We used to send mail, and there used to be an underground movement of artists who made mail art. Laura Trethewey tracks down the artists who made the postal system an integral part of their work to find out how mail art is faring in the age of the Internet.

In the mid ’90s, Rubberstampmadness –a periodical that at the time covered mail art and rubberstamping– was a 136-page glossy, colour magazine with classified ads, letters to the editor, a subscription base of 12,000 and retail sales of 8,000 copies. In 1992, publisher Michael Malan wrote, somewhat wishfully that “in the ’60s, it was drugs. In the ’70s, it was sex. In the ’80s, it was money, who knows, in the ’90s, it may be rubber.” But then came the Internet. Throughout the ’90s Rubberstampmadness’s focus shifted as less and less mail art filtered in and stamping, as a hobby unto itself, took off. Today, the mag runs the occasional issue on mail art, but with a limited print run of 7,000 copies. As the decade wound down, the WorldWide Web began to undermine the power of print and paper. A long running indie art tradition was faced with, if not extinction, then at the very least the daunting task of reinvention.

This once private process of making, sending and receiving mail art is now very much public and online. A quick Google search for “Mail Art” turns up hundreds of scanned images from Germany, Russia, India, almost anywhere in the world. This open and immediate exchange of ideas and artwork is very different from its scattered, hidden-in-plain-sight beginnings in the ’50s. Mail art emerged out of the influence and work of three geographically disparate art movements: the New York Correspondence School, the Nouveau Realistes in Europe and the Fluxus movement in Japan. It was a simple way to connect people all over a rapidly globalizing world, and a way to repurpose that ultimate symbol of technocratic triumphalism, the post office. Turn a postcard into a collage, mail a decorated envelope stuffed with all types of bricolage, and the act itself becomes art, prodding confused machines, awed postal workers and unsuspecting recipients into a different space, if only for a moment or two. As Mark Evard, the National Director of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers with over 20 years experience delivering mail, explains it: “I’ve seen decorated bottles, a coconut, a shell, empty Kraft Dinner boxes that have been decorated. Technically, we’re not supposed to be reading the mail, but normally when stuff like that comes through, people show it around to the other letter carriers in the aisle where they work.”

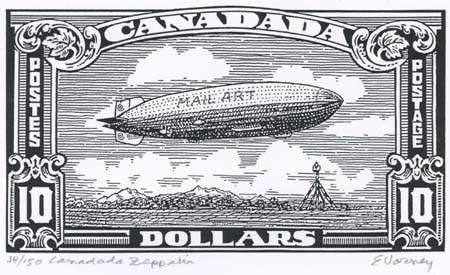

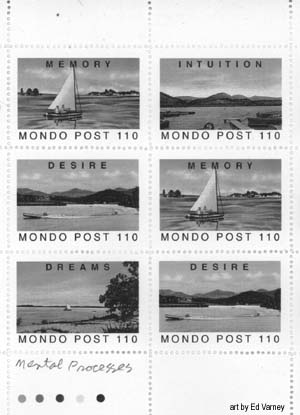

Some send around notebooks to be filled page-by-page with artwork or writing. Another popular objet d’art is a set of homemade stamps, more often called artistamps, a term coined by London, Ontario artist Michel Bidner in the ’80s. If there was such a thing as stated rules in mail art, they would include a few loose guidelines: Anyone can be a mail artist, all senders shall receive a response to a piece of sent art and pretty much anything can be considered mail art. In a time of cold war repression and obsessive commercialism, mail art challenged barriers and crossed borders. And it was just plain fun. As New York-based artist Sylvia Kleindinst puts it, during her adventures in mail art in the mid-’80s to mid-’90s: “I was writing to 40 or 50 people. My mailbox was always filled with these wonderful cards,”

But then came the Internet. “I think actually getting on the computer sort of killed mail art for me,” Kleindinst says. “I went into corresponding through Yahoo groups.” And other obstacles to the traditional practice of mail art arose around the dawn of the new millennium. “In the early ’70s, postage was six cents to anywhere in the world,” points out BC-based mail artist Ed Varney. “I could mail to 300 people for $18. Now, the same mailing would cost about $325 (assuming 100 Canadian, 100 USA and 100 international addresses — and weighing not over 30 grams). That’s a difference that can’t be ignored.”

With costs rising and new technologies threatening to usurp the viability of the practice, it’s hardly surprising that mail artists started to take their cues from the web. Dutch mail artist Ruud Janssen began experimenting with early Internet technology, such as the Bulletin Board System (BBS) in the mid-’80s. By 1990, he was ready to take his mail art community newsletter, the TAM-bulletin, online via BBS. (“Send anything that has to do with BRAINS,” reads a call-out in the inaugural electronic issue in November, 1990.)

Today, Janssen is one of the most prominent advocates of the online mail art community. He runs The International Union of Mail-Artists (IUOMA) with over a thousand members from all over world. The IUOMA operates as a sort of hyper-creative Facebook. There are updates of who’s friends with whom and photo albums of recent vacations, which are needless-to-say wholly unrelated to the practice of mail art. Yet the site is also a testament to how rich and sophisticated the online world of mail art has become. Many creative undertakings are coordinated through the IUOMA, such as a mail-art novel with over 30 artists contributing a different chapter. Its first seven chapters are already completed and online. The writing itself is entirely informed by the breakneck pace of the Internet with nods to month-old events, like Malcolm McLaren’s death, the iPad and the Icelandic volcano that shut down European airspace. Fittingly, the plot includes a mysterious mail art storyline, with a near nerdish similarity to fan fiction. There are also serious discussions conducted through IUOMA, some that even question the very foundation of mail art itself. One, posted by Janssen asks, “Do we need still [sic] snail-mail when we have forums like these?”

Many argue that we do. In fact, BC-based Ed Varney, one of Canada’s most well-known and active mail artists who has dutifully sent and received for close to 40 years, argues that relying on the Net may threaten the democratic underpinnings of mail art. “More and more the documentation is appearing on the Web, which sort of ignores the fact that many artists, particularly from third world countries, don’t have access to the Web,” he writes in an email. Clearly, those not on the web are shut out from adding to the mail-art novel, among countless other projects that have and will originate and be dispersed online. The Dutch artist Janssen tracks visitors to the bright orange IUOMA website, keeping an eye out for travelers from places like Africa or China. He says he does see the odd visitor, but so far he’s not received much from these countries. In May, Janssen began a blog called Chinese Mail-Art to actively pursue Chinese artists who might want to be found. So far, he’s had no success. “You first need an address,” he writes and mentions that at this point he’s planning to walk into Chinese restaurants and simply ask people whether anyone has contacts he can write to.

Perhaps the reason Janssen is so persistent in tracking down artists cut out of the loop by the Internet is because bringing unlikely people together is one of the notable accomplishments of this underground art movement. Romanian artist Iosif Kiraly writes in Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology: “In the ’80s, Mail Art was, for me, and many artists from communist countries, the only possibility to have a contact outside of our borders.” He makes this point concrete in his 1982 performance of a massive envelope holding several people, explaining that often in oppressed countries the only true part of you to escape is through the mail. American mail artist Kleindinst still corresponds with a Russian mail artist, who contacted her shortly after the Berlin Wall came down. They’ve been exchanging work for close to 20 years now, although she admits she was at first hesitant about corresponding with a Russian after so many years of Cold War propaganda.

Despite the drawbacks, for Janssen the Internet is less a threat to traditional mail art than an additional way to carry on the tradition. In what is already an art form based around communication, another way in which to connect can only strengthen the movement. “An artist shouldn’t be trapped in one medium,” he writes via email. “Communication in art is an essential factor. That is one of the essential points in mail art.”

Laura Trethewey gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council’s Writers’ Reserve Program.