“CULTURALLY DEAF PEOPLE don’t see deafness as a detriment — why would they, when there is a large, rich, vibrant culture with an accepting community around it?” writes Kerri Radley in the first issue of her zine, Deafula.

Radley, who lives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has been making zines since she discovered them in the late 90s as a teen. “I found a copy of Girls Guide to Taking over the World [edited by Karen Green and Tristan Taormino] (in the mall!) and was so inspired by it that I decided to do my own,” she says.

In 2010, Radley started Deafula, a perzine about growing up a “lone deaf girl in a hearing world.” That first issue details how she gradually lost her hearing after contracting scarlet fever at age five, and also contains facts about hearing loss and Deaf culture in America. Eight years later, Deafula is likely the longest-running and best-known zine about life as a Deaf person. Her subsequent issues have focused on subjects such as employment, health insurance, and accessibility in zine communities.

In 2010, Radley started Deafula, a perzine about growing up a “lone deaf girl in a hearing world.” That first issue details how she gradually lost her hearing after contracting scarlet fever at age five, and also contains facts about hearing loss and Deaf culture in America. Eight years later, Deafula is likely the longest-running and best-known zine about life as a Deaf person. Her subsequent issues have focused on subjects such as employment, health insurance, and accessibility in zine communities.

As that early quote might signal, Radley’s work explains the difference between deaf and culturally Deaf, and the politics around identifying as one or the other.

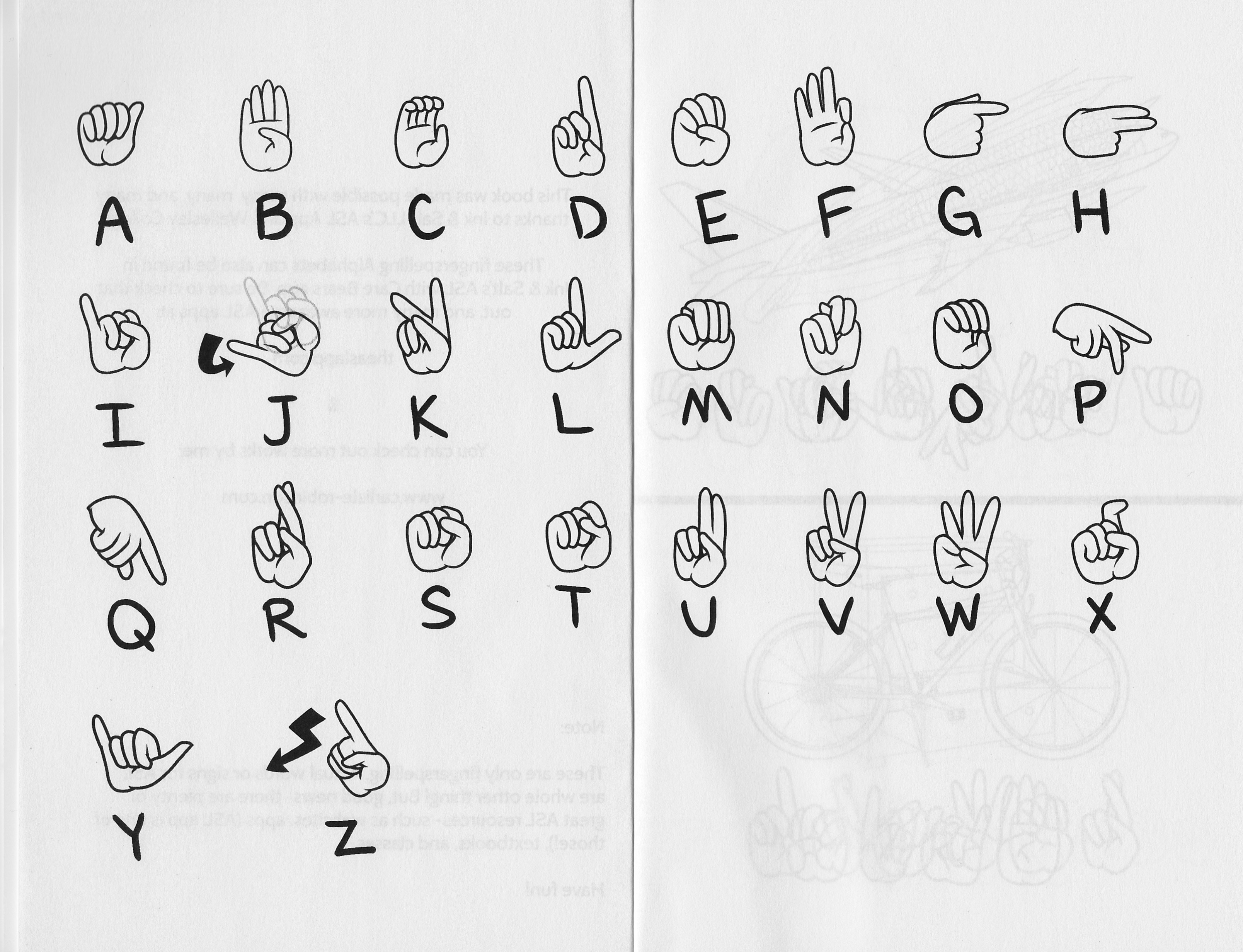

Identifying as culturally Deaf means to “not perceive hearing loss and deafness from a pathological point of view, but rather from a socio-cultural linguistic point of view, indicated by a capital ‘D,’” explains a glossary of terms written by the Canadian Hearing Society. Radley is one of the more prominent Deaf-identifying zine creators, but there is a lively variety of creators and artists coming out of Deaf communities and experience. Like Radley, Toronto-based comic creator and illustrator Carlisle Robinson was born into a hearing family. When it was time for their child to acquire a language, Robinson’s parents got them an American Sign Language (ASL) tutor, started learning ASL themselves, and sent Robinson to a primary school for deaf students.

Robinson acquired Deaf cultural pride through this early submersion in Deaf culture. Having this strong identity helped them later in life when they tried, and later quit, speech therapy.

“I was able to have confidence to tell people and educate them why I don’t talk [or] lipread, and why it is OK that deaf people don’t,” they explained.

Robinson started making comics in high school, but left it behind until they posted a few comics online after graduating from university. The comics got a good response, so they picked it back up. Now, they make comics featuring a variety of disabled characters, including several Deaf protagonists. Robinson hopes their work will reach mainly “disabled people (naturally with a focus on deaf people). But my comics are also geared toward able-bodied people, so they can learn more, and so disability can be normalized.”

Vancouver-based zine maker Jessica Leung began making zines three years ago with  their zines Life Conditions and Deaf POC Poems (which won the Broken Pencil Zine Award for Best Political Zine).

their zines Life Conditions and Deaf POC Poems (which won the Broken Pencil Zine Award for Best Political Zine).

“I thought about how much I really want to share my story and view as a Deaf Asian [Person of Colour]. How I struggle with barriers and notions of communicating as a human being,” explains Leung when asked what inspired them to start making zines. They use zine making to explore the intersections of their identities.

“I am valuing and acknowledging myself as a whole, not [as] separate identities,” said Leung.

The intersecting experiences and barriers encountered by Deaf folks have long played out in zines by Deaf creators. Looking back to the 1990s Riot Grrrl zines, Lynn Y Hou’s zine Cyanide was born from similar desires to deal with varying aspects of identity.

“Part of my need and desire to unleash myself towards the world comes from being someone who has never known what [it] is like to live with natural hearing,” wrote Hou in the first issue of Cyanide in 1998.

But, as Cathlin Goulding explained in her article “The Spaces in Which We Appear to Each Other,” that “unleashing” for Hou meant talking “not only [about] deafness, but also responding to racism and homophobia.

But, as Cathlin Goulding explained in her article “The Spaces in Which We Appear to Each Other,” that “unleashing” for Hou meant talking “not only [about] deafness, but also responding to racism and homophobia.

“The importance of representing a number of experiences and identities is echoed by Sage Willow, one of the creators behind Deaf, What?, a multimedia exhibit representing people who identify within the Deaf spectrum. Exhibiting at Toronto’s Tangled Art Gallery earlier this year, Deaf, What? was conceived by Willow as a way to tackle audism and increase representation of the Deaf community through portraits of community members taken by photographer Alice Lo.

“When you look at the Deaf community, it is mostly represented by white, straight, cisgender individuals,” explains Willow. “There are so many talented Deaf individuals, but they are not being recognized. We need more role models that are Indigenous, Black, people of colour, queer, trans, disabled, and DeafBlind.”

Zines also offer the possibility of a more complex representation. Deaf zinesters are not merely representatives of the Deaf community, but also elaborate their own unique identities.

Robinson’s comic zine What QQ, for instance, contains comics depicting their life as a  Deaf trans masculine genderqueer person. They also create comics such as the webcomic Growing up Trans, which contains elements of how being Deaf factored into their life, but is mainly about the experience of determining their relationship with gender. Likewise, Leung’s Life Conditions features poems about sleep, coming out, and their family, in addition to their relationship to sound as a Deaf person.

Deaf trans masculine genderqueer person. They also create comics such as the webcomic Growing up Trans, which contains elements of how being Deaf factored into their life, but is mainly about the experience of determining their relationship with gender. Likewise, Leung’s Life Conditions features poems about sleep, coming out, and their family, in addition to their relationship to sound as a Deaf person.

Above all, the Deaf artists I interviewed are hoping to raise representation of Deaf folks as a means of reaching other Deaf people and allowing hearing audiences to see what they have to offer.

“I hope that my readers are exposed to new perspectives and are challenged to think about things in new ways,” says Radley.

“Deaf BIPOC aren’t alone with this one,” said Leung, who wants to foster connections and awareness across zine communities, Deaf and otherwise. “You are out there and I know it. [It’s] up to you if you want to reach out and reach me.”