Kari walked north from Julie’s apartment into crowded Mongkok, a working-class neighbourhood north of Tsimshatsui. It was a warm mild Tuesday afternoon. Kari turned onto Shanghai Road, a street lined with discount electronics stores, then an alley full of clothing stalls, before she reached her favourite open-air food stand. The daipaidong was run by a sixtyish bear of a fellow. Leung Sook, Uncle Leung, as all the regulars called him, dished up bowls of steaming wontons in a rich fishy broth. He wore his usual outfit, a pristine wife beater, khaki shorts, rubber sandals and a pale doughnut-shaped jade pendant on a silver chain from his neck.

Uncle Leung flashed the thumbs-up sign at her. “Good, hah?”

Kari ordered a side dish of vegetables, and today, it meant iceberg lettuce, lightly braised and served with oyster sauce. Other customers came and ordered and he collected bills and coins from them before they sat at the folding tables. Kari plucked a pair of plastic chopsticks from a green plastic container, and he poured her some watery tea as wafting sounds of Cantonese opera came from his boombox.

“You Chinese?” He jabbed his ladle at Kari. “Daddy Chinese?”

“No, my mother.”

Kari never thought much about being of mixed race in the States, especially in San Francisco. She looked more Asian than white; her nose was slightly bigger and people always said her eyes were “exotic,” which she considered a somewhat silly remark. Several of her friends were mixed, Terry Thomas was Black and Vietnamese, the Johnson twins were Japanese Italians, but here, it seemed necessary that everyone classify her, to identify who she was and determine where she was from, from Uncle Leung to the girls at Mercedes to Eva’s parents.

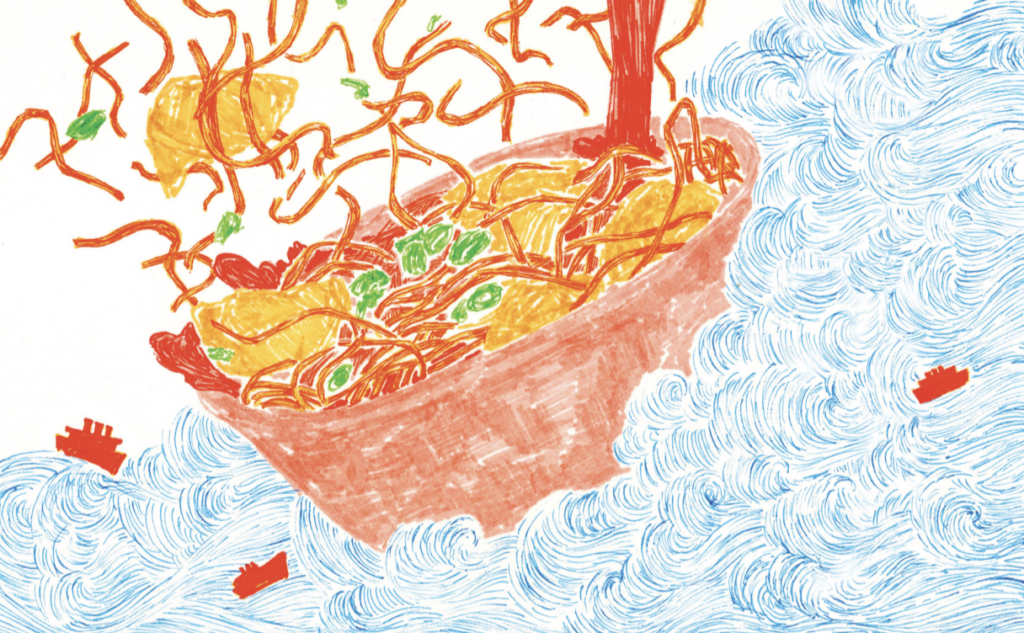

Uncle Leung’s food was hearty, the egg noodles al dente, served with a pinch of green onions in a broth so hot Kari felt the steam in her nostrils. Home-cooked food made by Uncle Leung with much pride, as he brought out each bowl and firmly placed it on the table, along with the whole notion of being comforted and cared for, came as a revelation to Kari. She missed that growing up.

Her own mother had bragged about how she never cooked. Their primary diet consisted of Mexican or Vietnamese takeout and leftovers from expensive French and Italian restaurants her mother had brought home from her dates. Being in Hong Kong made Kari think more of family than she ever did in the States.

On the street where she sat slurping her noodles, Kari watched a group of uniformed children skip down the stairs of their school a few doors down, with their satchels and backpacks, and rush to their dai pai dong, adjacent to Uncle Leung’s. Girls wore plaid dresses with Maryknoll Convent school appliques, while boys had pristine white shirts and grey ties. The girls giggled, mixed with delighted squeals, as the boys teased each other throwing playful punches that often connected. They spent their allowances on fried tofu, chicken wings, squid, tripe, and fish balls, skewered onto wooden sticks, which they ate rapidly in order to catch every last drop of sauce.

“Mmmgoy!” Uncle Leung half-shouted at Kari. “Excusah me!”

Kari chuckled. He taught her a few words of Cantonese every time she came to his dai pai dong. “Mmmgoy,” she repeated.

“Daw jie!” he said. “Thank you!”

“Daw jie,” said Kari.

“Goodt!” Uncle Leung opened a bottle of Coke and gave it to Kari for passing the lesson.

In the morning, the monks chanted, as they paraded through the streets, tapping cymbals as people set out small homemade altars with fruit, incense — all offerings to the dead. Further down Lascar Street, off Cat Street, a man with slicked-back hair, a pressed short-sleeved blue shirt and polished loafers laid out a blue paper Mercedes, a stack of US 100 dollar bills, a paper Rolex, several paper diamond necklaces, and a replica mansion, preparing to send them to people in the afterlife. He struck a match. The paper lit quickly; its flames, vermillion and orange, singed the paper and rapidly turned it all into ash that began slowly floating skyward.

Kari looked out the window from Ryo’s apartment. Ryo, who left early for an appointment, had given Kari a spare key. This gesture represented another level of intimacy that she hadn’t had with any other man. She went to the refrigerator, where she knew he always kept pink grapefruit juice. Drinking juice out of a goblet, Kari watched the procession and all the small fires lighting up the neighbourhood.

Kari liked fire. God, she had set enough of them growing up. And when she wasn’t setting them, she had candles lit as often as possible.

Offerings to the dead, what would she send up?

To Bonnie, the high school girl who hung herself after no one listened. She kept that a secret to the end, she left no note. It was senior year. Was it failure to get into the holy trinity of future success, Harvard/Yale/Stanford, or was it her boyfriend, whom her parents hated because Jorge wasn’t Chinese, or was it that he was two-timing her?

She was that close from leaving the city, forever if she wanted. Instead, the senior class dedicated a yearbook page to her and the graduation became a sombre tribute. In death, she finally got the attention she had craved.

To Melissa, who slit her wrists in repeated attempts, either in the wrong direction or never deep enough. Finally she succeeded when she ceased the cutting and made the most extravagant attempt by throwing herself off the top of Campanile. A horrid, bloody, messy end. Every detail was devoured by every news outlet from the university paper to the local stations. The story of the Cali Golden Girl was harder to decipher.

Kari decided that if she could have them in miniaturized paper form, she would collect and send Bonnie a round-the-world plane ticket, a copy of Duras’ The Lover and a box of See’s chocolates.

The typhoons came at the end of May. From their names — Marakot, Nuri, Banyan — which intrigued her as to their origins, to being safely indoors watching and listening to the rains and wind lashing the windows, slapping the buildings, Kari had learned to love typhoons.

The city would shut down, as if getting ready for a deep sleep, when the announcements came blaring through loudspeakers in Cantonese and English.

Ferries stopped, as shopkeepers began shutting down, taking in electronics, fruit, clothes from the street, pulling down metal screens or boarding up windows. Awnings came down; shoppers exited from multi-storied edifices with armfuls of designer bags, or from spartan stands with thin plastic ones, beginning their escapes to buses, taxis, the last MTR.

The bolder establishments jeered at the typhoons and offered storm sales, drink and snack specials, daring those to stay out, to defy nature, to come in and consume a bit longer.

Typhoons made Kari feel human, small and mortal.

Susanne Lee’s writing on Tiananmen dissident Ding Ziling, Spanish surrealism and sausage, menhdi in Delhi, and the Vietnamese Reunification Express has appeared in the Village Voice, The Nation, Konch, Giant Robot and SLAM. Among her short stories, “Vol de Nuit” appears in PowWow: Short Fiction from Then to Now (DaCapo), and “Chungking Masala” was a runner-up in the Guardian Openings Contest. After attending Harvard, she fled life as a businessgirl at the World Trade Center to write.