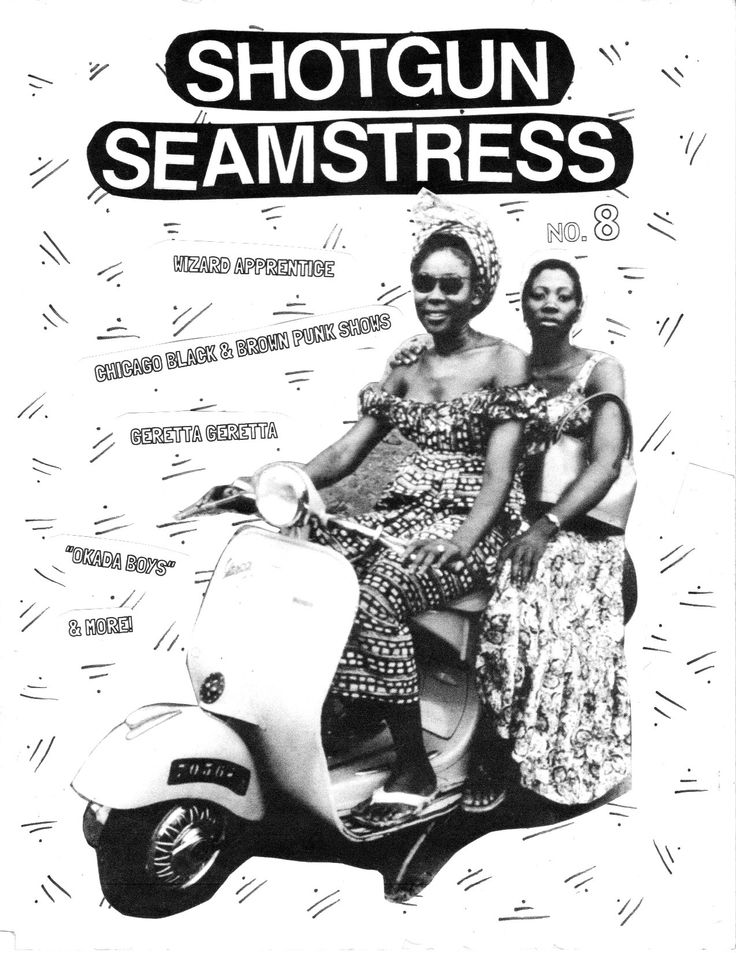

Cover from Shotgun Seamstress #8

Interview with Osa Atoe

by Alison Lang

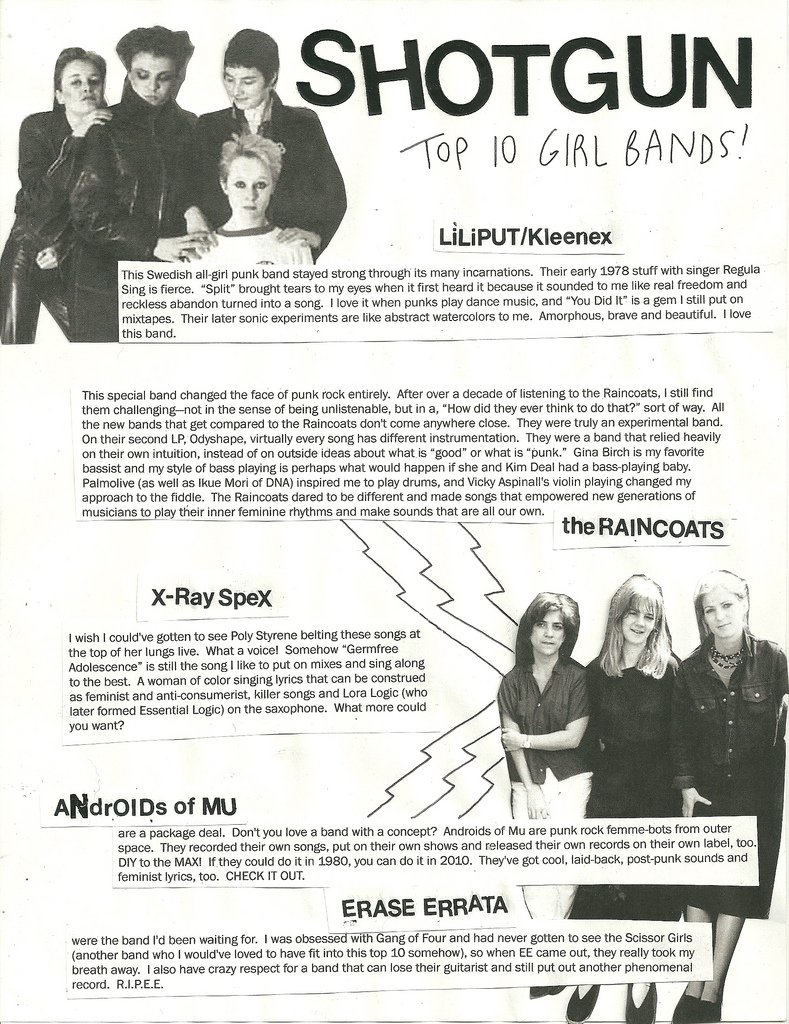

2006 was an exciting time for zine culture, especially with regards to the abundance of zines made by queer punks and punks of colour. Mimi Thy Ngyuen’s seminal text Evolution of a Race Riot was one of many zines that inspired a young black queer woman living in Portland to make a publication of her own. Osa Atoe’s Shotgun Seamstress is a fanzine first and foremost, focusing on black and/or queer punks, although Osa also branched out from that, with pieces on psychedelic rock musicians, performance artist Vaginal Crème Davis and a loving tribute to RuPaul’s past as a punk artist and performer. She also focused an entire issue (SS #6.5) on four Nigerian-American punk rock musicians. Through well-chosen collage artwork and incisive, knowledgeable and exuberant writing, Osa (who also spent many years in punk bands herself) made an indelible statement about black music and culture. She did this simply by covering the music and personalities she loved, always with an underlying commitment towards equality and a cogent understanding of identity politics. SS went on a brief hiatus in 2012 but Osa returned with SS #8 this past spring (hooray!).

Broken Pencil: You started Shotgun Seamstress nine years ago, when you were 26-27. You were also touring a lot with your band The New Bloods at this time. How’d you start lining up interviews?

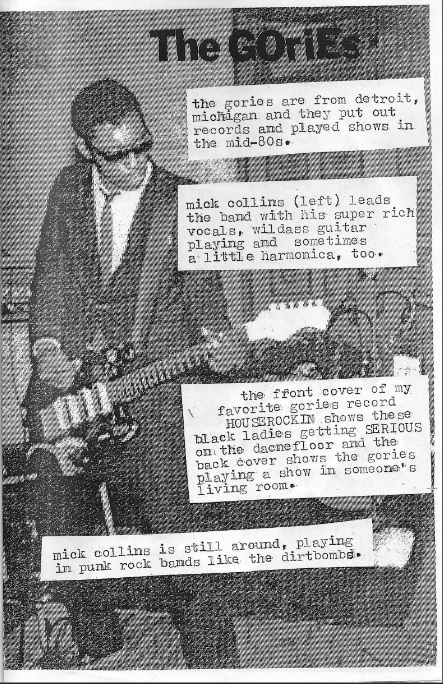

Osa Atoe: Touring and the zine went super hand in hand. I tabled the zine with my merch. I also got to meet people…some of the interviews I did, I could do because I was on tour. Meeting Mick Collins of the Gories was due to the fact that my band the New Bloods was playing a show in Detroit (he lives there). And I had a friend there who could connect us, so we were able to sit down and talk.

How did you feel the first time you interviewed someone?

The first people I interviewed were all my friends. My girlfriend at the time Adee Roberson and my friend Brontez (Purnell), who still makes music and art and dances in the Bay Area, in California. It felt really casual. It was a kinda cool way to start. It wasn’t premeditated – it felt obvious, like why not interview the people who are around me? Maybe that was a cool way to start off – I didn’t feel as nervous or intimidated people I didn’t know because I was able to get comfortable interviewing people I did know.

What was it like talking to Mick Collins?

It was so cool. It was one of the greatest interviews I ever did. It was fun and funny, a great conversation. His partner at the time was there — she stayed pretty silent, and Adee was there with me…it was like a comfortable conversation. Interviews can be awkward – I’m sure you know!

Oh yeah.

And that one wasn’t. It was rad. I love talking to older people. They have so much more to tell. They’ve been around longer. They have way more perspective, and they can tell you how things have changed over decades and time.

The first issue of SS feels really assured. How much pre-planning went into its creation?

I tend not to be an overthinker. I tend to think about things after the fact more than when I’m doing it. I don’t know. Not a lot was super premeditated. I had been reading a lot of zines, it came pretty naturally. I know I was young, but I was 26 – not 18. I had been in zine culture for a minute, I knew what zines looked like and were supposed to be like. I knew I wanted it to be more of a fanzine. I wanted to celebrate my identity instead of grieving for it.

When did you decide to take a break from zines?

After #6 came out, I was starting to feel like I was running out of stuff to say on the topic. And I think I was finding it a little confining, because when you think about it, punk is a really small world and within that, black punk is really tiny. I have never featured a band just because they’re black – I always featured bands and artists that I really truly loved. That’s not a lot to choose from! Even in the way I define punk, which is pretty broad compared to most people. I like tons of all white dude punk bands too. I like a lot of different things across the board. I felt at the time I didn’t have anything else to say on the topic.

I traveled to Nigeria, met new black punks and it took three years to rejuvenate, get reinspired and save up a new batch of black punks that I hadn’t written about before! Also the Black Lives Matter movement gave me things to talk about and think about. New things to feel, new ways to feel. When it arose as a movement, it made me think about how my zine fits into it. Every issue could be the last. It’s just another form of expression. These days I teach art after school and started a little pottery business. I don’t play music at all anymore, I’ve slowed down a lot on booking shows and attending them.

Can I ask why?

I’m 36, man! You know? I don’t go out as much as I used to, I only go to shows when I’m really excited about the bands, or they’re in a new space, I’m not in the mood to stand around, drink and watch my friend’s band play for like the millionth time. I love them, but I want to take months in between seeing them. I’m just not as social as I used to be, and I’m focused on other things.

How do you feel your identity as a punk manifests itself now that you’re an adult?

I still participate in punk culture – I still buy records, I just don’t go to every single show anymore. Now I go like once a month. It’s just who I am. It’s never gonna go away. I’m more than just punk, though. I have interests that exist outside punk. It’s too small. But it will always be a part of who I am. I’m in this community. All I know are these freaks, you know? I can’t just change. I’ve tried to do that in the past – I moved to Oakland, I was like “I’m not going to be a punk anymore! I’m tired of all these white people!” And then I hung out with all brown and black people like me, who were still freaks and queers. It’s really hard to escape at some point, even if you want to! I don’t understand how people just say I’m not a punk anymore and just leave it all behind.

Do you feel the process of zinemaking over the years – has that contributed to how you conduct your own dealings in the world – becoming a teacher, starting your own business? How have zines helped?

I actually teach zines! I have zines made by little kids, and that’s an awesome thing to share. But I also want to impart that punk mindset: it doesn’t have to be perfect, it doesn’t have to be fancy, and we don’t have to be super money-hungry. Obviously I want to get paid what I’m worth and make a living, but I’ve also worked for other potters and I see how they operate when it comes to business and selling their goods. I saw shit that I don’t agree with, as a person who wants to work for myself. The whole mentality is that things can be simple and also be good. You don’t have to wait for a point where you become “technically advanced” to get started. I’m still learning and I still feel confident enough to put my work out there. That DIY punk ethic and mentality really helps with that.

I’ve learned so much about kid culture. I think it’s cool. Especially as someone with radical politics, you wanna tell these kids about struggles, stories. There’s tons of radical kids books out there. I want them to know what I think is important. But I think it’s really rad for kids for share with me what they think is cool and important too.

Last December you wrote a blog post saying Shotgun Seamstress was a “feeble but conviction-filled attempt” to change mainstream conceptions of blackness. I thought there was a lot of humility in that statement. Now that your zinemaking is more sporadic, have you figured out other acts of resistance – as a black woman, as a feminist, as a queer woman – that work for you?

That’s a tough question because resistance can be defined in so many ways. I feel as I get older, especially in personal life, there’s a lot more pressure to conform. In my personal life I’m constantly resisting the norms that are expected of me as a woman. There’s that. I’m not an activist anymore, in the way that I don’t do a lot of community organizing like I used to. Mostly it’s about trying to connect art to activism wherever I can – using zines and books to support local organizations, having benefit shows is a huge part of that, raising money for women’s organizations, mostly just being an ally.

A lot of that comes from the fact that I’ve been a transient person, and therefore I don’t see myself based in any specific community. I approach New Orleans with a lot of humility. It’s a very old place, and people have been dealing with a lot of shit for their entire lives that I don’t understand. There’s no way that I would feel comfortable inserting myself as a major player in the activism that happens here. I see myself as a transplant ally – I see what’s going on here and I want to throw my support behind it, like those organizations that are most impacted by this town’s bullshit. I step to the sidelines. Mot of my work has been like that. Provide free childcare for radical organizations. I used to want to be out there like the Black Panthers, like front and centre! I wanted to be doing all that stuff, I also think there’s a lot of obstacles in that world — it was disillusioning to me. Then I was like – I have to be true to myself! I am an artist. And I should connect art to activism whenever possible.

You can order the Shotgun Seamstress zine collection through Mend My Dress Press over at mendmydress.com.