The rise of cycling as culture

by David Silverberg

It’s a bright Toronto day, perfect for a bike ride. In Queen’s Park, cycling enthusiasts are celebrating Bells on Bloor, a mini-festival of all things two-wheeled. In a quiet corner of the grassy area, three people from Clay and Paper Theatre are singing their ode to the bicycle, complete with posters of bikes navigating ugly traffic jams.

“Two wheels are better than four, it’s a fact you can’t ignore, sometimes less is more, yes, two wheels are better than four!” the young cyclists sing, ringing bells and sporting bike helmets. The song is part of the troupe’s “Bicycle Revolution Cantastoria.”

Whether they know it or not, these members of Clay and Paper Theatre are part of a larger movement of passionate cyclists promoting their cause through artistic projects. Or are they passionate indie artists drawn to the bicycle as an increasingly potent and accessible metaphor of change and possibility? After all, activism is only one spoke in the wheel. Across North America, theatre troupes, visual artists, filmmakers, graphic novelists, and zinesters are not only highlighting the importance of cycling lanes and enviro-friendliness, but also seeking to create dynamic works of art. A bike as a muse? Why not?

The bike is appealing as the subject of artistic works because it can be used as an instrument in novel ways, says Cat McLeod, one of the organizers behind Clay and Paper’s Cyclops, otherwise known as the Cycling Oriented Puppet Squad. Its bike-based theatre project places the bike as the central figure in a love story, while using it as a tool to discuss issues like overconsumption and pollution. The squad melds puppetry with biking in order to “enliven Toronto’s public spaces” and create thoughtful art in a medium that will appeal to adults or children. “And we want to encourage people to cycle in Toronto, which can be an intimidating and threatening place to cycle at first,” she adds.

On the other side of the country, another theatre group is blending biking with performance. Theatre SKAM in Victoria produced Bike Ride, a project that leads cyclists along a four-kilometer stretch of the Galloping Goose trail to witness various theatre pieces about the environment. Your bike seat is your seat for the show. The trees are your silent ushers. These playlets might involve canoe acrobatics on the water or actors dressed as beetles singing about turning BC’s forests into an “all-you-can-eat tree Happy Meal.”

But the bicycle isn’t just a multifaceted prop for political performance art. Its influence is more pervasive than that. Artists blending bike culture into their projects may be looking for a way to rebel against our car-focused streets, but they also seem to identify with the bike on a different level; as an inanimate reflection of their own self-sufficiency.

“The bike is a symbol of self-reliance and symbolizes our struggle for independence,” says Gabe Dominguez, co-founder of the Bicycle Music Festival. Based out of San Francisco, the BMF is a mobile fest where cyclists on special stationary bikes pump their legs so the bands can get electricity. It works by lifting the rear wheel in the air with strong kickstands, so that energy can be converted to electricity using generators. That energy is fed into a pedal power utility box, which smooths out the system’s jerky nature and makes it usable for the fest’s audio gear. At BMF, music lovers won’t hear the bands if they stop pedaling on the stationary bikes; the simple act of pedaling mushrooms into something much more integral to the listening experience, and the participants become willing batteries.

“We have values similar to the green movement’s,” says Dominguez. “Environmental sustainability, non-commodification of art, the power of community.” Here, Dominguez makes an interesting point: in an era of increasingly strident environmentalism, the bike, as a source of power both literal and symbolic, bridges the divide between activists and artists. It is at once a way to soothe guilty consciences and convey a message that everyone can agree on, regardless of political spectrum. The bicycle’s time as a cultural object is now, because of the way it can be repurposed to mean so many disparate things to so many disparate people.

Consider, for instance, Evalyn Parry’s one-woman show SPIN, recently staged at Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. Part play part concert and part song cycle, Parry takes us back to the 1890s and the oft-ignored story of the first female cyclists. A spoken-word portion of SPIN recalls the role of suffragettes and their passion for biking, as background bike bells and spoke-type instruments offer an appropriate soundtrack.

“Bikes tell us about courage,” says Parry. “It’s about resistance to change within the system. The bike as a metaphor can point to universal ideas about freedom in a complicated world.”

In reclaiming the bike as a feminist icon, Parry is following in the footsteps of early mid-’90s zines like C.U.N.T. (Chicks United for Non-Noxious Transportation), which merged boisterous in-your-face sexual politics with an almost fanatical zeal for cycling through comics, stories and simple exhortations like “Keep on cycling. You look awesome biker-chick and you know it.” As Evalyn Parry puts it, “Bikes have long been living in the counterculture, and it’s almost religious how cyclists congregate with each other and share their passions for all things related to cycling.”

If you’ve ever ridden in bike gatherings such as Critical Mass, you know what Parry means: cyclists have an almost rabid fascination with the actual structure of their ride, but also with the community it breeds. Whenever a fellow cyclist dies in an accident for instance — such as the death of Toronto courier Darcy Allan Sheppard in 2009 — rallies and vigils remind observers that the biking community is a close-knit family.

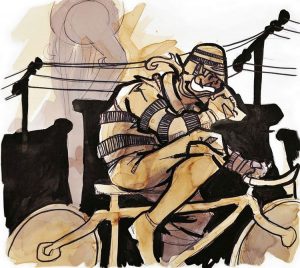

In 2010, Kenk: a Graphic Portrait divided that tight family. An unconventional graphic novel made up of documentary film footage photocopied and scratched with a razor, the book about notorious Toronto bike-thief/bike shop owner Igor Kenk drew praise from critics and outrage from cyclists who felt the book glorified the man who stole so many of their bikes. Both revered and reviled by cyclists, Kenk (the man) simultaneously represents a deep passion for cycling and a disrespect for the people whose bikes he stole. However, when the book came out, its artistry as well as its analysis of what Kenk represented beyond “bike thief” drew praise. In this, the bike is a conflicting symbol of consumerism and gentrification and freedom. Kenk’s methods, and in particular his ability to get away with selling stolen bikes for more than a decade, showed a consumer side of the biking community that didn’t question where the merchandise was coming from, but was simply happy to be getting things cheap. The work, by mulitmedia publishing team Pop Sandbox and writer Richard Poplak, takes various artistic forms: the journalistic graphic novel, interactive online excerpts from the book that feature video footage (made in collaboration with the Canadian Film Centre’s Media Lab) and a forthcoming documentary film.

Le Cyc is another example of a multimedia project inspired by cycling. Mixing a graphic novel with bike opera sounds like a messy idea, but somehow the Ontarians behind Le Cyc made it work. Now available on DVD, the live performance of the show features the story of a bike-powered world gone wrong under the iron bike-gloved fist of a malevolent dictator. Musicians play the score while singers narrate and play various characters. All the while, projections of scenes play above the musicians, a total of 380 paintings to illustrate the surreal action.

Le Cyc isn’t a statement about cycling per se, says Dave Willekes, one of the artists behind the project. “It’s a statement about taking advantage of working people.” Le Cyc might not be preaching to the audience about cycling’s utility or reclaiming urban space, but it’s still a far cry from Kenk, which explores and perhaps glorifies the seedier side of a biking subculture that includes dealers, substance abusers and scammers in its midst.

If there’s a critique to be made of the cultural explosion of bike-themed creative action, it’s to be found in the Kenk vs Cyc debate. Not everyone involved in the bike subculture is an altruistic card-carrying member of the Greens. Not all stories involving the bike have a happy ending. For many, a bike isn’t a symbol of middle-class clean living, it’s evidence that they can’t afford what they really want and might really need: a car. Bike art, with a few exceptions, so far tends to preach to the converted, promulgating preachy panaceas while avoiding harsher realities.

So, is bike culture the equivalent of expensive organic cuisine flown to Canada for the benefit of assuaging the guilt of the privileged few? That, I’d argue, is far too dismissive an assessment. The movement is genuine, the enthusiasm is real. Bike culture practices what it preaches and is far more likely to inspire positive change than it is to dissuade us from cycling to work. Who, after all, can resist the infectious enthusiasm of Vancouver songwriter Shera Kelly’s “Bicycle Commuters Anthem,” a celebration of Vancouver’s bike-friendly culture? Then there’s Toronto rapper Abdominal’s ode to cycling, “Pedal Pusher,” and the Sprockettes, a “synchronized mini-bike dance troupe” out of Portland. New York’s Bicycle Film Festival has screened more than 380 films all related to cycling culture over the last two years. The film fest has grown to such an extent that the festival tours to over 20 cities around the world and organizers have added an art show to complement the screenings.

For too long, argues UK-based writer Rob Penn, author of It’s All About the Bike: the Pursuit of Happiness on Two Wheels, bikes were written out of our history. Late 20th century histories of human transport focus on the car and the airplane, ignoring the influence the bicycle had on everyday life for centuries before the widespread availability of the combustion engine. “Our ancestors thought the bicycle one of their greatest inventions, up there with the printing press, the electric motor, the telephone, penicillin and the World Wide Web,” he says.

For Penn, it’s high time the bike skidded back into the public consciousness. “It’s indicative of how the bicycle is being valued again, and of how it’s moved back to the centre of public consciousness in the developed countries,” says Penn. “I know a few people who have bicycles on their walls, as objects of art. Ten years ago, they kept quiet about this. They boast about it now.”

Today’s merger of artistic visions and cycling culture echoes what the world’s first cycling magazine, Le Vélocipède Illustré, concluded in an editorial in 1869: “The steel horse fills a gap in modern life, it is an answer not only to its needs, but also to its aspirations… It’s quite certainly here to stay.”

David Silverberg gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council’s Writers’ Reserve Program.