Indie publishers are suddenly seeing the value of documenting punk history. Ian Gormely investigates why authors and first-wave punks are finally getting their opportunity to make sense of “a period with no previous narrative.”

Twelve years ago, Chris Walter submitted a manuscript to Canadian publishing house ECW Press. The novel, Punk Rules OK, told the story of Meatboy, a punk rocker who discovers a bag full of cash in a park and the men desperate to get it back. In writing the book — his second — Walter drew from his experiences as a lifelong fan of the genre, an interest that most prominently manifested itself via his internationally distributed Winnipeg punk zine Pages of Rage in the 1980s.

Months later he finally received a reply from ECW literary editor Michael Holmes, himself a punk lifer who still calls the Misfits his favourite band. “Christ! Coming to a firm decision on this has been difficult,” he wrote after praising the book. “I get, at best, to do two works of fiction with ECW a year — worse, some years I get to do only a single title. Having to decide which title has become terribly difficult. Sometimes I actually have to pass on a book that I’m quite enamored with. This is one of those times.”

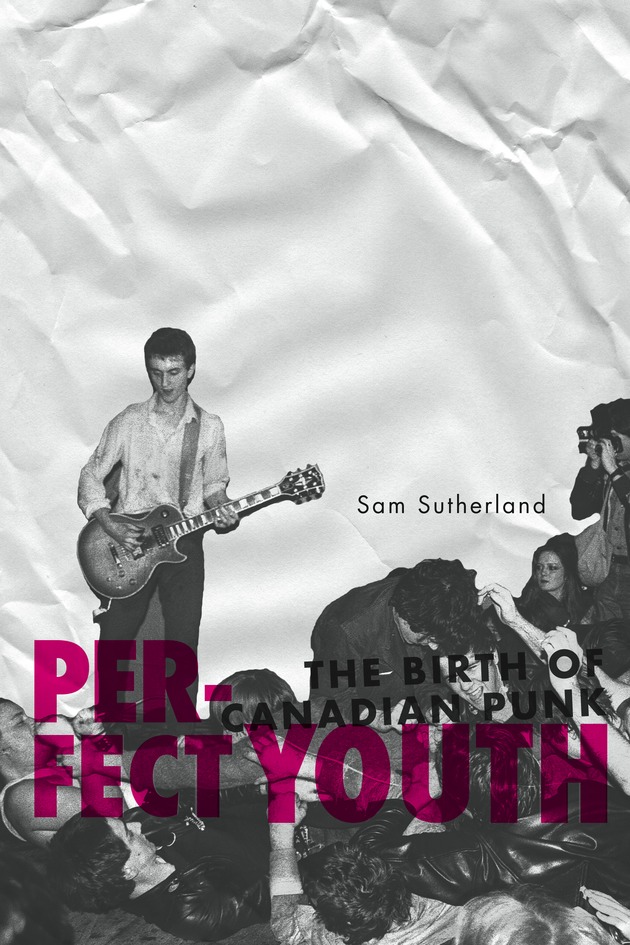

“He just didn’t think he’d be able to sell it,” says Walter today. Fast-forward a dozen years and ECW now includes three books about the early years of Canadian punk rock on its roster: Don Pyle’s photo diary Trouble at the Camera Club, Liz Worth’s southern Ontario punk-rock survey Treat Me Like Dirt (which features Pyle on the cover) and Sam Sutherland’s cross-Canada survey Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk.

Add to that Invisible Publishing’s band bio of long-running Victoria duo NoMeansNo: Going Nowhere by Halifax writer Mark Black, Jennifer Morton’s bio on Toronto’s Bunchofuckinggoofs and Walter’s self-published trio of band bios on Personality Crisis, Dayglo Abortions and most recently SNFU, and it looks as if the first wave of Canadian punk rock is finally getting its due — something that seemed unfathomable a decade ago.

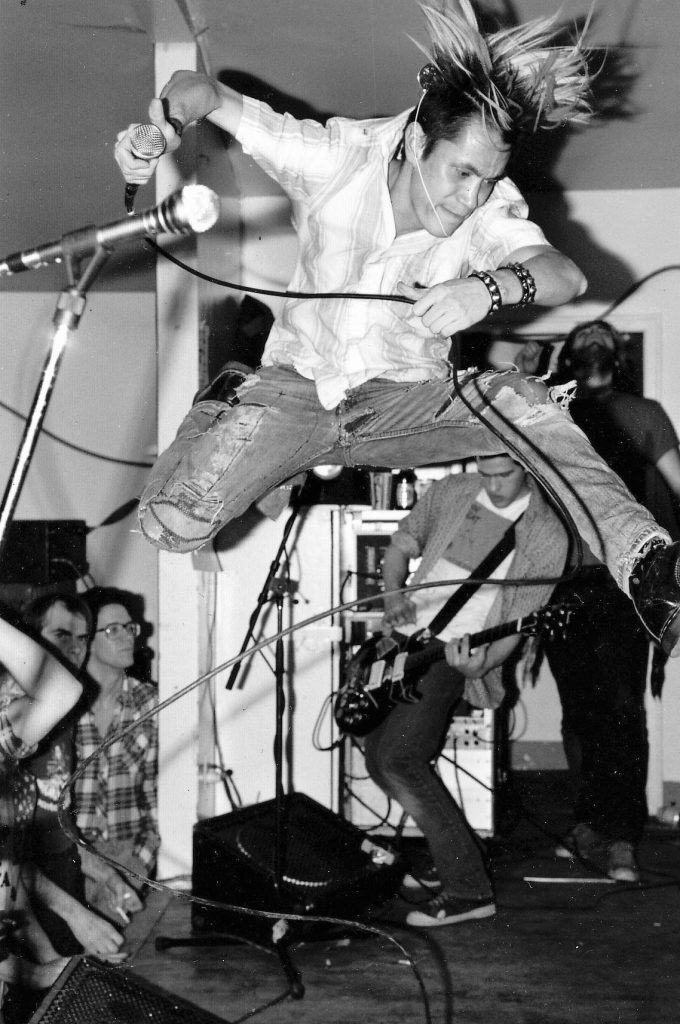

SNFU in Europe 2009, with Chi Pig as the only original member. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Denis Nowoselski and Chris Walter.

“Punk has been mainstream for a decade and a half or two now,” says Walter, on the phone from his home in East Vancouver. “All the small presses now realize they can shift some units with punk rock.” Yet it took years for the mainstreaming of punk to take hold in the publishing industry. Two decades after “the year that punk broke,” writers still had to fight to have these stories told.

***

Canada’s first wave of punk bands — a period roughly delineated as the mid-to late ‘70s up to the mid-’80s — was a scene defined heavily by geography. In reality, few bands trekked outside of their hometowns. “These scenes were poorly documented and fairly disconnected,” says Sam Sutherland. Some, like D.O.A., Teenage Head and The Viletones, managed to make their mark internationally. But dozens of bands barely managed to cobble together a seven-inch or demo tape before splitting up. Others, like Winnipeg’s Personality Crisis or Toronto’s Bunchoffuckinggoofs, simply disappeared.

It’s curious that the fans spearheading the current explosion of books — which effectively triples the number published on the subject — are in their late-20s and early 30s. As many of Canada’s most fevered local punk bands hit their peak, most of these writers hadn’t even been born yet. These writers came to the genre in the ’90s, after punk’s post-Nirvana and Green Day acceptance in the mainstream. But punk remembers its own history, says ECW’s Michael Holmes. “It’s an art form that inspires people to follow a trajectory through its own past.” For writers like Black, Worth and Sutherland, the joy comes from fulfilling their own curiosities about the bands and the music and tracing together some sort of narrative. In doing so, they’ve drawn lines and made connections through pieces of local and national music history in a way that hasn’t been done before. The first wave of Canadian punk, “was quickly becoming the final frontier of punk journalism,” says Sutherland. “There’s this hole… there’s a natural inclination to fill in that knowledge for yourself and then that can become a bigger project that you want to share.”

By the early 2000s, the people involved in the first wave had matured and gained enough perspective that some began to document their own experiences. D.O.A.’s Joey “Shithead” Keithley and the former frontman of Calgary’s Hot Nasties, Warren Kinsella (now a political strategist for the federal Liberal party), both put out memoirs, along with the Modernettes’ John Armstrong, aka Buck Cherry, whose Guilty Of Everything is currently in the process of being turned into a movie. Along with fictionalized versions of the Vancouver and Toronto scenes published in the ‘90s (Michael Turner’s Hard Core Logo, its subsequent film adaptation and Daniel Jones’ 1978), these books helped plant the seeds for the current spate of books.

The internet — specifically blogs specializing in long out-of-print punk records, demos and bootlegs — also created a gateway to the era for younger generations, leading to a renewed interest in the classics. “If it wasn’t The Diodes, if it wasn’t DOA, it was scouring the internet trying to find someone who has posted this rehearsal tape from The Normals,” Sutherland says, who also credits the possibilities of digital distribution and online research for the concurrent explosion of books on punk.

Chi Pig (Brent Belke in background) at Spartan Men’s Club 1985 by Pierre Robberecht. Photo supplied by Chris Walter.

Despite all this resurgent interest in classic, regional Canadian punk music, the work of conceiving and writing these books would prove to be only part of the battle. The attitudes Walter encountered back in 2000 as he shopped around his punk manuscript — “It’s interesting and important, but we can’t sell it” — were still pervasive. “It was hard to convince the mainstream publishers that this part of our culture is an important thing,” says Holmes. In the end, as Walter discovered, self-publishing and small presses provided the warmest and most favourable results. Sutherland says small press publishers like ECW and Invisible better serve

these books, and work to ensure that the stories reach their target markets. “Random House exists to get good placement in Chapters,” he opines.

And even with a warm and supportive reception, this type of leap is a major risk for a small press, due to limited resources and (at the time) an unproven market. “A lot of people told me they didn’t see a market for Treat Me Like Dirt,” says Worth, recalling the slog to find a home for her book that started in 2006. The author figures she submitted her manuscript to between 30 and 40 small and medium-sized publishers in Canada, the US and the UK. She even tried to enlist the help of a literary agent in the hopes that they might be able to get her manuscript in front of someone at one of the larger publishing companies. Ultimately her most valuable connection was through one of her own interview subjects. Ralph Alfonso, former manager of both Toronto punks the Diodes and legendary Hogtown venue the Crash and Burn, figured heavily in the book and eventually stepped in to publish it via his Montreal-based record label Bongo Beat. “It was definitely an unconventional way of getting a book published,” says Worth.

Treat Me Like Dirt’s initial run of 500 copies ended up selling out in about a month. It was subsequently reprinted twice before ECW picked it up last year for a fourth printing. “There’s a lot of work that goes into publishing. But sometimes they miss the mark,” says Worth. “It’s the same as in the music industry where a lot of things happen organically in the underground and later on the industry catches up to it.” Like most cultural businesses in Canada, the publishing industry suffers from a scale-based economy. “The audience in Canada for different books is pretty small,” says David Caron, ECW’s co-publisher. “Generally if you can sell 5,000 copies of a book in Canada, you’re going to be on a best-seller list.”

Caron says to break even on a book like Sutherland’s Perfect Youth, ECW would have to sell about 1,500 copies. “We’d be really happy if we sold 2,000 copies,” he says. As a reprint, Treat Me Like Dirt’s break-even would be about 1,000 copies. “They have a business to run,” concedes Sutherland, who specifically targeted ECW for Perfect Youth. “It’s not the duty of the publisher to make sure kids have access to the history of The Nils.”

That being said, Treat Me Like Dirt’s success and the buzz surrounding Perfect Youth provide quantifiable proof to theauthors that they’re not alone in their curiosity and desire to fill in the blank spots of the punk past. “It was this huge fucking flag telling people that there was an absolute hunger for the history of these bands to become a part of our written history,” says Sutherland. “People’s perceptions shifted,” says Worth. “There is more interest than they thought and they were willing to actually invest in publishing more about it.”

***

Today, Walter says Holmes’ glowing rejection letter “really kept me going.” Punk Rules OK was eventually published by Burn Books, but he opted to release subsequent books — there are over 20 — independently, through his own Punk Books imprint. “I make more money this way,” he says. Small publishers like Burn offer authors a small advance on their royalties, but it’s not enough to live on. “Unless I was picked up by a big publisher, I wasn’t going to make any money. I’d have to take a real job and I didn’t want to do that.” Holmes reads hundreds of manuscripts a year, yet he still remembers Walter’s book and has followed his career ever since it landed on his desk. “Chris has really developed as a writer,” he says. “I would have published it if I’d had the ability to do more books.”

Like punk’s mid-’70s inception, the boom in books about Canada’s unruly musical past is the product of a confluence of events: OG punks with enough distance for reflection, 30-something fans who came of age in an era of mainstream acceptance eager to explore its more dangerous roots, and the ability the internet provides writers to dig up and connect previously disparate and forgotten corners of the genre’s past. In many respects, the move from scummy squats and dives to the nation’s bookshelves is an

inevitable one. Punk isn’t necessarily something that grows up, but its fans do. Their hair may be a little greyer, and their clothes more respectable, but the hunger for the music never wanes.

I think you better sharpen your pencil because you missed the point!