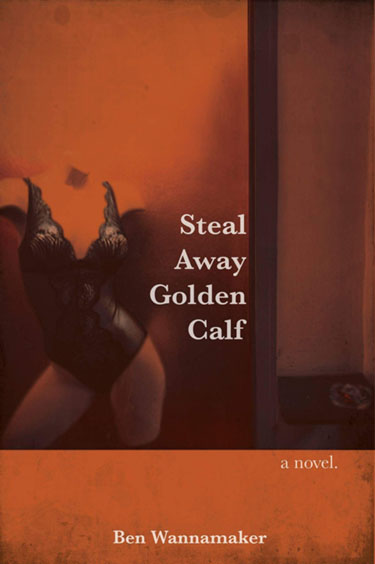

Steal Away Golden Calf

Ben Wannamaker, 156 pgs, One Of One Copyhouse, $9.99 (ebook price)

Publisher One of One Copyhouse, headed by Ben Wannamaker himself, lists six major works in the paratext to Steal Away Golden Calf, but he distinguishes this novel from the projects that came before it by referring to it as his “freshman novel.” It does, indeed, hold a special place among his other artistic activities — by parsing this dystopian drama and figuring out the structures at play in his imagined future, we are perhaps able to read backwards and view our society through Wannamaker’s skeptical eyes.

Unfortunately, this is where the narrative falls flat; Wannamaker’s interest in Foucault and societal power dynamics has led him to write a thought-experiment, the merit of which I leave to those who judge thought-experiments. As a piece of writing, Steal Away Golden Calf is marred by purple prose, broken syntax, and a frustrating tendency to lean on shock-value as a literary trope.

The novel follows Hammer through his young adult life in a dystopian Western society. At an early age, Hammer takes it upon himself to break every law he’s able to, daring the government to remove his limbs (the reigning punishment for any and all crimes) one by one until there is nothing left to remove and he’s immolated.

“By systematically removing my parts from existence,” Hammer claims, “it only proved to me … that I had truly and inevitably at one time existed.”

It’s around the time a limbless Hammer begins dating Anna (a little person whose breasts were lopped off because Hammer refused to testify in her favour) that we realize Wannamaker is telling this story with a straight face, and that he expects his reader to take it equally as seriously. If you are the kind of reader who’s able to make this leap, then perhaps Steal Away is for you.