Consider the controversy that follows any attempt to identify the most influential entity in its class. Somewhere, out there, people are locked in arguments about the most important movie, or the most influential album. Hell, even cookware has partisans.

Identifying the most famous fanzine isn’t like this. It’s closer to proclaiming the world’s most famous postcard. There isn’t much in the way of competition. There’s notoriety, Maximum Rocknroll, Sleazoid Express, White Dwarf, but by definition fanzines rarely rise to the level of infamy as what they’re about. Nevertheless, every class of creative expression has its preeminent entry. Its exemplar, or a high score if you will. In the niche of video-game fanzines, there is one that became more famous than any of the software it covered.

In 1983, 17-year-old Satoshi Tajiri created Game Freak, a handmade tips-and-tricks guide for his favourite arcade games. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because Tajiri also happens to be the creator of Pokémon, the highest-grossing media franchise of all time.

“Do you like to collect things?” — Professor Oak

Satoshi Tajiri grew up in Machida, a rural suburb of Tokyo. A budding entomologist — his friends called him Dr. Bug — Tajiri spent the idyllic hours of his childhood catching and contemplating insects. But his favorite pastime was buried, literally, by the pressures of urban development. “Every year they would cut down trees and the population of insects would decrease,” Tajiri told CNN in 1999. “The change was so dramatic.”

In a momentous twist of fate, an arcade center was built atop the pond where Tajiri once caught crawfish. If he resented this change, he didn’t hold it against the structure that dis-placed his former hobby — quite the opposite. Like many boys of his generation, the course of his life was forever altered when, in 1978, he first heard the wub-wub-wub and pew-pew-pew of Space Invaders.

Tajiri was hooked. Overnight, his interest in the natural world was supplanted by a fascination, even obsession, with virtual worlds. “That was the point in my life when my interests instantly turned to video games,” Tajiri told Nintendo Online Magazine in 2000. He began ordering his life around opportunities to abscond to arcades. “I liked video games more than studying, [so] I went to a cram school that was next to the arcade. Whenever I had a 15-minute break at school, I would run to the game center to play Missile Command, then hurry back,” Tajiri said. It was around this time that he acquired a new sobriquet: the earthy Dr. Bug became the giddy ‘Game Freak.’

But in 1979, video gaming was a new hobby with a still-emerging ontology; a new language was being invented to describe it. Even the name of the pastime had yet to be settled. Accordingly, video game report-age — the writing that explained games to the uninitiated, that connected fans to one another, that brought the experience of play out of arcades and into the wider culture — was largely nonexistent. This lack of information was especially acute for cash-strapped players, who could neither play as much as they liked nor indulge their passion vicariously. At 100-yen per session (about .82 US dollars), Japanese arcade games were expensive, more than three times as expensive as games in the United States. If you yourself weren’t playing, you were looking longingly over the shoulder of those whose pockets bulged with coin-age. You certainly weren’t encountering games or their derivations outside of game centers. In circumstances such as these, what was a game freak to do but make his own media?

Special Magazine for Game Life

There’s a funny kind of continuity between Tajiri’s childhood hobbies. He went from playing with insects to playing with bugs — software bugs. Tajiri published the first issue of his fanzine, Game Freak, in March 1983, three years after Space Invaders sieged his every waking hour. It was 14 pages long and sold for 200 yen. A portion of the debut issue is devoted to game bugs and how to trigger them.

He titled it Game Freak after his own nom de high score. “It was handwritten,” Tajiri told TIME. “I stapled the pages together. It had techniques on how to win games, secret tips for games like Donkey Kong.” The issue was credited to “Taji Corp.,” a semi-fictional company, but one that would eventually become the studio Game Freak, the world-famous developer of Pokémon.

This foray into folk media wasn’t entirely unprecedented; Tajiri already had some experience with self-publishing. In elementary school, he made newsletters for his fellow classmates, the expression of a youthful propensity for research and experimentation, and for sharing his innovations with others. In the same TIME interview, Tajiri recalled one such episode from his Dr. Bug days:

“I liked coming up with new ideas, like how to catch beetles. In Japan, a lot of kids like to go out and catch beetles by putting honey on a piece of tree bark. My idea was to put a stone under a tree, because they slept during the day and like sleeping under stones. In the morning I’d go pick up the stone and find them. Tiny discoveries like that made me excited.”

The discoveries that Tajiri published in Game Freak were of a different order than this, but they stemmed from the same intrinsic source of pleasure. With its xeroxed pages and redrawn game screens, Game Freak was obviously handmade: amateurish but hardly naive. In its professional aspirations, Game Freak recalls the early work of Leonard Maltin, the film critic whose fanzine, Film Fan Monthly, rivaled commercial magazines in the scope and seriousness of its coverage.

The discoveries that Tajiri published in Game Freak were of a different order than this, but they stemmed from the same intrinsic source of pleasure. With its xeroxed pages and redrawn game screens, Game Freak was obviously handmade: amateurish but hardly naive. In its professional aspirations, Game Freak recalls the early work of Leonard Maltin, the film critic whose fanzine, Film Fan Monthly, rivaled commercial magazines in the scope and seriousness of its coverage.

A typical Game Freak issue ran to about 28 pages and featured the kind of information that would soon appear in the instruction manuals of retail video games: item compendiums, bestiaries, detailed instructions on how to play and win. Impressively, each issue featured meticulously redrawn game sprites and recreations of game stages. The latter sometimes numbered a hundred or more, a testament to Tajiri’s scrupulousness and his skill as a player. He was also among the first to attempt an historiography of the inchoate medium. In an early issue, Tajiri traces the design influences that culminated in Namco’s Xevious, a blockbuster space shooting game released in 1982.

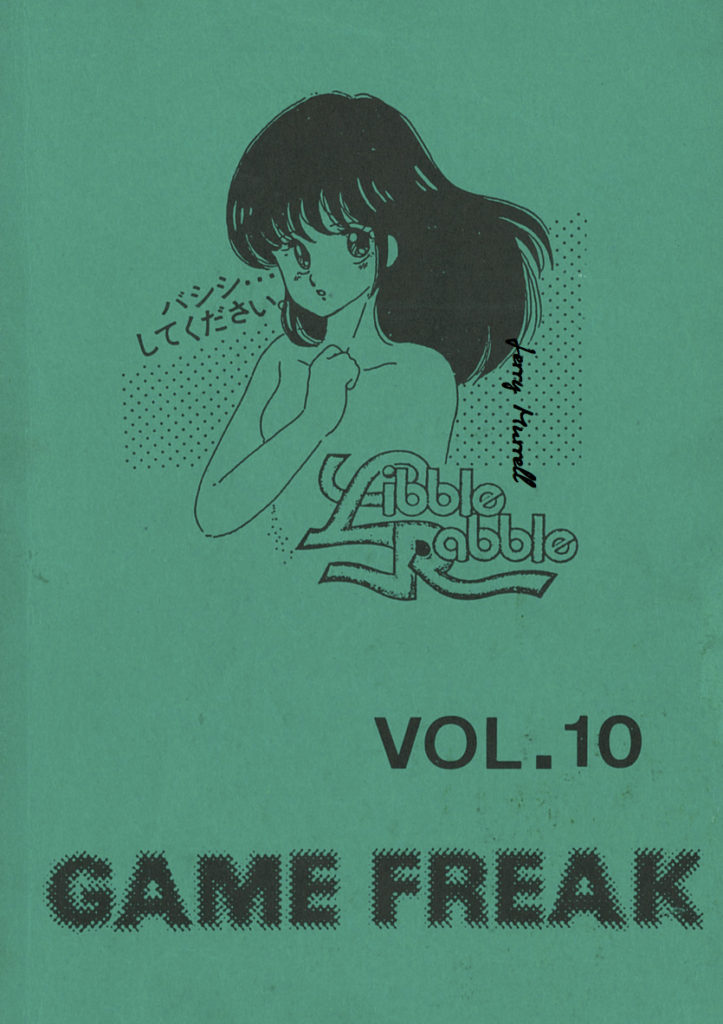

Tajiri had no trouble connecting with readers; after all, they were as starved for information as he was. And as a fan-cum-creator, he was hardly alone. He had the tacit support of the doujinshi community, a loose network of amateur writers and artists who self-publish manga, novels, and art books inspired by (and sometimes wholly derivative of) commercial characters and proper-ties. In fact, Game Freak was sold in doujinshi shops, common in Japan. One of the readers who discovered Tajiri’s fanzine was none other than Ken Sugimori, the artist who designed most of the original 151 Pokémon. Sugimori was so impressed by Game Freak that he wrote to its creator, offering his services from the ninth issue onwards.

Thereafter, Game Freak sported slick illustrations on its covers: manga-style characters in dynamic poses, rendered in crisp lines and shaded with screentone. From the start, Game Freak’s value proposition lay chiefly in the scarcity of the information it contained: “more import-ant than style was selling information,” was how Tajiri put it. With the addition of Sugimori, however, Game Freak’s readers didn’t have to choose between the two.

Game Freak Grows Up

In the beginning, Game Freak’s readership was small enough that Tajiri could manage its production himself using a photocopier and sweat equity. By its 18th issue, he had so many readers that DIY was no longer an option. Game Freak had hundreds of subscribers. A special issue devoted entirely to Xevious sold upward of 10,000 copies. Professional printers were needed.

At the same time that Tajiri was writing about games, he was learning how to make them. In 1984, Nintendo released Family BASIC, an approachable dialect of the already friendly programming language. Tajiri began experimenting with this software, using it to understand “what was actually going on inside the Famicom,” a video-game console released in North America as the Nintendo Entertainment System. Tajiri, ever the autodidact, built a “handmade developing environment” consisting of a circuit board, a battery for storing game information, and the terminals of his deconstructed Famicom. This jerry-rigged system launched Tajiri’s game development career, one that quickly progressed from second-tier puzzle games, such as Yoshi and Mario & Wario, to 1996’s Pokémon, the design and theme of which Tajiri had privately nurtured for years.

Game Freak’s 1987 debut was a tile-swapping game called Mendel Palace. The fanzine that gave the company its name had run its course. Its 26th and final issue appeared that same year. Game development was an all-consuming passion, one that left Tajiri, already prone to working punishing day-long sprints, with little time for hobbies. He set writing aside, but not before leaving his mark on the development of video-game journalism. Making Game Freak had sharpened Tajiri’s insight, his game-making acumen. It helped him forge connections with people, such as Tsunekazu Ishihara, longtime president of the Pokémon Company, who would later prove instrumental to his success. Game Freak transformed him from dilettante to developer. It gave him an audience. In turn, that audience gave Tajiri the confidence to make real his dreams.

All this from a pen nib, paper and some staples.

Michael Hughes is a writer based in Bellingham, Washington. His writing has appeared in: ROMchip: A Journal of Video Game Histories; First Monday; Portal: Libraries and the Academy; the San Antonio Express-News; and VGMO: Video Game Music Online.