Racer Trash is dead, but its tire tracks remain streaked across the fringes of cinema.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic until late 2021, a collective of irreverent (and largely bored) film and music obsessives gathered to re-edit iconic movies, then catching a Twitch broadcast to see the strange results, like tuning into a ghost signal.

What started as a dozen people eventually ballooned out to a collective of around 50. By the end of their brief-but-prolific 18-month run, they made somewhere around 35 films – or something like films.

“Racer Trash was a social experiment, in a way,” says co-founder Ariel Gardner over the phone from his home in Los Angeles. “During those early days of the pandemic, it was like we were at summer camp together. We were just looking for anything to do, to do together. And I think that energy really drove us. Whoever wants to do this, come on and let’s have fun.

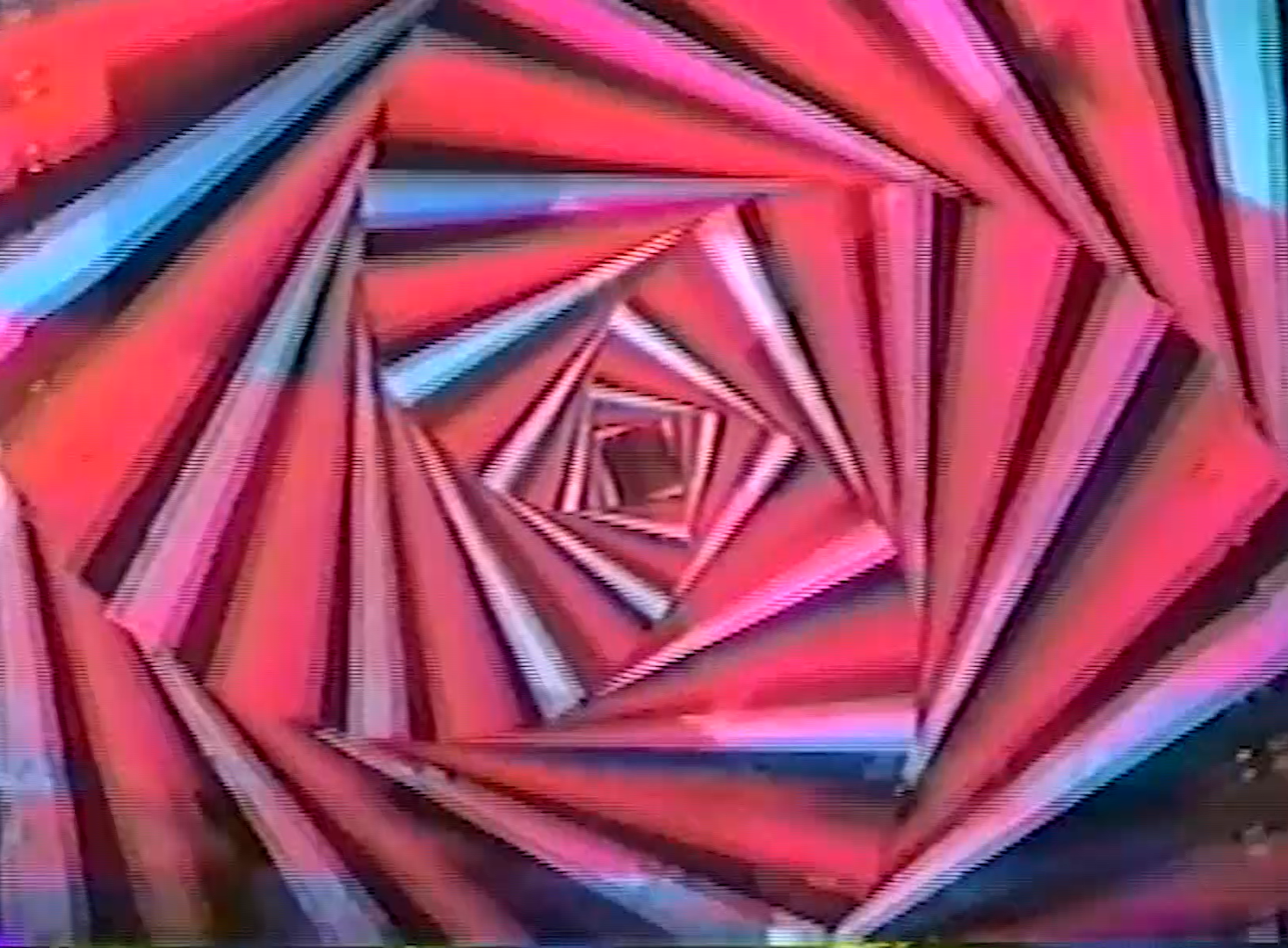

The initial screening was a “vaporwave cut” of the Wachowski’s 2008 cult flop Speed Racer, a synesthetic maximalist studio adaptation of the classic anime.

Racer Trash’s fever dream edits eventually grew well beyond the vaporwave aesthetic to its own language. There are VHS-damaged recuts of Baz Luhrman’s Romeo + Juliet, Daft Punk’s soundscape pinned to De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise or a Nine Inch Nails and You’ve Got Mail mashup called, what else, ‘You’ve Got Nails.

It’s hard to define. Something between a dream and watching a scrambled pay per view channel. Familiar scenes are chopped and skewed, recompiled with industrial or frantic electronic scores. Shots you’ve seen a thousand times might have new colours, patterns, textures. They might be spun 25 degrees. They might be intercut with pop culture free-associated from decades earlier or later. It’s trippy and funny. Spontaneous and surprising. Totally allergic to pretentious ideas of auteurship or film as an untouchable artifact.

“You play with a movie enough and you realize nothing is precious,” says Gardner, admitting he was at first intimidated to mess with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. “It’s like a Beatles record. You’ve heard it so many times that it goes in one ear and out the other, and all you do is wish you could hear those songs for the first time again. Racer Trash, at its heights and at its peaks, was achieving that.”

Racer Trash was born out of the particular “we’re all stuck at home” energy of the early pandemic that also gave rise to things like queer parties on Zoom, DJ battles on Instagram live, Animal Crossing house parties, Minecraft music festivals and endless games of Jackbox. That kind of cabin fever entertainment that showed the unquenchable need for connection through art, but was never built to last when in-person movies, sports, concerts and theatre returned.

The group did get to evolve into a physical space for a three-part series called Midnight Dankness that took place during, but not a participant of, the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival. One Racer Trash member is a trailer editor at the Royal Cinema where the screenings took place. There they unleashed videos like Dune 8421, a vibey edit of 1984 and the recent star-studded Dune, or a candy rave version of the original Candyman. There were also fake film festival bumpers and easter eggs for the local crowd.

Like the online events, it was as much about the community watching as it was about the visions onscreen. At The Royal Cinema there was a second screen displaying the live Twitch chat for people simultaneously watching from their computer. Many home viewers were speculating that a wild dance party must have broken out at The Royal, a bacchus overstimulated meltdown in the presence of The Babadook re-edited with ABBA hits. This was not the case, but why spoil the illusion.

“Each screening had enough of a guaranteed viewer base that it felt like preparing a meal for guests that were coming over,” says another Racer Trash spearheader, Alex Jacobs, in an email. “Even though the specific collective that was Racer Trash may have stopped racing, the waves haven’t really stopped.”

Since the end of the collective, Jacobs contributed to an edit of The Matrix called ‘The Wavetrix’ and one Mad Max: Fury Road collaboration with a Racer Trash member who goes by Grimy Ghost! Like Deadheads before them, a community of Racer Trash fans come together to stream movies every week for ‘Monday Movie Madness’ and in an “online gallery” called SegFest. They all show fingerprints of Racer Trash’s strange vision, especially as their community grows, with each taking the cinema circus in new directions.

Since the end of the collective, Jacobs contributed to an edit of The Matrix called ‘The Wavetrix’ and one Mad Max: Fury Road collaboration with a Racer Trash member who goes by Grimy Ghost! Like Deadheads before them, a community of Racer Trash fans come together to stream movies every week for ‘Monday Movie Madness’ and in an “online gallery” called SegFest. They all show fingerprints of Racer Trash’s strange vision, especially as their community grows, with each taking the cinema circus in new directions.

“Every now and then I’ll see something pop up that kind of feels like what we were doing,” says Gardner, “and then sometimes I’ll find out it was by one of us.”

Gardner’s new project is Dream Video Division, which he categorizes as a more intentional and controlled version of Racer Trash’s anything-goes anarchy. This recently manifested as a re-edit of Nosferatu called ‘Nosfera2’ that screened at the horror-focused Overlook Film Festival in New Orleans. He says that’s a logical outgrowth of Racer Trash: in-person event screenings that remain accessible to anyone still feeling a little cramped at home, whatever their circumstances may be.

“The idea has been thrown out of punk in the 70s and how that evolved into post-punk,” says Gardner. “With Racer Trash, the energy it thrived on was chaos, and now we’re trying to focus the chaos and develop it as an art form.”

Ultimately, Dream Video Division is just one iteration of Racer Trash. With so many cooks in the kitchen, everyone puts their own touch on the recipe. Is it about anti-capitalist critique? Fuck-everything nihilism? Virtual commune building? Translating remix culture from music to movies? Developing a new cinematic aesthetic? Let the chef decide.

“When we’re going back about Racer Trash and what we were, a question that kept popping up is: are we a band or are we a genre?” Gardner says. “Now, it feels like a genre.

Richard Trapunski is a Toronto-based writer and editor. Formerly the music editor of NOW Magazine, he now sends himself out to events and then critiques his own spelling and grammar.