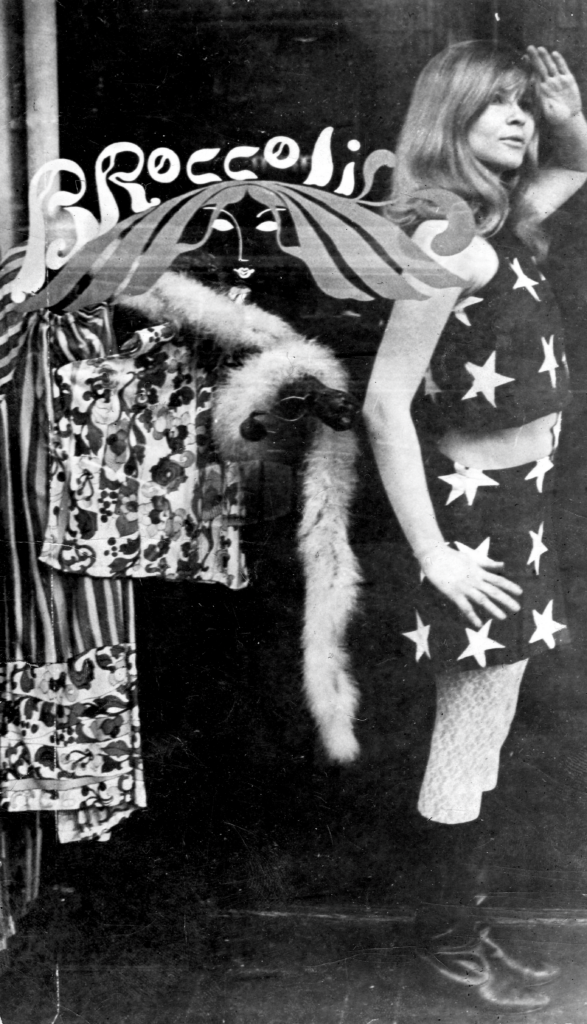

One thing to understand about Trina Robbins is that she wouldn’t want me to be writing this eulogy. Trina was many things, but the most enduring of them was embodying an act of creative resistance. That is, resistance not only against the tone and character of comics, with their permeating, masculine violence and exploitative sexuality both overt and subterranean, but against the overgrown boys who made them and the undergrown boys who read them.

One thing to understand about Trina Robbins is that she wouldn’t want me to be writing this eulogy. Trina was many things, but the most enduring of them was embodying an act of creative resistance. That is, resistance not only against the tone and character of comics, with their permeating, masculine violence and exploitative sexuality both overt and subterranean, but against the overgrown boys who made them and the undergrown boys who read them.

To read a Trina Robbins comic is to enter an alternate history: one in which the legions of women who entered the industry as writers, artists, and editors during the war years of the 1940s were never driven back out by media contractions, Kefauver persecutions, or the reactionary force of the patriarchy. Her comics spanned genres and subject matters with wild abandon, but it’s the sincerity of the work above all that shows through: a thoroughgoing, unapologetic embrace of her own art for what it was, in all its feminine and feminist imperfections.

And it’s the comics, in the end, that really do matter. It’s sometimes easy to lose sight of that, if only because Trina’s personality so frequently loomed as large as her work. Everyone who describes Robbins invariably lands on a circumlocution like “feisty,” and we might as well say it outright: Trina liked a good fight. There are vanishingly few players in the comics scene who don’t have a story with some spirited argument with Trina on one subject or another, though the delighted confrontationalism never dimmed her undeniable charisma. In her own way, she was as much a salesman for her alternate comics universe as Stan Lee was for his. Between the two, I know which one I’d rather live in.

But for all her politics, for all her personality, for all her controversy, there’s a sense of deliberate innocence that underlies the best and most enduring of Trina’s work. In a profile published in Kitchen Sink’s Comix Book, she said that her failure in art school was a result of her undimmed love for art that was blunt, honest, and totally devoid of refined taste. “It took me a good ten years to finally get back into comics,” she said, “to realize that I liked drawing comics, whether it was art or not, and to be able to finally stand up and publicly admit that I would rather have a Norman Rockwell than a Picasso.”

Everything about her art reached back to that earliest, nascent moment in her own childhood, and in the childhood of comics, when all things were possible: for art, for readers, for the place of women in the art form and in the society they depicted. We were invited in, and if we chose to stay — if we chose to live in that world, fictional as it was, and make it our own — Trina would be the last person in the world to stop us.

Zach Rabiroff is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. He has written on comics, prose books, music, TV, and film for the Comics Journal, Polygon.com, HITS Magazine, io9, Popverse, and elsewhere, and is a founding editor of Open Letters Review. His work appears sporadically, as the media economy allows it.