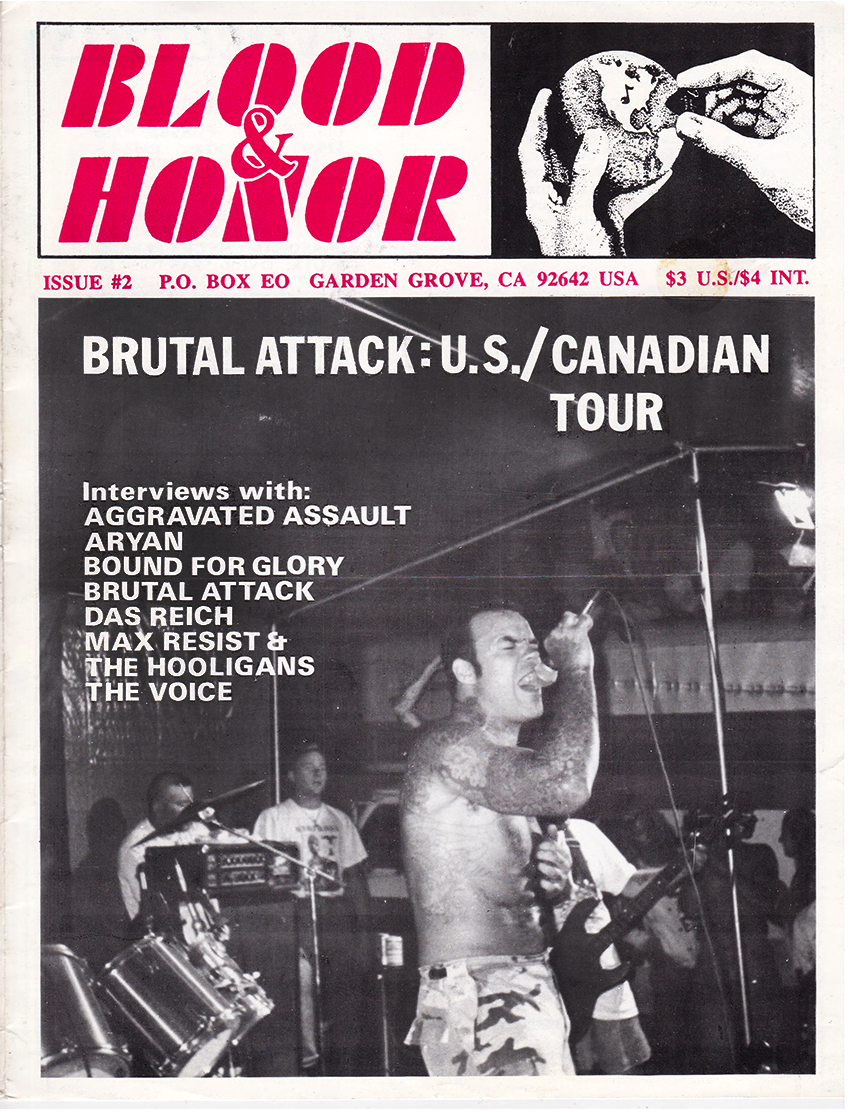

The National Front’s attempt to co-opt the British nationalist skinhead music scene, however, was not wholly successful, and not without its detractors. Disaffected members — led by notorious racist skinhead band Skrewdriver — broke away from these poorly cloaked political puppeteers in 1987. Their first order of business was to found their own rival zine, which would become punk’s most infamous white power publication: Blood and Honour. The name is taken from a German phrase inscribed on the knives issued to members of the Hitler Youth.

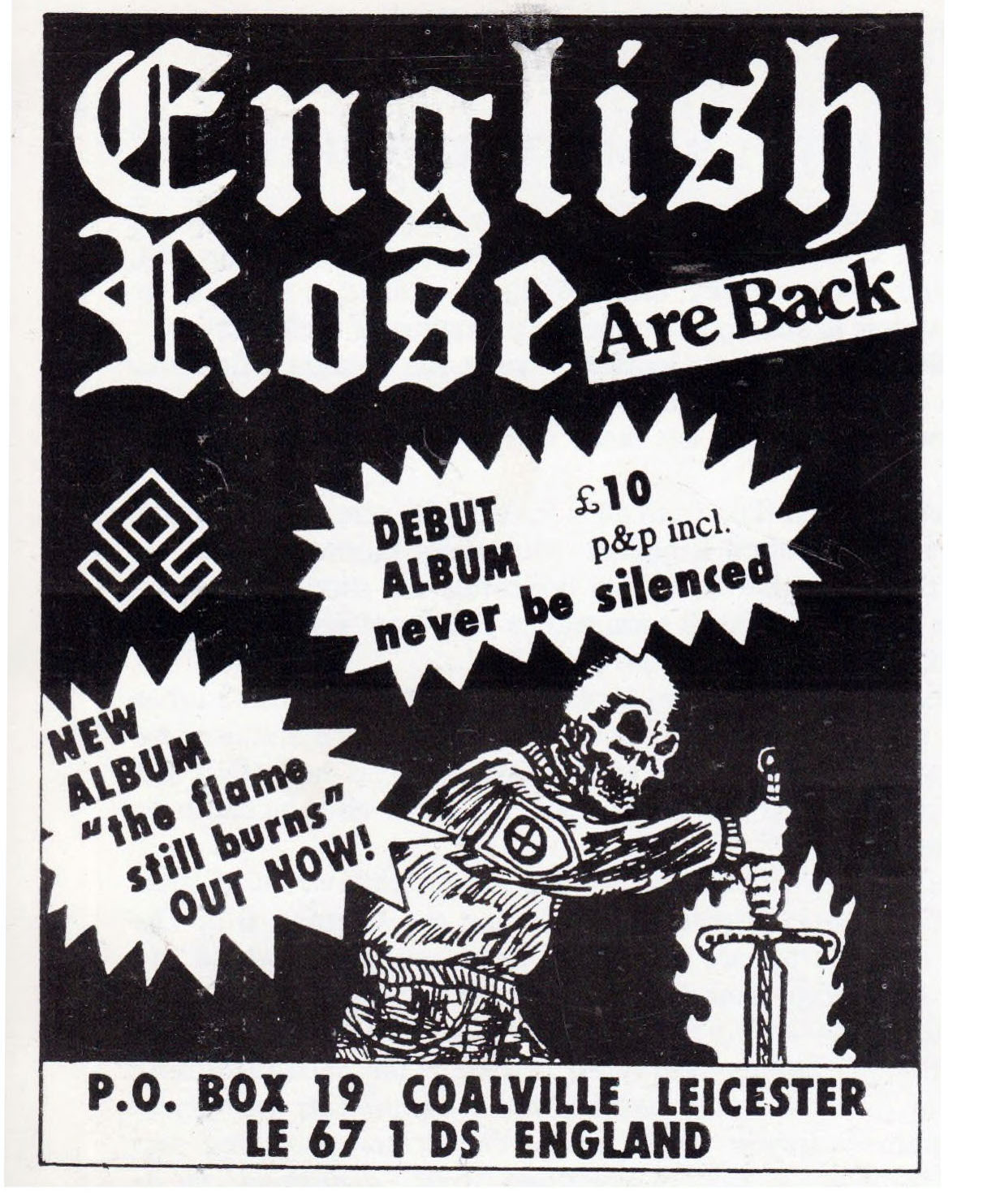

White power zines flooded the UK for the next ten years, with titles like Boots ‘n’ Braces, Final Conflict, British Oi! and Voice of Britain, circulating far beyond the small towns and industrial districts that produced them. These periodicals were music fanzines above all, promoting new bands, concerts, festivals, merchandise, and commentary. But the same set of talking points of so-called “nationalist” politics were rehearsed in virtually every issue, too.

Interestingly, an adjacent, somewhat more subdued strain of white power zines emerged without a focus on music nearly at all. Some, like Vanguard and The Order, were calls to action and current events compiled by far-right organizations. Neo-Völkisch zines, like the Kent Crusader and White Eagle, were equal parts Aryan mythology seminar and poorly edited small-town newsletter. These might be seen as precursors to the more recent National Socialist Black Metal zine scene, which has utterly thrived in parallel to white power punks.

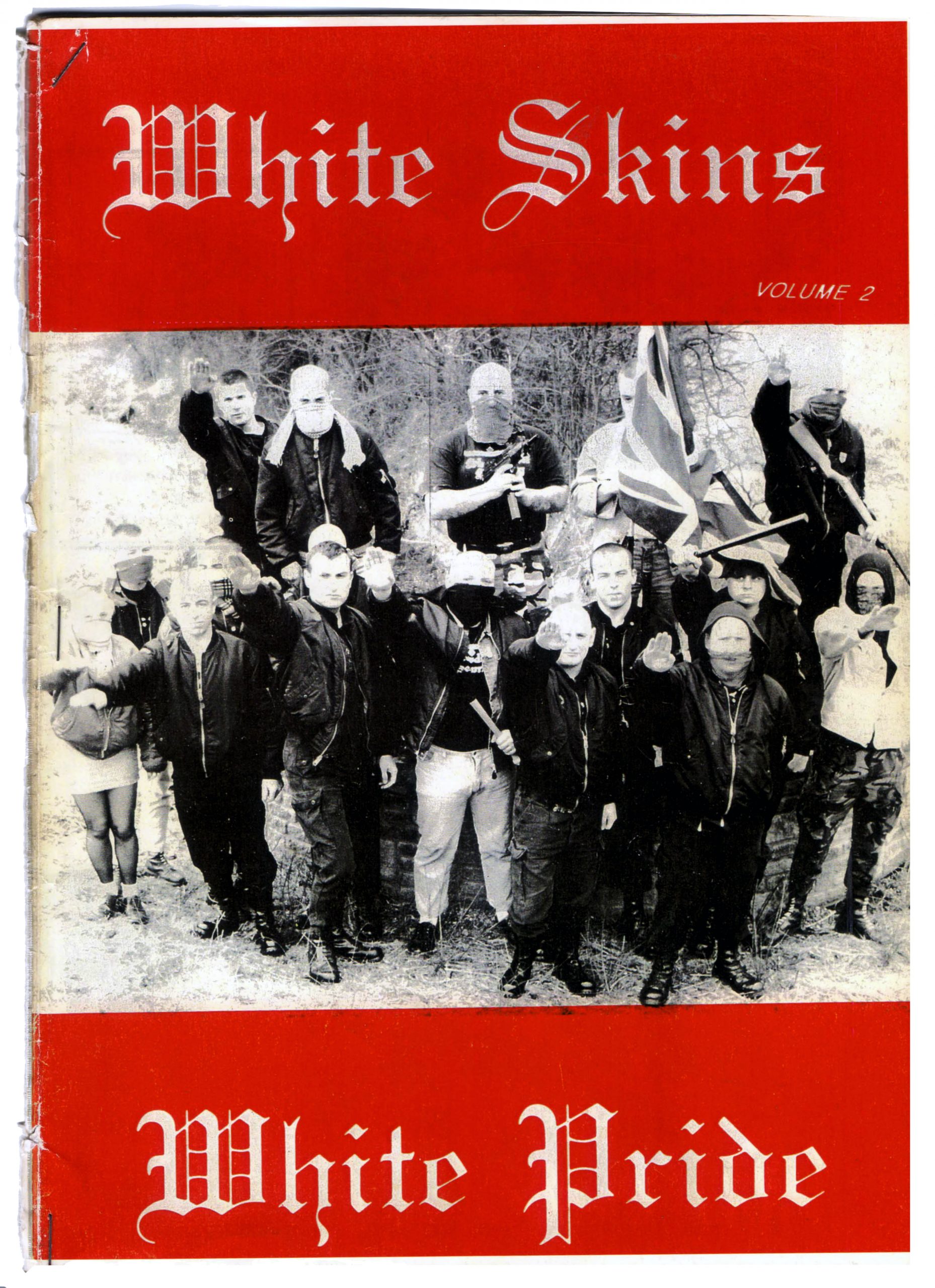

Whatever their focus, skinzines acted as a critical networking tool, something of a yearbook for white pride. Crews around the world could register their loyalty by sending in photos complete with flags, boots, and Nazi salutes. Fan letters abounded. Some skinzines were majority personals and society pages, full of images from local shows, but also news of skinhead births, weddings, and deaths (complete with many offensive cakes). Blood and Honour’s special edition photozine of this kind, White Skin, White Pride, was amongst the most popular titles of all. These spreads featuring skinhead socialites were key, providing a critical sense of belonging, loyalty, and identity construction to those involved. It also meant that skinhead culture took on a decidedly internationalist bent.

∞

Skin culture crosses the Atlantic

By the early 90s, youth neo-Nazi punk would come home to roost in the US. British skinzines and tapes came to find welcome readers in the mailboxes of the American Bible Belt and beyond. The failures of Ronald Reagan’s trickle-down economics and a surge in xenophobic rhetoric had packed the political powder keg. But it was paper media that would cause an imported brand of white nationalism to ignite across America, quickly spreading from the midwest and Texas out to the coasts, its torchbearers styled in boots, button ups, and cheap bomber jackets.

Although zines like Blood and Honour disseminated punk and skinhead aesthetics from the UK to the US, the newfound alienation in the American context proved even riper for an explicit embrace of white power politics. One skinhead, reminiscing about the early birth of his local scene, recalls the States as being far less restrained. “Skinhead in America was a bit different from the UK… Over here, I think we were scruffie, more of a gang. The violence was insane, just insane.”

This decentralized mobilization of gang-like American skinhead groups soon reached the West Coast, the spread largely thanks to California-based racist super leader Tom Metzger and his group White Aryan Resistance (WAR). While most simply feared skinheads, Metzger saw angry youths as the perfect recruits, bidding them to do his dirty work. He famously lauded them as the “shock troops” of the American white power movement.

“Skinhead in America was a bit different… Over here, we were scruffie, more of a gang. The violence was insane, just insane.”

Metzger himself self-published prolifically until his death in 2016, though his pamphlets and newspapers did not usually carry the brash markers of punk in their design. Rather, they were dense pages spewing unfiltered antisemitism and outlandish conspiracy theories. His projects like The Insurgent and WAR newsletter were perhaps more akin to the UK’s Pagan nationalist pamphlets than to the Oi! fanzines they complemented.

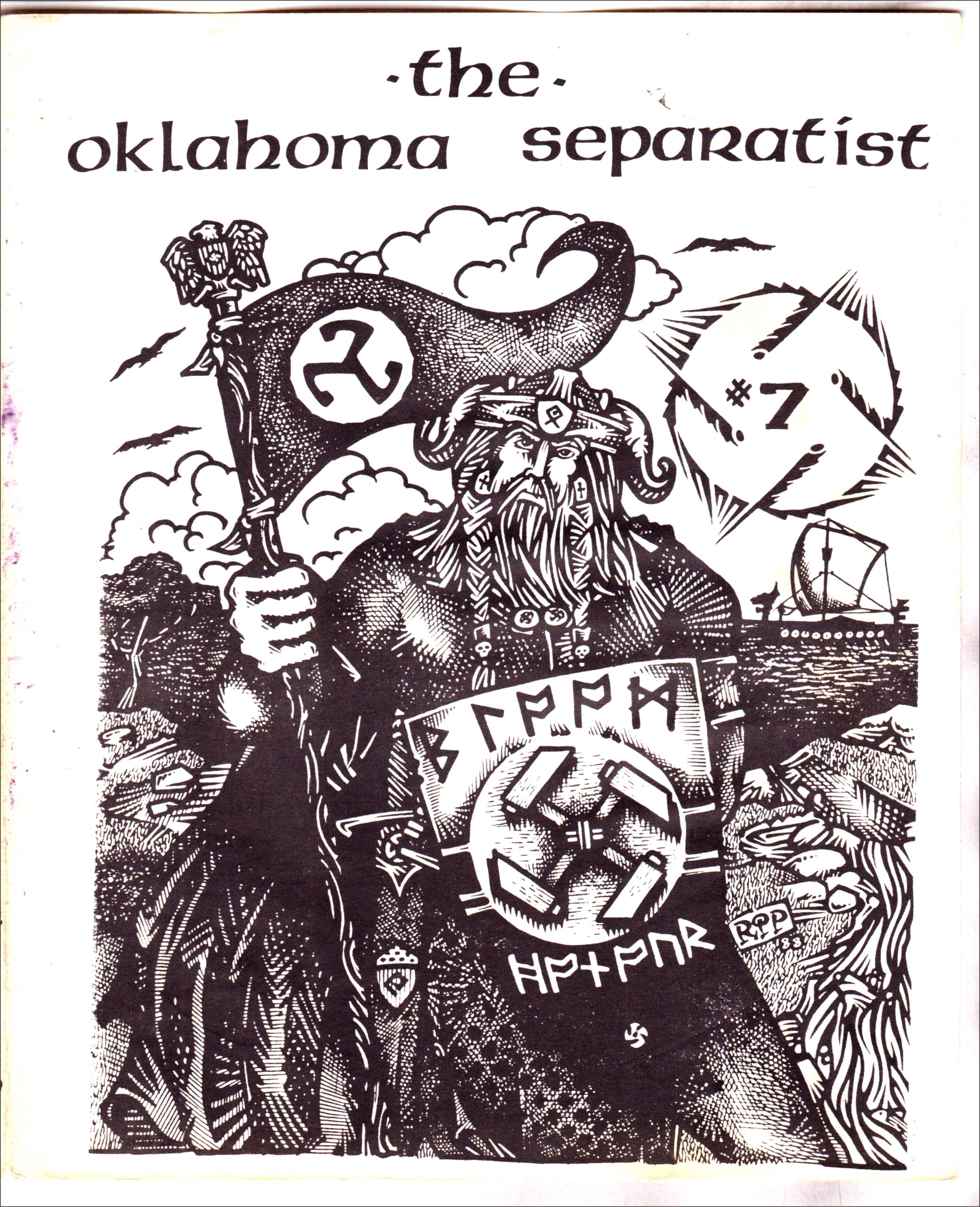

One American zine in particular exemplifies the truly amped up fixation on racist politics and violence that characterized the American skinhead zine genre: The Oklahoma Separatist, a publication dedicated to “racial unity,” published by the Oklahoma White Man’s Association. This was a grassroots collective of skinheads eager to build ties with the American Ku Klux Klan and Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance, amongst others.

First published in 1988, The Oklahoma Separatist features a variety of interviews with leaders in the white supremacist movement, reviews and news about upcoming concerts, and propaganda articles geared towards racial consciousness. These are all buttressed by calls to action, including letter-writing campaigns in support of incarcerated movement martyrs and reminders to continue to purchase memorabilia to fund the magazine and other racist causes.

∞

Rise of the Neo-Nazi E-Celeb

Jump ahead three decades, and hate propaganda, like many things, has moved online. Only a few hate zines persist in obscurity, and white supremacists now invest nearly all of their time and funds in the endless recruitment potential offered by the internet.

However, this is beginning to prove complicated for aficionados of hate speech and genocidal ideologies to exploit the very largest digital platforms. In the wake of the attempted siege of the American Capitol building, all of the major social media outfits started enforcing their community standards more stringently, freely banning accounts deemed as abusive. This purge has, predictably, prompted a mass exodus of white nationalists who seek both a community of belonging and a digital ecosphere where they can promote it, most of all a (highly digital) generation of teens and early twenties —sound familiar? This time around, the underground society has staked itself in intentionally alternative social media hubs such as Gab, Voat, and Parler. Of course, the most popular site for today’s hateful youths is, without a doubt, the flagship encrypted messaging app Telegram.

Telegram and similar alternatives claim offer coveted terrain for “free speech,” though only particular kinds of speech tend to happen there. And, as was recognized by the far-right fanzines of the recent past, there is a unique strategic power in a growing social club. Anyone at the vanguard of white nationalist ship in the 21st century will tell you: Telegram and its ilk are precious tools to strengthen their cause, unmatched by other media.

Telegram and similar alternatives claim offer coveted terrain for “free speech,” though only particular kinds of speech tend to happen there. And, as was recognized by the far-right fanzines of the recent past, there is a unique strategic power in a growing social club. Anyone at the vanguard of white nationalist ship in the 21st century will tell you: Telegram and its ilk are precious tools to strengthen their cause, unmatched by other media.

Indeed, a cursory scroll through public Telegram reveals a host of channels dedicated to white supremacist causes and memes, affiliations readily identifiable through such references as “14/88” (a numerical code for eminent racist publisher David Lane’s so-called “14 Words,” and the alphanumeric code “88” for “HH,” or “Heil Hitler”). These chat rooms provide disturbing portraits of an extraordinarily vibrant and thriving transnational Neo-Nazi subculture.

Perhaps the most bizarre such Telegram phenomenon is that of the racist cult e-celebrity. Innumerable channels orbit around this subset of influencers, who stream themselves hurling racist, antisemitic, and homophobic abuse at unsuspecting people on the other end of video chat randomizers like Omegle and ChatRoulette.

It’s an eerie ritual. These stars usually dress up in costumes, ranging from the skull masks popularized by the terrorist group Atomwaffen to mass media-inspired costumes, like Batman’s the Joker. Fans cheer on these self-styled vigilantes as they tear through a series of new and horrified chat partners. These performances, in turn, are typically uploaded to the alt video site Bitchute for their widely dispersed sympathizers to study and share.

Racist e-celeb culture is, in many ways, a far cry from the technology of the simple skinzine. But they share some key underlying functions. First, by encouraging its membership to constantly expand its highly aestheticized, highly insular iconography, producing paratext upon paratext. As such, this obsessive fringe subculture nearly guarantees its own survival. Just as readers and writers of racist punk zines enthusiastically produced new works mythologizing white power bands, symbols, talking points and Klan leaders, Telegram devotees elaborate on the work of their sadistic heroes without even being asked to. In fan channels running parallel to the home streams of these e-celebs, users extol and extend the new subculture of white supremacist ideology that much more with every coded chat, harrowing gif, or patch purchase. They spread hate with a complexity and pace that the editors of Blood and Honour could hardly have imagined.

They also glorify and gamify the process of so-called “radicalization.” Like hate in print, online white supremacy pushers relish the art of plausible deniability, stretching the limits of publicly acceptable speech via memes and inside humour. Soon after landing in a Telegram chat for the first time, a curious young man may find himself in pretty deep. In ceaseless posts and chats, peers applaud and reward each other for being the most extreme, a never-ending process of proving oneself which always requires that more harm be done. The victims of this hate race could be anyone — a traumatized student found on Omegle, a father targeted at a mosque shooting, even one of these unsuspecting Telegrammers themselves, whose peers suddenly turn against him as they have many others. What was that about shock troops?

The whole thing barrels forward, the chaotic momentum of race war accelerationism. It’s a grim recruitment project, one that seems to be working well, and at a rapid clip. That is, working so long as it lasts. During the first few months of 2021, several key Telegram personalities suddenly ceased broadcasting. The reasons soon hit the newswire: they’d been arrested for weapons, conspiracy, and plots of violence. Indeed, the heightened attention from law enforcement seems to have caused many of the biggest names in racist Telegram streaming to curtail their internet activities for a while, if not for good.

But those fan-run chat channels they’ve spawned carry on, even thrive, in the absence of their leaders. There will always be someone ready to paste the face of their political enemies on memes — or on mock “Wanted” posters — in an effort to affirm status with the in-group, even if that group is reprehensible. In that sense, examinations of a white supremacist movement must be premised on more than their mastery over any media tools. Going deeper means asking who is doing the dirty work, and why. It’s usually the little guy.

∞

For Spring Canzine 2021, BP Editor Jonathan Valelly interviewed Dr. Rogers for a further understanding of propaganda theory, the influence of skinhead puppeteer Tom Metzger, military infiltration, Telegram, zine affinities and more. Click below to watch!

Dr. Amanda Rogers is an internationally recognized expert on global media, political violence, and social movements. Her work has appeared in The Intercept, Al Jazeera, The New York Times, The Walrus, VICE, and on BBC. Rogers is a Century Foundation fellow and visiting assistant professor of Middle Eastern Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. She is currently writing a book about the white supremacist movement’s strategic infiltration of law enforcement and the military. Find her on Twitter @MsEntropy