“I’m going to have to ask you to open the trunk, son.”

“The trunk?”

“Pop the trunk and stay seated, please.” The officer turned his head away briefly, pulling at the sleeve of his uniform and pressing his chin into his shoulder. “Dispatch, patrol 332, got a vehicle matching the description for call 12-6. Over.” The radio replied with an indecipherable staccato voice wrapped in static.

Jonathan raced through a dozen scenarios in his mind and only a few of them, all far-fetched, ended well.

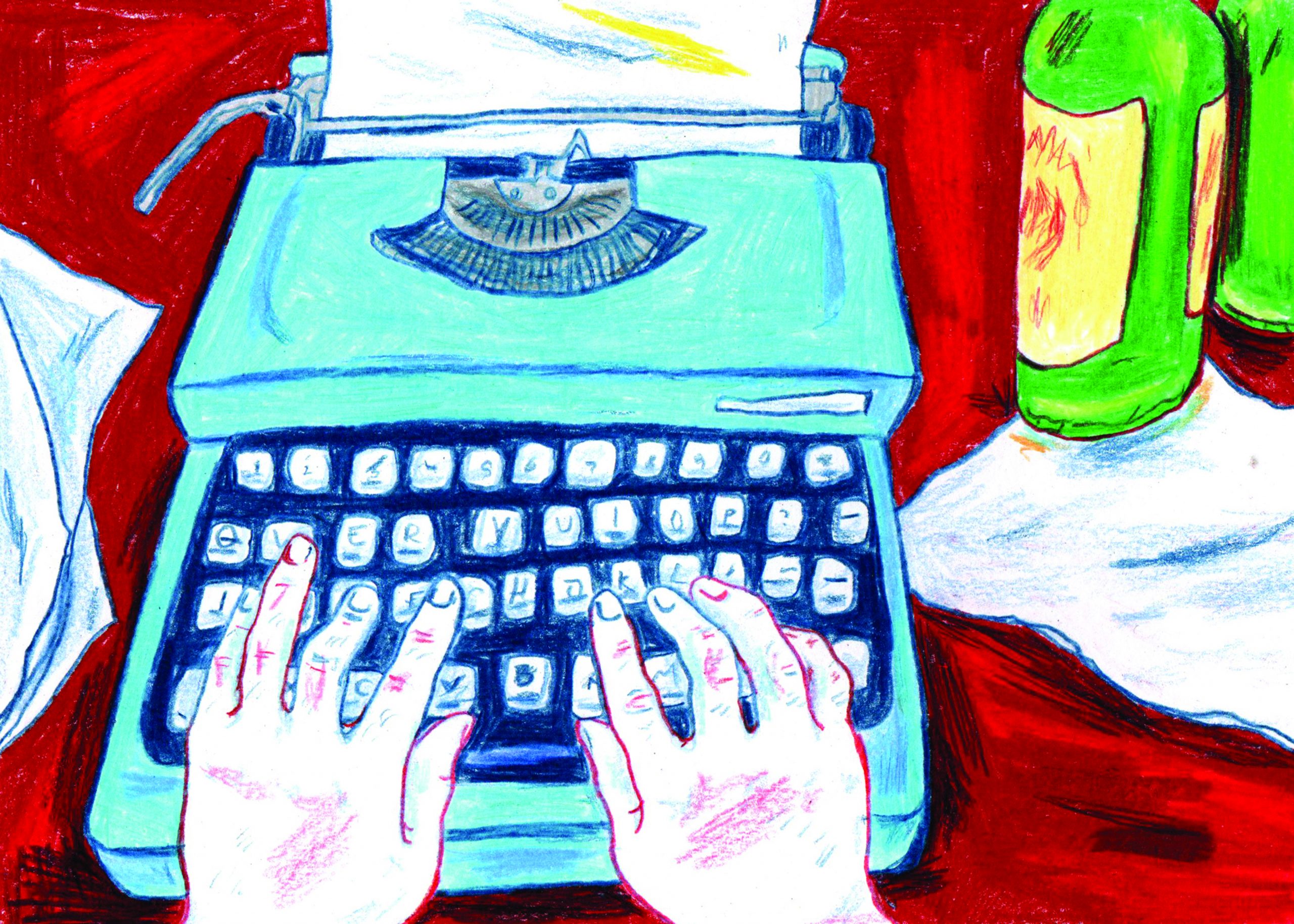

Whether they were looking for him or had mixed him up with somebody else was irrelevant. If the car matched a description they likely had probable cause to search it. But he wasn’t certain. The panic tightened around his heart. He thought to say, no, you can’t search my car, but didn’t want to make the situation worse by protesting. Realizing he was adding suspicion by taking too long to respond, he opened the trunk while hastily thinking up cover stories. The 1970s powder blue electric typewriter was in a black duffel bag jammed under the spare tire, but was too big to fully hide. He could pretend he didn’t know it was there, but that defence would fall apart after a few questions. He could say he was an antiques collector, which would maybe mitigate the sentence, but he’d still be found guilty of a crime. It felt like his life, a cauldron of gold smelted from expensive education and family connections that had just started being poured into a mold resembling his parents’, was spilling inside his gut. He closed his eyes and tried not to throw up as his organs burned. He heard the trunk slam shut and, opening his eyes, watched the pressed black uniform and shiny badge slowly moving closer in the Audi’s side mirror. Jonathan could see his licence and registration poking out from the officer’s open breast pocket.

“You go to Harvard, Jonathan?” The patrolman asked, returning the registration but keeping the licence.

“Yes. Yes, I do.”

“You got a sticker on your back windshield.” He observed, answering Jonathan’s unasked question. “So is this your car?”

“It is.” “You have a job, Jonathan?” “I’m a PhD student.” “How’d you get the car?”

“It was a gift. From my parents. When I got into the program. I can call them if you want.” It was a cool day for April but he was sweating, the heat starting in his forehead and radiating downwards. He felt his shirt starting to stick along his back. The cop withdrew from the window, straightened up, and looked down the street. He leaned his forearm against the roof of the car, squinting at something in the distance that Jonathan couldn’t see.

“Okay. You’re good to go,” he announced, handing back the licence. He knocked twice on the roof of the car, walked to the black-and-white cruiser without another word, and sped off.

Jonathan took a few deep breaths, pressed the ignition, and carefully steered away from the curb. He drove aimlessly for a while, constantly checking his rearview mirror, before pulling into a McDonald’s parking lot. He cut the engine, opened the door, and vomited onto the cracked pavement.

“What the fuck?” Brian nearly leapt from the small kitchen table when Jonathan finally entered the apartment, over forty-five minutes late. “Seriously, what the fuck? Where have you been? I almost took off.”

“Here,” he responded, placing the black bag carefully on the table. “I got pulled over. They searched the trunk. I could be in jail right now.”

Brian tried to calm down. He looked at Jonathan’s ashen face and skinny arms resting limply by his side, and knew anger wouldn’t accomplish anything. Instead, he opened the bag and looked at the typewriter.

“Nice color.” “Well, it works. Did you hear me? I got pulled over.” “So? You didn’t get caught. I take that as a sign. Stay positive.” “The cop looked right in the trunk. I don’t understand how he couldn’t have seen the thing.” “He probably did. And he let you go. That’s an even bigger sign.” “Let’s just do it, okay. Before I lose my nerve. You have the paper?”

Brian went to the tiny bedroom and re-emerged with a stack of about five hundred sheets of paper, all different sizes and colors because they’d been ripped from different books. The best were the big, thick pages from textbooks. A few of the sheets had writing on one side because they were copyright or title pages, but anything would work. He dropped the chaotic stack on the table next to the typewriter. The two men’s handwritten manifesto, prepared a couple of days earlier for distribution at the rally, rested on top. Brian resumed his seat and played with a lighter as Jonathan plugged the electric typewriter in.

“You took it apart, right?” “Of course I did. It’s legit. Totally original parts.” “I’d still prefer to be using a manual one.”

“Me too, but that would have taken too long to find. Trust me. This thing is over sixty-five years old. There’s no Bluetooth, no connectivity, nothing.”

“Okay. How fast can you type?” “It’ll only take a couple of hours to get all five hundred done.”

Brian went into the kitchen and pulled two beers from the fridge. He twisted the caps off and gave one to Jonathan.

“Brian, do you think this is worth the risk?”

“Yes.”

“We could go to jail. Or prison. And for what? We could hand these out tomorrow and nobody even reads them. Or cares.”

“That’s true. Or we could not do it. Then definitely nobody will read them.”

“Two white guys. This could be ironic at best. Or hypocritical.”

“Or paternalistic, or racist, or stereotypical. It could be a lot of things. But I believe it, you believe it, and something has to be done. Nothing could make things any worse.”

“Maybe it’s too blunt.”

“Oh, for sure. But this isn’t a Harvard debate, Jon. Nuance died a long time ago. You can’t balance a scale without putting the same amount of weight on the other side.”

“You can take weight off.”

“We’re doing the right thing. Let’s just get to work, okay?”

Jonathan took the handwritten note and typed it up. It was only one simple sentence, so it took no time at all to transcribe. The typeball rotated around as Jonathan struck the typewriter’s keys, slamming itself against the dried-out ribbon and then jumping over one space, eagerly awaiting the next letter with a sporadic, muted machine gun sound. With the first note completed as a template, Brian took the handwritten manifesto and burned it in the sink, transforming his tell-tale looping L’s and flattened A’s into anonymous ashes. The black and grey remnants mixed with water from the tap, turning into a viscous paste that washed easily down the drain.

“Another beer?” Brian called out, the job done.

“No thanks.” Jonathan declined, concentrating. The letters were coming out faint due to aged ink, and he worried the ribbon would go totally dry before he could finish. Photocopying wasn’t an option for a dozen reasons, so they had no choice but to continue and hope the message would be disseminated far enough. Whether it caught on or not was a different matter.

“This is the right thing,” Brian repeated, returning to the table. He leaned in, his green eyes disappearing into two shadowy craters created by the overhead light coming apart on his sharp brow and thick nose, widened by being broken several times. “It’s not perfect, but this is the right thing. It’s just an idea. A conversation, that’s all. It’s up to other people to decide if it goes too far or if it can be done or whatever. You and I, Jon, we’re just the ideas people.”

“This shouldn’t be coming from us,” he countered while still typing.

“Who better? Besides, nobody will know where it’s coming from. Okay, you keep typing. I’m going to go get some food.”

By the time Brian returned with a giant brown paper Burger King bag, Jonathan was nearly halfway done, the dirty, mangled papers divided into two piles on either side of the typewriter like an old-fashioned office desk with matching In and Out boxes. Brian unpacked the food, putting the wrapped burgers and overly salted fries onto two mismatched, chipped plates. The tiny square napkins were useless, having been carelessly tossed into the bag to soak up the food’s grease, so he tore off two sheets of paper towel. Seeing the plate, Jonathan said he wasn’t hungry, so Brian immediately ate the second Whopper. Carefully wiping his hands so as not to ruin his partner’s work, he grabbed the top sheet of paper, marveling at the bizarre, ancient typewriter font. It looked boxy, uptight, almost angry.

We propose a ban, to be automatically rescinded after four election cycles, on heterosexual, cisgender white men running for any national or state-level office. No exceptions.

“Do you think four elections is enough? Lots of damage to correct. That’s not a lot of time.”

“Well, I’ve already typed up like two hundred flyers.”

“You’re right. You’re right. Hey, you want your fries?”

“You just go ahead and eat the burger, but then you ask about the fries?” Jonathan smiled.

“I’m polite like that.”

Jonathan stopped his work and watched Brian as he squeezed an offensive amount of ketchup all over his plate. In earlier times they would have never met, but the protests were a tsunami missing only the city’s highest floors, an undertow grabbing at the limbs of people from every neighborhood and dragging them along until the wave broke downtown, depositing thousands of strangers to mix in the parks and on the streets. Jonathan had been immediately drawn to Brian only to be repulsed by his later confessions, but he’d slowly become convinced that Brian’s past absolutely wasn’t his present. He’d even used some of the money his parents had given him for school to pay for Brian to get the 1488 tattoo on his forearm removed, along with some others that were less obvious but equally unwanted.

“Sure, you can have th—”

There was a violent knock at the door and they both jumped. Jonathan stopped typing. Brian stood up quietly and tiptoed to the door, leaning forward to peer through the peephole. His left hand clenched into a fist against the wall as he continued looking into the hallway, his right motioning for Jonathan to hide everything.