As the Vector Game + Art Convergence 2014 festival comes to a close, I’m left with a sense of curiosity mostly piqued by the events of its final day.

Throughout the weekend’s events, a number of games have been on display in several Vector-hosted exhibits. Sunday’s events included a panel discussion among curators, game developers and artists on how these games are organized for events like Vector, and how curators can construct the best possible environment for the presentation of game based artworks.

Curators and creators alike have found interesting ways of approaching that presentation, including assembling arcade machines out of cardboard (which presented its own problems when it came to fire codes). Pulling it off, the panels agrees, can be especially important for the continued presence of these works.

“A lot of these games can’t exist as commercial works,” said Cindy Poremba, curator for game exhibits including Kokoromi, XYZ, and Joue le Jeu. “That would be ridiculous.”

The discussion touched on an interesting question about the nature of game based artworks and the concept of a singular industry they are supposedly tied to.

The discussion touched on an interesting question about the nature of game based artworks and the concept of a singular industry they are supposedly tied to.

A lot of games these days, one attendee noted, tend to be focused on local multiplayer-oriented gameplay. That is, games involving two or more players playing on a single screen, rather than on their own systems via the internet.

That trend, panelist Lee Tusman (Punk Arcade) pointed out, comes and goes. The medium is very fluid. No single format or style hangs on to its normalcy for too long. And experimentation can often be the driving force behind these changes.

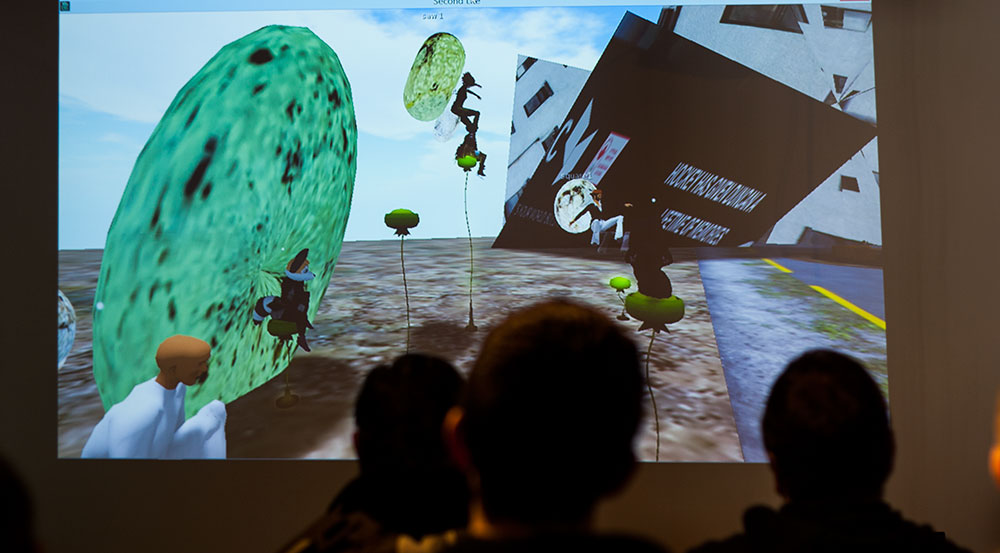

Earlier in the day, I attended a matinee performance by Avatar Orchestra Metaverse—international musicians and performers who use the virtual world of Second Life to forge musical experiences through various digital instruments.

Unfortunately, the performance was somewhat mired by technical issues primarily associated with network lag. The result was an avant-garde music ensemble unfortunately missing much of its instrumentation, and some other accompaniments appearing miscued or otherwise delayed.

“When it happens, it can even make the performance sound more interesting,” said AOM member Tina Pearson, who conducted the day’s performance.

“When it happens, it can even make the performance sound more interesting,” said AOM member Tina Pearson, who conducted the day’s performance.

Regardless, they all took the issue in great stride and emphasized the potential performances like AOM represent of the medium.

Technical issues aside, I admit, the performance was at a certain level of avant-garde production that wasn’t particularly accessible to my ears. The cacophony of glitchy noises, chiptune-like melodies and stock sound effects presented a strange and interesting audio canvas, but my expectations for these elements to converge into a surprising harmony were never really fulfilled.

And yet, I stood in that room fascinated by what I was experiencing, and Pearson’s point about the medium’s potential resonated in my mind even before she brought it up. What the performance, and indeed the entire festival demonstrated is that there are real spaces still up for creative exploration within the digital medium.

We live in a world where artists from Germany, Norway, Italy, Canada, USA and Sweden can all come together in a virtual world to create live musical performances using only virtual tools to a virtual audience. And that’s a hell of a thing.