graphic by Gord Hill

AKÌ.

In Anishinabemowin, “Akì” is the name we give to the Earth, to the soil, to the land underneath our feet. In our creation story, we are taught that Akì is our mother and that our heartbeat is synchronized with hers. From an early age, I was told that no matter how stuck I felt, Akì would provide for me, so long as I took only what I needed. As Anishinabeg, this was our way of life: Akì provided just enough; in turn, we used as much as we needed, making sure to waste nothing. Akì was to be respected and cared for — and when our journeys in this world were over, our bodies were to go back to her. Our territory — the small bit of Akì that the Anishinabeg were entrusted with — was so vital to our way of life that it went beyond physical hunting grounds and summer encampments. Our land was woven into our ceremonies, our cosmologies, the way we governed our own people and, like a mirror, the land was reflected in our own language.

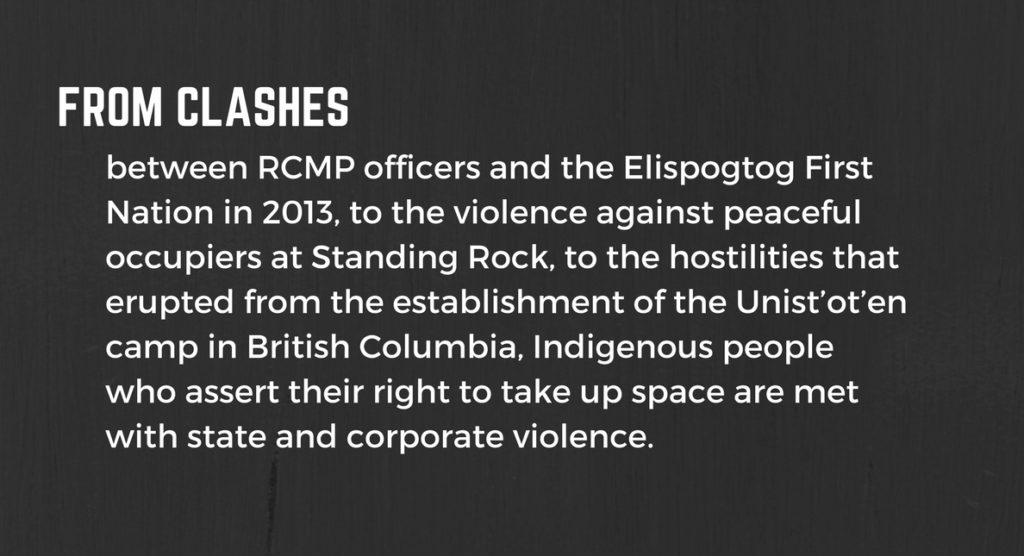

We are bound to Akì through mutual protection, yet at many direct-action camps and blockades across Turtle Island, it is common to see Indigenous land defenders treated as violent nuisances (*see sidebar). At the Standing Rock encampment opposing the Dakota Access Pipeline, despite being founded a symbol of peace and ceremony, Indigenous land protectors were brutally, but maybe unsurprisingly met with massive state and corporate violence. However, what was perhaps unexpected was the way in which this resistance inspired artists and creators to shape this modern trauma into a path of resurgence.

At the height of the Standing Rock standoffs, Ojibway artist Isaac Murdoch’s “Thunderbird Woman” emerged as the symbol of water defence. Murdoch’s grassroots arts initiative, the Onaman Collective, base their works on traditional teachings, tying into language revitalization and the resurgence of traditional cultural practices.

At the height of the Standing Rock standoffs, Ojibway artist Isaac Murdoch’s “Thunderbird Woman” emerged as the symbol of water defence. Murdoch’s grassroots arts initiative, the Onaman Collective, base their works on traditional teachings, tying into language revitalization and the resurgence of traditional cultural practices.

So the Thunderbird Woman is a fitting icon. The image is the outline of a woman, with two feathers in her hair, and two large wings instead of arms. In the centre of her chest is a red heart, contrasting against the white background and black painted details of the piece. In Anishinaabe tradition, the thunderbird is a figure of strength and protection. This spirit being is the guardian of the heavens. It beats its wings to cause thunder, and protects Anishinaabe from the horned serpent that guards the area beneath the ground (This explains another key image that has emerged: the large black snake used to describe oil pipelines). The image of a thunderbird and a woman together showcases the sacred role of women in communities. As givers of life, women have a powerful relationship with Nibì (water), Akì, and children. Thunderbird Woman honours how Indigenous women are born with a duty to protect their nations.

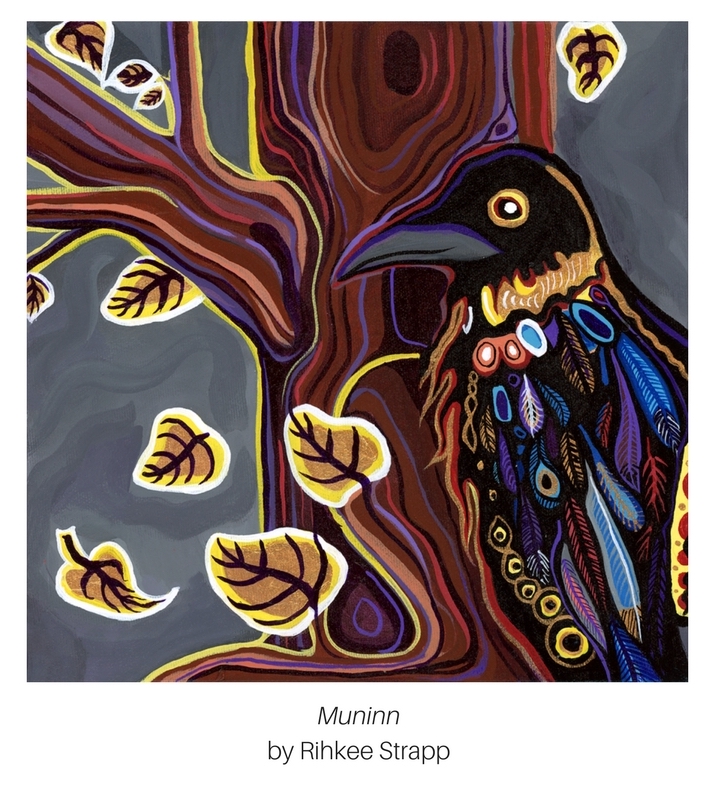

Before his death, Louis Riel stated that his people would sleep for 100 years and, when they awaken, it will be the artists that give them back their spirit. Artists like Rihkee Strap, a Two-Spirit mixed and Métis visual artist based out of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, find their work guided by this prophecy. Strap is dedicated to promoting and supporting other Indigenous artists beyond their personal art.

A habitual collaborator, Strap is often guided by ceremonies, visions, and dreams of other community members. Throughout their creative process while working with the Bawating Water Protectors (BWP), they worked alongside community elders, the Anishinabek Nation, and the Onaman Collective. One instance of collaboration with BWP involved erecting a teepee and building a sacred fire in the parking lot of their local MP’s office. During this reoccupation of space, Strap helped to facilitate the creation of four buffalo masks, which were used to protect the identities of the individuals that were there to show support. Throughout this process, the artists and organizers relied on advice from local elders, the Anishinabek Nation, and the Onaman Collective for their organizing and communications.

Strap’s method of creation is not meant to be resistance, per se. Instead, it is a means of resurgence. “[It] feels like a sacred obligation,” they reflected.

However, Strap is not so quick to call pieces like Thunderbird Woman and other visual representations of Indigenous teachings “art.” They look at the way elders rely on images for clarity in their teachings, and how they use gestures as descriptive language, as a shared mode that predates the Western concept of “art.”

“The ‘arts’ themselves are so steeped in settler individuality, processes, and systems that I often wonder how effective it is,” they explained. “This kind of work does not come together without community.”

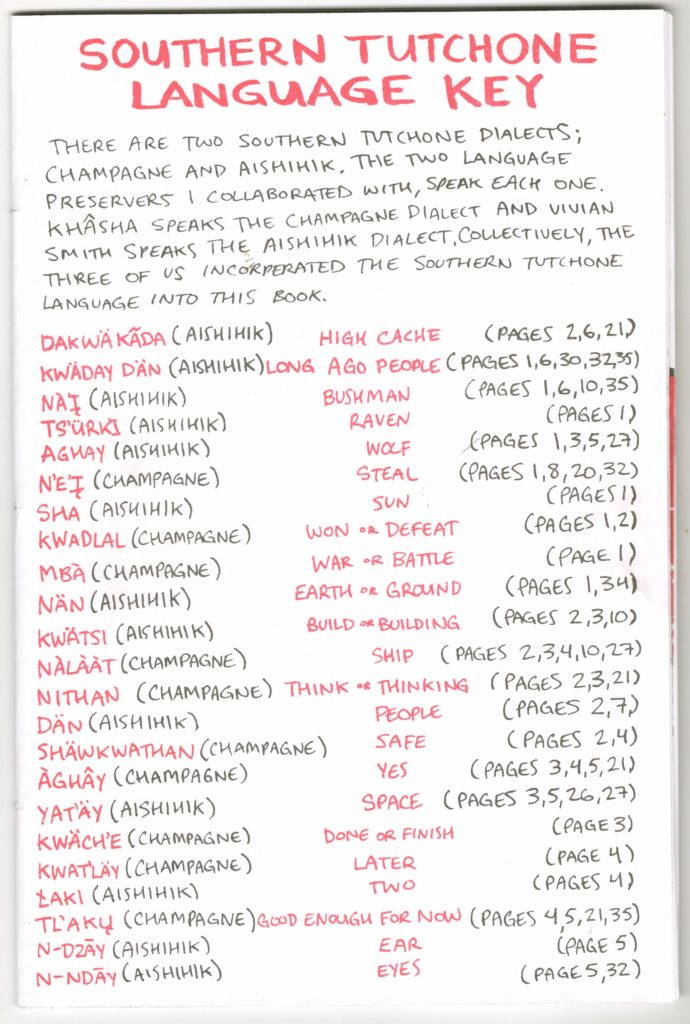

Collaboration with knowledge holders is also a crucial tool for other Indigenous creators responding to these issues. Cole Pauls is a Tahltan First Nations comic artist and illustrator who is best known for his comic series Dakwäkãda Warriors. The comic follows Ts’ür’i and Aghay, two Native space cadets that set out to defend the Earth from a cyborg sasquatch and an evil pioneer. Pauls combines traditional aesthetics with science fiction, placing Indigenous characters within a space they are rarely seen occupying. While working on his comic, Pauls teamed up with two language preservers who helped him translate his work into Southern Tuchtone. In this way, the comics become a tool for facilitating important conversations on land defence, and the resurgence of the Southern Tutchone language.

Still, why is it that artists with a focus on community and resistance are labelled “radical” in Canada? For Cole Pauls, witnessing the land being demolished for mining, fracking, and other forms of resource extraction is “an extension of colonization and assimilation.” Government and corporate encroachment on traditional Indigenous territories constitute a direct attack on Indigenous nationhood. Yet “reconciliation” continues to be a buzzword used by government officials and settler Canadians to wash over this violence.

“[It] starts with respecting our land and our people,” according to Pauls. Indeed, mending the severely strained relationship between Canada and Indigenous people can only happen once the government and privately-owned corporations begin acknowledging the jurisdiction Indigenous people have over their territories.

Gord Hill, a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation, finds his art rooted in anarchist beliefs. His comic The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book from Arsenal Pulp Press depicts various stories of Indigenous resistance to European colonization of the Americas. One story Hill portrays is the clash between the Kanien’kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke and the people of Oka in Quebec in 1990. The clash began when the town of Oka decided it wanted to build a golf course over traditional Kanehsatà:kehró: nonterritory. When the project was opposed by the people of the Mohawk settlement, they were met with racist violence at the hands of their settler neighbours. The people of Kanehsatà:ke were labelled a nuisance for halting a project that was meant to strip them of their traditional territory to appease settler capitalist greed.

“Maintaining traditional culture, including art, is an important part of decolonization,” reflects Hill. For this reason, Hill’s use of comic arts to tell these becomes an active form of resistance.

Many settlers neglect to acknowledge that, like our “art,” our “protests” can be more than just that. They can be a form of ceremony. They can be assertions of jurisdiction over our traditional territories, reclaiming spaces that have been stolen from us.

Indigenous folks are born with resilience in our blood, our bones, our breath. From an early age, we are brought up in a state that refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of our existence. Instead, we walk through your stolen territory as a living, breathing form of resistance. For Indigenous artists, sharing our stories of resilience, working collaboratively, and centering tradition transforms the narrative from one of loss to one of strength. Reoccupying our territories through direct action, through art, is not radical — it is, in fact, necessary for our survival. And it is our duty to ourselves, our communities, and to Akì.