I’m willing to bet there’s an underground zine-esque scene in Iran. Call it a gut feeling. No, call it an Iranian gut feeling.

As someone of Persian ancestry, I’ve kept an eye out for Iranian zines since I joined Broken Pencil three years ago. Zines and resistance go hand in hand, so it’s easy to imagine that, under a government known for threatening civil liberties, Iranians are exchanging print-only literature in the streets. But the search is tricky — for starters, they’re probably not even called zines! — and so far, they have eluded me.

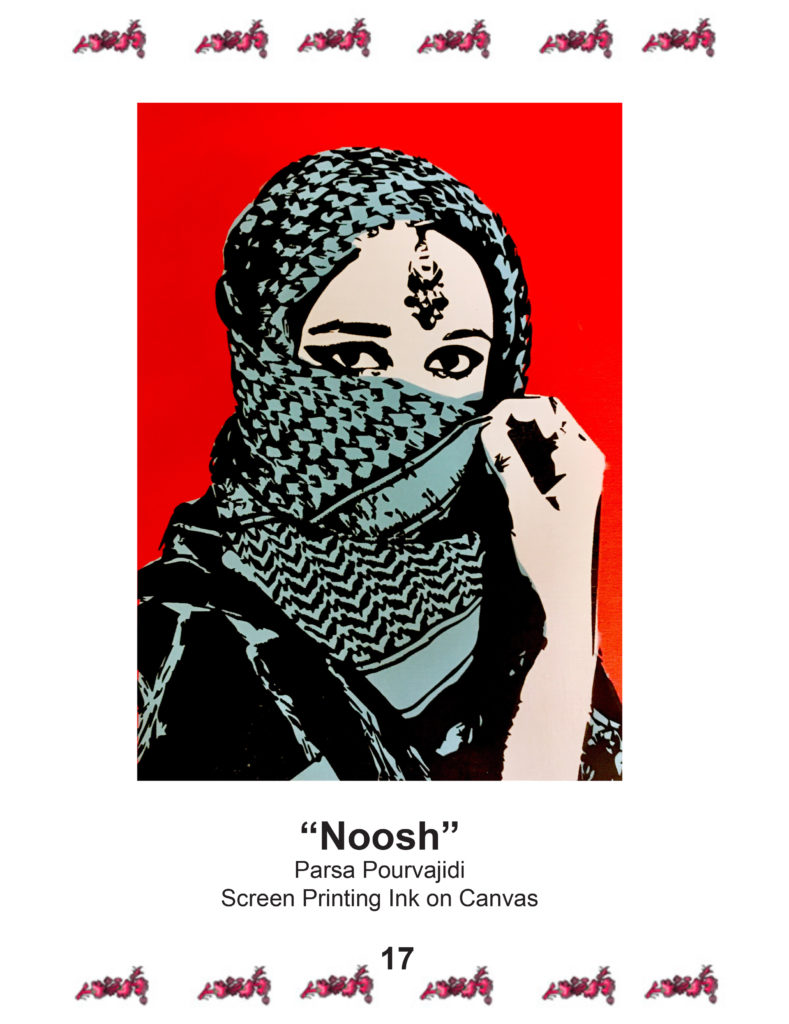

Then I came across Dooneh, a zine project by Donna Ghassemi, a 21-year-old senior at UCLA. Dooneh is a compilation zine with submissions by folks from the Iranian global diaspora, including contributors from the US, Canada, New Zealand, and the Netherlands.

I recently chatted with Ghassemi about the zine project, her relationship with the country and the tumultuous times we live in.

The conversation revived some reservations I have about writing about zines in Iran: if I were to find the Iranian zines I’ve imagined, would it be ethical to write about them? Zines are a tool of resistance to authoritative forces, but to fumble reporting on them would make us a vehicle of surveillance ourselves. Afterall, Iranian zinesters are the ones facing the risk — and no story seems worth compromising someone’s life.

What do you think? Tell us your thoughts on truly underground projects, or experiences where that’s been compromised. We will keep them anonymous and, if you request, confidential. Contact me at [email protected].

Anisa Rawhani: I’ve been wanting to talk to Iranian zinesters for a while, so I was so happy when I saw your zine. So tell me, are there others like us out there?

Donna Ghassemi: Ha! That’s part of the reason I started it. When I was in high school, I was pretty into zine culture. Last year, I got back into it, and I was looking around for a while, trying to find an Iranian zine I could potentially contribute to. I didn’t see any other people from the Iranian community dabbling in zines.

I don’t think a lot of people know how valued art, poetry and literature are within Iranian culture.

Yeah, I definitely agree with you. I wanted to keep that appreciation for the arts going with this zine.

Can you tell me about your personal connection to Iran?

My parents are both Iranian immigrants. My family’s been in California since the ’80s and I was born here. While I was in middle school, my parents decided they wanted to move back to Iran for a little while, so I spent my seventh, eighth and ninth grade in Tehran. They wanted me to get to know the culture a little bit more and my dad’s side of the family. So, I’ve been lucky enough to have experienced living in Iran and also the Iranian-American experience in America.

It’s not often that you hear about someone going back to Iran. Can you tell me a bit about the zine?

It’s not often that you hear about someone going back to Iran. Can you tell me a bit about the zine?

I was really shocked at the internationality of it. It was really cool to see how far it reached. I would love to print the upcoming issue and the current issue and spread that around. But for now, it’s just online, which I think is good, and it makes it more accessible to people.

Did you find any unifying themes in the submissions or was it more broad?

It was broad. I wanted it to be that way. I purposefully didn’t set a theme because I didn’t want people to feel like they’re limited. I might in the future do issues where there is a theme, but for now, I think I wanted it to be whatever people wanted it to be. It’s created to be for Persian people, by Persian people.

So it’s not just restricting Persian creators to solely creating content about Iran

Exactly. A lot of people were like, ‘Oh, I don’t know if I have any art relating to being Persian.’ And I was like, ‘That’s not the point.’ Because I don’t want people to feel like they’re limited to only art relating to our culture. While that is extremely cool, obviously there’s more to people and their lives than being Persian, so I want their art to reflect whatever it is they are.

Dooneh. Is that related to anar? (Dooneh means seed in Farsi. Anar means pomegranate.)

Yea, I just like the name Dooneh because I thought it was kind of cute and easy to say. But also in a larger sense, you can say that dooneh anar, it’s a small seed of a bigger fruit. Like each submission is a smaller seed of a bigger community that we are, that’s spread all across the world. They all come together and become this — this sounds so cliche — larger fruit.

I think that’s really beautiful. Iran has been through some tumultuous times, and has generally been in a pretty precarious state, but particularly right now after the assassination of Soleimani. I guess I’m curious about your thoughts. Personally, all my family is from Iran, but I’ve never been because we’re a Baha’i family and it’s very dangerous for us there. But I think I always thought I’d be able to visit the place where my biological body hails from. And now, I’m not so sure. There’s this threat on cultural sites, on art and on our history, and it feels like by the time I even get there — and this sounds very selfish — the Iran of our ancestors will be destroyed and no longer exist.

Jesus. I remember seeing (the threat on) the 52 cultural sites and it just made me sick to my stomach. Because that’s not an attack

on the government. That’s a direct attack on the country’s

culture and people. I remember seeing a thread on Twitter with a series of pictures of mosques and castles. There was one tweet, they said something about how there’s this certain shade of blue called Persian blue, because it’s used so much in Persian Islamic art. The phrase “Persian blue” really stuck with me. So my plans for the second issue, in light of recent events, is to focus in on Persian blue as an homage to the cultural sites that were threatened.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.