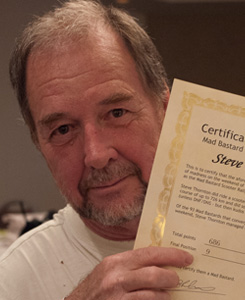

By Steve Thornton

I’m not crazy, but the Voices try to make me that way. I’ll be having a conversation with myself and they’ll cluster around my head like a sudden dowmackle, I mean, a murder of crows, crying “Hullaballoo!” and “Whoop-de-doo!” and cawing and clacking and flapping their black wings, and it gets so distracting that I have to write down what I’m trying to tell myself so that I can see the words, because I can’t hear them anymore with all that racket.

Sometimes it gets weird, though. Sometimes when I’m writing a conversation with myself the pencil will go skittering off the page and land in a corner, all by itself. Once I thought I saw it start to move. It lay there under the window that I can’t look through, and then it grew legs like a brakador . . . a mantis, I mean, and it walked for a little while and then it grew dandelion wings—or, no, dragonfly wings—and it flew back to me and landed in my hand. But I knew that wasn’t true. That would have been a hallucination, so I knew that I had just got up and walked over there without looking at the window and bent over and picked it up and got back into my seat, and just dreamed that it flew like a gwilodryne, I mean, a dragonfly.

I spend a lot of time in this room. I go out now and then, but just to the Macs store for some Gummy Bears, and I like the guy there. Pirgeet or Pajan or something. I can’t remember it so I just call him “Sir,” and he calls me “Sir,” and it’s all very civilized. He’ll say, Good morning, Sir, and I’ll say, Good evening, Sir. It’s a lovely day. And then I’ll buy my Gummies. One day when the Voices came, I ran into the Macs, even though I’d never been in there before. The Voices didn’t follow me, so I knew I would be safe there. I was not safe anywhere else, not even at home, the Voices would follow me everywhere else.

I used to go other places, but that was before. I remember going to the park, or the skating rink, playing throw-the-ball or bang-the-puck with kids. One afternoon I was going to pack up and go home for lunch. My mom used to make me peanut butter graplavics. I mean sandwiches. And she’d sit there and stare at me like I was doing some kind of miracle just by eating. How are you feeling? she’d ask. Are you having a good day?

Anyway, I told my friend I had to leave, and in a wink his mother was all over me, hissing like a bear. Not hissing, but . . . whatever. Brackadeaking. Her voice was low and wavery and it swirled around me and I had to run. When I got home my mom was mad at me for not playing with the kids and then she started to cry and said, “I don’t know what to do with you.”

I didn’t go to the park anymore. Since I got kicked out of school and they wouldn’t let me join the Boys Club again because my pants were sticky, I started hanging out in my bedroom and reading. I’d read the wallpaper and the little stories in the patterns on my linoleum floor. Those stories never had a good ending, they’d just change from some kid looking for his lost friend to a toilet with teeth that tried to eat me.

You spend too much time alone, my mom would say. You’re sixteen and you don’t even have friends. I’m scared, I would say in my mind. I was trying to think of what to say out loud when the Voices started yelling at me that first time. You are death! they shouted. I’d look out the window to get away from them and they would say, Look out there and you will see how you die! I looked out the window and saw a big truck, and the Voices said, Jump! Hurry! So I had to stop looking out the window.

Since Mom died I don’t get peanut butter sandwiches anymore, so I have to go out even if my death is there. I put my head down and run to the Macs and buy a radicle . . . I mean, a Gummy Bear, because I discovered that when I chew them I don’t hear the Voices so loud, even outside, they are still there, but they whisper. Dying is easy, they hiss. Living is hard. I wrote a letter to the Gummy Bear company once telling them about the properties of their Bears because I thought they could make a lot of money and maybe they’d start sending someone over with bags of Gummy Bears and maybe a hamburger. I didn’t have a stamp, though. So I didn’t get a hamburger that night or any Gummy Bears and I had to listen, listen, all night long to the yelling Voices. I get used to being hungry but I don’t get used to listening. It’s better to be hungry than to have your arms torn off by a black thing with red flowers, I mean, fur, in its eyes.

My pencil is almost gone. My mom used to give me a new pencil when I wore the old one down to a stub, but she can’t now, because she flew down the stairs. We were going out to the playground and I was mad at her. When we got to the landing before that long flight of practicles . . . steps, I mean . . . she just flew down and landed on her head. When the parking meter came . . . when the policeman came, he looked at me like he wanted to hit me, but then I went to a hospital so I could get used to not having a mom anymore and they were nice. When the Voices came and I had to scream the nurse came and rubbed my back and they got quiet. Nobody rubs my back now. I try but my arms don’t go that way. So that’s why I need the Gummy Bears.

Today I looked out the window. I didn’t know I was going to do it but the Voices were loud and I was thinking about my mom and I didn’t have the strength to resist. I saw it, though, and I wasn’t afraid of it anymore. I had no Gummy Bears and I wasn’t even hungry. I went outside and started walking toward the street where trucks rush by like zizzleborgs . . . killers, I mean. Before I got to the street I saw the Macs and I went in for one more Gummy Bear so it would be quiet when I did it. I said, Good evening, Sir, and he said, How are you, Sir? I said, I wore out my pencil, and he looked at me. He gave me a Gummy Bear and didn’t charge me for it because he knew I didn’t have any monkeys . . . or . . . whatever. I said thank you and goodbye and I walked back out into the noise and suddenly, just like that, it was silent. Not quiet like whispers, but silent.

I looked at the trucks coming with their big headlights and no sound, and I put my head down and started to go into them and their death silence and then there was one sound. “Sir, wait!” Something grabbed me from behind and pulled me back to the sidewalk and suddenly I heard horns and tires and someone yelling and I turned around and it was that Mr. Parjeet. “You forgot your change,” he said, and he handed me my change. I took it and held it close and went back to my apartment, and I sat and looked out the window and thought of Mr. Parjeet giving me change and I opened my hand and looked at it, invisible, like my heart, and I gazed at my change and wondered how Mr. Parjeet knew what I needed. He must know something special, I thought. I’ll go out and have a talk with him. So I put down my tiny pencil and looked for my socks, and then I walked downstairs and through the daylight and opened the door at the Macs, but then I saw something. I saw my mom sailing into the air off the landing and I saw my angry hands thrust out behind her back, and then I knew that she had not wanted to leave me. So I closed the door behind me and went into the Macs and said, “Good evening, Mr. Parjeet!”