When I was a suburban teenager dreaming of downtown, one of my weekly rituals was walking to the grocery store on Thursday and fetching the latest issues of Toronto’s two main alternative weeklies, NOW Magazine and Eye Weekly.

Years before social media became an all-pervading reality, the listings in these tabloid-sized rags were the most complete and reliable sources for all the weird movies and art that felt so far away from central Etobicoke, where haunts like the living room-run Cineforum and thrifty Black Market felt like sea-serpents on ancient maps. For a teenager with a modest income of lawn-mowing money, these free magazines were also cost-efficient sources of entertainment. Killing time with Dan Savage’s sex column or lefty op-eds felt like visiting worlds much different than the dominant media of Toronto’s four daily newspapers.

A lot changed for alt-weeklies in the decades since. The economy cratered and the internet exploded. These two forces combined to dry up ad revenue and erode print media’s cultural centrality. Eye Weekly was gentrified by its corporate owner into a sharply-designed magazine aimed at condo-owners called The Grid. New York’s The Village Voice, the most influential of all alt-weeklies, was bought by a Denver-based conglomerate called Voice Media Group in 2013, which syndicated the same articles across its various papers and chipped away at their local identities. These and most other alt-weeklies across North America have gone under — casualties of their owners’ balance sheets in a tough economy.

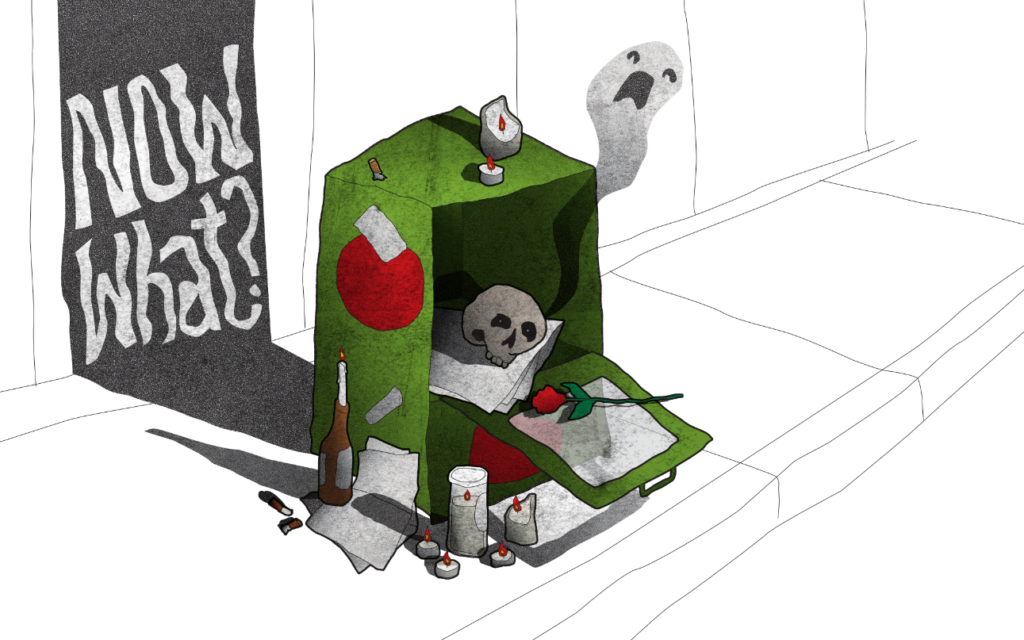

NOW had no corporate owner, and so survived long enough to be sold to one in 2019. After that, it endured a long and very public fizzling-out. Its present incarnation as a cynical content-mill is heartbreaking for anyone familiar with its long history of socially conscious journalism since its founding in 1981. But how many are still around to feel the loss? Over time, many in the demographics that alternative print media has traditionally relied on — young people, racialized people, tenants, progressives — have found Substacks, podcasts, and social media accounts that target their interests with laser-like precision. In this context, are alt-weeklies simply a lost cause? And if so, what has been lost?

At the height of its success, NOW employed over 100 people. “And we didn’t lose anybody,” cofounder Michael Hollett told me. “The dailies couldn’t poach us because we paid just as well.” As the paper grew in the 80s and 90s, it built the financial infrastructure to weather legal threats from ideological opponents and intimidation from advertisers. “We would take huge risks when we had nothing, so the idea of stopping doing that once we had resources didn’t make sense. We always said we didn’t create a newspaper to have a business — we created a business to have a newspaper.”

Hollett left in 2016. In 2019, co-founder Alice Klein sold the business for a modest $2 million to Media Central Corp. Inc., a startup with the ambitious goal of consolidating North America’s remaining alternative newspapers. NOW was the company’s second publication — it previously launched a cannabis-focused website called CannCentral — and the following year it also acquired Vancouver’s Georgia Straight.

“I was the one writing those stupid real estate columns,” remembers Radheyan Simonpillai, a fixture of NOW since 2008. A long-time film critic, Simonpillai became the magazine’s full-time culture and social media editor in 2020. Much of Simonpillai’s time was spent worrying about search engine optimization. In recent years, NOW’s most reliable sources for search-engine traffic were “What to Watch on Netflix” columns and anything to do with local real estate.

Alternative media’s traditional readers (tenants, progressives) would typically be hostile to developers, but numbers are numbers. It isn’t simply a matter of displacing local arts coverage. Pockmarks in legacy institutions leave openings for others to capitalize on.

“Initially when I started doing that real estate thing, it was just me trying to help keep the damn thing afloat,” says Simonpillai. “But that’s when I started understanding more about how the game works.” Reading studies on affordable housing from right-leaning think tanks, then seeing these highly partisan studies reported uncritically elsewhere, Simonpillai saw how a powerful industry can use struggling local media to manipulate narratives. “They’re interested in making people panic about real estate prices to push for more housing and more supply.”

In January 2022, Simonpillai wrote about the provincial government’s Housing Affordability Task Force. He found that most of its members represented interests of the real estate industry and advocated for development at the expense of environmental and social concerns. An article like this runs the risk of alienating the real estate industry, which is full of the kinds of deep-pocketed advertising clients that NOW had been trying to woo.

“Newspapers can be bought by real estate developers,” says Simonpillai. “We questioned the shit we were fed.”

* * *

In September 2022, Media Central Corp’s other main acquisition, Vancouver’s The Georgia Straight, was sold to Overstory Media Group (OMG). A 2021 startup, OMG’s acquisitions include high-profile legacy publications like Halifax’s The Coast and Victoria’s Capital Daily, but its first two years have also been rocky with a wave of layoffs that led OMG editors to unionize in January. Amidst this tumult, The Straight, which was founded as a news and arts weekly in 1967, relaunched last September as a monthly print edition with weekly email newsletters.

“Business is actually not bad,” says Stephen Smysnuik, who took over as publisher with the relaunch. “It is tough being a small media company in 2023 in British Columbia… But The Straight itself is going well. The response is good. We’re six months in and we’re not losing money, let’s put it that way.”

The bulk of The Straight’s revenue comes from print and newsletter ad sales, with website-based advertising a relatively low priority.

Meanwhile in Toronto, a couple of media ventures are aiming to fill NOW’s void. One is The Grind, which launched in late 2022 with a focus on progressive politics and has published a print issue every two months. “NOW had existed as a very political magazine, and had moved away from that in recent years,” says publisher David Gray-Donald. “Toronto doesn’t have an unabashedly progressive publication — especially in print, especially for free.”

A nonprofit, The Grind will rely on donations in addition to ad revenue. “It makes for a more stable publication if, for example, there’s another pandemic or economic downturn when advertising dries up,” says Gray-Donald. Most alt-weeklies have been 100% ad funded, so when that dries up, it’s a real problem.” A successful reader-funded model would also insulate The Grind from the sort of subtle and not-so-subtle pressures that NOW experienced.

With NOW behind him, Hollett has moved on to NEXT, a free glossy magazine available in multiple cities, covering politics and the arts, investing heavily in Gen-Z writers. He hopes to make print media sustainable by discovering young writers like Rayne Fisher-Quann, who joined NEXT’s Vancouver edition as an associate editor at age 19 and now has over 50,000 Substack subscribers. “We didn’t start NEXT just to have me and all of my peers have a new place to go,” says Hollett. “You have to be credible to the younger audience by amplifying young voices. You can’t just be talking at them.”

* * *

To what extent publications in the tradition of alt-weeklies can survive — whether weekly or monthly, corporate-owned or independent — is an open question. What is clearer is what we lose when they go and the corporate narratives that take their place.

One of Simonpillai’s proudest moments at NOW occurred in November 2020 when he broke a story about Telefilm Canada’s Fast Track funding program. The program, which automatically allotted around 30% of Telefilm’s annual budget into projects by Canada’s most financially successful producers, was suspended during COVID (during which there was little box office success to measure).

“Think about it: a two-week commitment from a salaried employee to write a story that specifically speaks to the tiny-ass Canadian film industry. You’re not getting a lot of eyeballs for that investment,” says Simonpillai. “But [my editor] says, ‘If you’re passionate about it, you believe in it — go for it.’ I dedicated two weeks of my job, plus the resources from the news department to lawyer it, to break that story. I can’t imagine anywhere else where I would have written that.”