By Joey Comeau

George woke up and remembered that he remembered giraffes existed.

It had come to him the night before, at the office Christmas party, an image of faded orange and white on his sixth drink. He spent the rest of the party interrupting conversations to tell his co-workers “I can’t believe I forgot about them. The necks and the spots and everything. The little tails.”

He moved from circle to circle, not hearing their snickers behind him, his mind flooded with the grainy video of those public television programmes he’d seen as a child, long faces with nubby protrusions on top. Long tongues snaking out for leaves. How could he have forgotten such long tongues?

Having forgotten giraffes for so long was an embarrassment of the type you had to purge by telling as many people as possible, the type you had to reduce to a joke as quickly as you could. He made his way to where his friend Matt was chatting up a girl. The girl watched him approach. She was swaying a bit, drunk, though her drink was perfectly steady.

Matt looked up and smiled when he saw George. They’d shared an office for six months, something like three years ago. The younger man kept a map of the solar system above his desk, detailed and covered with distances, temperatures, masses. Numbers and charts filled the void between planets. The temperature of Venus was circled with a red marker. George tried to imagine Matt ever forgetting something as important as giraffes.

“You came!” Matt said. “I knew you would.” He turned to the girl. “This is George,” he said.

George smiled and put his hand out. She probably remembered giraffes too, he thought. She couldn’t be more than 20. She probably still lived at home with her parents, maybe lined her room with zoo wallpaper, giraffes and lions. Her shelves would hold teddy bears. They would be soft like the skin just down from her shoulder, where her breast met her body. That spot was hidden now, under her shirt, but George knew it was there. Soft. He realized he’d had too much to drink and he was staring.

She shook the hand politely, looking past him at the crowd, bored.

“Listen,” Matt said, leaning closer to George. “There’s a promotion coming up, and I’m going to drop your name. You’re overdue.” As he said it, George felt the faint stirrings of anger. He’d been passed over twice now, in favour of Matt. The only reason Matt was in a position to ‘drop his name’ was because he’d taken promotions that should have gone to George. Still, the feeling passed quickly, and he pulled Matt close. He raised his voice above some braying woman across the room, and he said “Do you remember giraffes?” Matt shook his head.

“What?” he said, like George was joking.

“Giraffes!” George said, louder. “With the long necks and the awkward knees? Do you remember them?” Matt laughed again, and nodded.

“Giraffes!” he said. “Of course. Mary in human resources is obsessed with them. Her office is full of books and those cheesy inspirational posters. ‘Reach for the sky!'” George tried to think of where Mary’s office was. He was sure he’d been there. Up on the 19th floor, probably, with the other executives. Someone had abandoned their drink on the table between Matt and the girl, and George picked it up. Coconut.

“Can you show me her office?” he said, and Matt looked back at the girl. He grinned.

“Sure,” he said to George. To the girl he said something that George couldn’t hear, then kissed her on the neck. George started for the elevators, not looking back to make sure they were following.

Lying in bed the next morning, George tried to piece together the rest of the night. He rolled over and he shook his wife’s shoulder. She said something into the pillow.

“What time did I get in?” he said. “From the party last night?” She pulled the blanket up and turned deeper into the pillow. He remembered standing in Mary’s office, the light coming from a little table lamp, giving the room a warm feel. Where had Matt and the girl been?

He remembered the elevator ride up. He stood to one side, pressed as far against the wall as he could while Matt and the girl went at it, pulling at each other’s clothes, their kisses mashing their faces together. He looked at his feet, and he ran his hands along the seams of his pockets.

When the elevator opened on the 19th floor, George stepped out and held the door. Matt pointed up the hall.

“At the end, there,’ he said, and he took the girl’s hand, led her the opposite way, fumbled keys from his pocket. George watched them go. The girl pulled her shirt up as they reached Matt’s office. Matt fought with the lock, and in the split second before they went inside George could see her naked back, spotted and dark in the hallway. Then the door was closed, and the frosted glass was yellow with the light beyond.

George found his way to Mary’s office, the hallway only half familiar in the darkness. Her door was locked, and George pressed his face against the cold glass, trying to make out the office inside. He hadn’t been in Mary’s inner office during the interview. He had never even met Mary. The secretary had interviewed him at the desk in the outer office. There hadn’t been any giraffe posters there. He would have seen them. They would have reminded him earlier that giraffes existed.

He tried the door again and it was still locked. There was a big brown smudge in the office behind the frosted glass, the secretary’s desk. George turned and made his way back down the hallway to where Matt and the girl were. As he came around the corner, he could see that the light was still on. George steadied himself against the wall. Matt would have something to drink in his office, he thought.

But there were sounds coming from the room, and shapes just beyond the glass. There was music playing, and the girl was saying “yes,” over and over. George stopped with his hand on the doorknob, and thought about knocking. He could just turn around and get back on the elevator. There were drinks at the party downstairs, and they were free, but he didn’t feel like seeing those people now. He was tired.

If he knocked, Matt and the girl might hurry into their clothes. They might give him a drink if there was anything in the office. But more likely they would just tell him to get lost. He’d end up standing in the hallway just like this, ashamed. He began to turn the knob anyway. Who cared what they thought. He needed a drink.

But the shapes moved closer, and then the girl was up against the frosted glass, mashed into focus against the white, her breasts outlined perfectly, flat and out of shape. The two figures were moving rhythmically against the door. He could see her mouth move with every “yes” and he could see Matt behind her, a dark pink shadow. If someone came along now, someone else from the party, they would think George was a pervert standing in the hall like this. And if he could see her, couldn’t she see him? George stepped back. He should just turn around and get on the elevator.

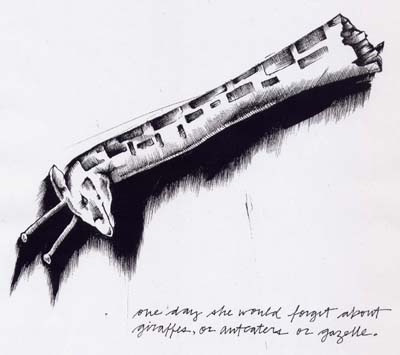

Instead he reached out and put his hand against the glass where her breast was. He imagined he could feel the warmth. One day she would forget about giraffes, or anteaters or gazelle. He let his fingers linger against the door, and then turned around and walked to the human resource office.

He kicked the frosted glass of Mary’s door and it fell around his leg. The sound was a quiet crack. He pulled the big chunks of glass free, and reached through to unlock the knob. The outer office was just as he remembered it, plain and beige. It was a bit more sinister in the darkness. The walls of her inner office were decorated with pictures of giraffes, like Matt had said, giraffes pulling leaves from trees, giraffes with their tongues reaching out, twisting. There were some tribal looking giraffe statues in the corners, and the shelves were lined with little giraffe knick knacks and books.

This was someone who thought about giraffes every day, who took pride in her love for the slender animal. When she got presents from coworkers, they knew to get her giraffe-themed gifts. George wondered how many of the knick knacks were gifts from his own coworkers. He wondered if Mary from human resources kept something to drink in her desk. He looked. There was a bottle of gin in the bottom right drawer.

While he drank he rifled through her things. None of the papers on the desk were interesting. It was only personnel reports and job applications. He turned on her computer, hoping to find his own personnel report, but it asked him for a password. He tried “giraffe”, and was denied. He knew what the report would say, anyway. He was useful in his current position, and that position alone. He’d reached the top of his personal corporate ladder. There wasn’t anything interesting on the computer.

George stood, and looked around the room for something to pick up.

The wooden giraffe sculpture was heavy in his hand, like a club. He swung it a couple of times in the air, getting the feel of the weight, and he looked around at the dark office for something to break. Mary from human resources didn’t forget things like giraffes. She surrounded herself with them.

George tried to put the statue through the computer monitor, but it was one of those new flat screen things, and the picture just cracked and bent in on itself. There was no tube to explode and it was unsatisfying. It just made him angry. He pounded on the monitor with the heavy wooden giraffe, little shards of the screen falling across the table and to the carpet. He pulled the computer itself out from under her desk and started hammering the side of it, trying to break through the metal casing with the idiotic long-necked conversation piece. He dented the machine quite badly, and pulled all the cords out of the back.

He busted every light and pulled down the giraffe posters, hoping to tear them up, but they were mounted against some sort of wood. He managed to break one of them in two, propping it against the wall and stomping on it. He swung the giraffe in wide arcs, sweeping knick knacks to the floor and breaking as many as he could. It wasn’t until he began pounding the giraffe on the big plate window that he realized the girl was standing in the doorway, smiling at him.

“Do you need any help?” she said, crossing to pick up another of the heavy giraffes from the corner. She joined him at the window, took a step forward, brought the giraffe down over her head and put a good crack into the reinforced glass. “My name’s Julia,” she said, lifting the giraffe above her head again. “Matt passed out on his desk,”

George nodded and pointed at the bottle of gin. He took a bit of satisfaction in Matt’s failure, but he couldn’t let it distract him. He didn’t want to lose his momentum. He wanted to break through the glass, to let the cold air into the office. He wanted to throw these knick knacks and expensive statues down into the courtyard below.

“There’s gin there,” he said. “Help yourself. It’s not mine.” And he hit the window again, as hard as he could. Julia set the giraffe down again and took a drink. After a couple swings, he needed to rest. “Do you work in the building?” he said. “Or are you a friend of Matt’s from somewhere else?”

“I’m an accountant,” she said, and she leaned closer to George. “But really I’m just biding my time.” She winked, and George smiled. “I just met Matt at the party.” She lifted the giraffe again. “He seems sort of boring.” Her giraffe punched a hole right through the glass, and fresh air suddenly swept into the room. She stepped forward so that her face was near the hole. George did, too.

“He is,” George said, taking a deep breath, letting the cold air fill his lungs. The wind was sweet against his face, and she slid her hand into his. They looked out at the offices in the next building.

She let go of his hand and went to the desk for another drink. George stayed at the window, looking out at all the other offices. How many of them had animal posters on their walls, giraffes or ducks, or baboons? George wondered if there were any other animals he’d forgotten.

Julia took his hand again from behind.

“This,” she gestured around at the damage. She kicked the giraffe at her feet. “This was nice,” she said.

“Help me with this stuff,” George replied, indicating the scattered curios and figurines all over the floor. He scooped up a group of little stone giraffe carvings, and carried them to the window. They fell away into the darkness.

The two worked quickly, stopping only to bash the hole a little wider, so they could throw the posters out as well. The last to go were the giraffe sculptures, and they let them fall headfirst, spinning slowly. Watching them fall was like watching the ball drop at Times Square, New Year’s Eve. It was like watching a penny fall into a well. He wanted to close his eyes and make a wish.

Joey Comeau lives in Halifax, where he studies linguistics. He writes the weekly comic A Softer World (www.asofterworld.com). He likes you?