The sharp blade makes an effortless cut, and the first thing I think is “like plastic,” a stupid, stupid thought, but then I wonder why my mind would drift at all given how the knife is now stuck in the bone that’s inside of my husband’s neck. Here I went and hesitated, and him always going on about being deliberate and committing, and I saw what I did wrong right as I was doing it, a stupid novice who would know better next time. If only I had been a bit more deliberate, his knife would have lopped his head clean-off so that the jagged, fleshy bits that kept his blood from evenly seeping out would have instead been smooth and sweet, at least to the naked eye.

Still, the blood creeps over my hands and down his front as his head lolls, his heart nearly defeated, but still swinging in final, jabbing spurts that are thicker and more viscous than anything else it threw out during its entire final fight, and I let the knife go so that he drops to his knees and pitches forward so fast and hard that his mouth twists into an odd expression, a misshapen, stupid hole that can no longer speak about needing to leave his woman in the desert with nothing but spoiling blood, nothing for miles and it is so hot that all she can do is sleep through the days to forget about the empty freezer, nothing to drink but the gallon jugs of blood that had spoiled before the end of the week, the only company out here being stars and endless sand, and never any rain.

His fault for showing me how to use the knife after he couldn’t get away from the shop one night. “A butcher’s wife should know how to kill and carve her own meat,” but I knew nothing about hunting and couldn’t learn since all but the smallest animals were extinct.

When he had come home today acting like nothing happened, I dumped the jugs of bad blood on his hood and threw the empties at him, screaming, “I could have died!”

“Shut up,” he had said. “I said I’d be back, and I have fresh blood and some fruit, too, except now I’m feeling less than giving.”

“What kind?”

“Thought so.” He pushed me aside and went into the house. “Bring the bag in with the cooler.”

He worked in town at the butchery where those of us who wanted to cash in could be “let” by an expert, your blood drained out after being strapped upside down so that men like my husband could more easily remove your head. Advanced filtration removed most of the impurities until the blood became safe enough to drink, and the dehydration chiefs took care to press the moisture out from the meat, which left us with something like a kind of water and a kind of jerky. The water trucks that passed through the wild, out where we were, were guarded with guns, and besides, we were all dying. We had downpours three, maybe four times a summer, and the pollution and the synthetic food gave people every kind of ailment. Eat enough of what the plastic packages called nutrients and you’d live a year at most.

“You hear about the comet?”

I tore off a hunk of meat and savored it even if the first thing that came to mind was whether it had also been a woman. “Yeah, but still a year off.”

“Doesn’t matter. You should see what’s frozen. Feed the whole city for at least three years.” He poked his straw, a rigid piece of plastic, its end encased in metal, into one of the bags and began drinking the pinkish liquid. “Nice to think I could stop this shit. And you could stop eating Eve. Or was that Juan? I forgot.” He jumped back when I grabbed the knife, but I was too quick to think through what killing him meant I would have to do.

“Protection and money,” my mother would say. “In the end, that’s all they’re good for.” My husband had felt sorry for me until his disgust won out sometime during our sixth or seventh year and he put me up out here and lived his real life in town with the other butchers who did what they pleased throughout the week.

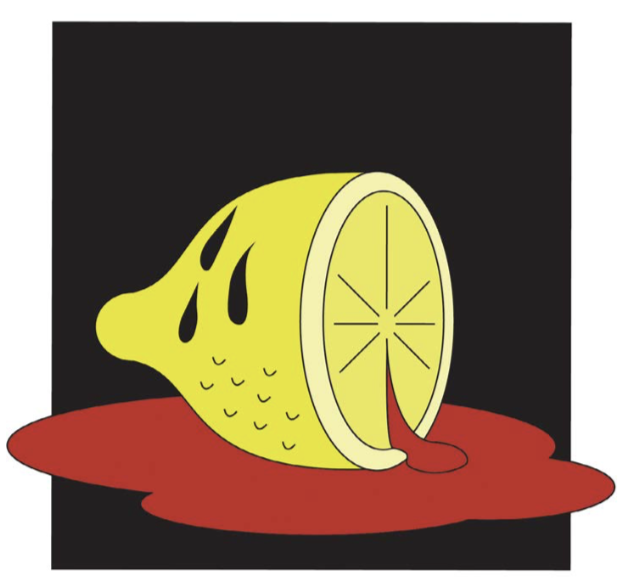

The fruit he mentioned is an overripe lemon wrapped in opaque plastic at the bottom of the cooler beneath the bags of blood. Once you get past the skin, the insides taste just like how I imagine the beach regions feel, the water in the air, the sunshine more kind. One time, a beach region outcast changed his mind about being let at the last moment, and my husband uncharacteristically listened to his plea to be saved in exchange for an orange. My husband still strapped him in and slit his throat though. “Can’t beat free.”

Two hours later I’m almost in the next zone but my fuel’s low, so I stop and flash his chip under a scanner and notice others eying my car’s waxy black sheen and its streaks of dried, pink blood. For all I know my face and hair are also spattered, and when the chip doesn’t read and the attendant looks up, my hand is shaking and I think I’ll just drive away until a man at another pump speaks up.

“Do it faster.”

I try and the reader beeps, so I smile, but he’s noticed the car. “My husband’s a butcher,” I say as if this will explain such flagrant waste, and the man nods without asking the obvious question about why I’m out here alone, a woman out-of-doors in summer.

“Be safe now.”

I fumble with the gas hose and spill a drop that burns its impression into my skin it is so cold, and I can almost hear my husband blurting out how we found enough energy in time to run out of water, one of the many phrases he restated like the slogans from the old ads he had amassed—“From cars to freezers, we found enough energy to get you to the next oasis,” which would be true if you could choose where you were born and didn’t have to navigate past an army at every border who would only let you pass with the right papers.

My car rockets down the road with a full tank that will last through Flagstaff where some lucky fuck will trade me for my mostly new car and the small fortune in its trunk, and when the streetlights end and I turn on my highbeams the darkness covers them like a skin.

Every summer the stations play the sound of water at least a few times an hour, a metal squeak followed by flowing H2O, the rush of gushing, dripping liquid bringing to mind an actual wet bath and not the dry sanitizer we always used at home, and by now I’m tired, it’s halfway through the night, and I turn into a dusty motel parking lot that’s empty excepting one other car. I swipe my chip under the scanner to receive a plastic key, but when I step into the room, something immediately feels wrong. I can’t quite see him, but a shadow in the corner speaks.

“Get on your knees,” it says, and I do, and it turns on a light and he stands there, huge. The walls in the back of the room have been knocked out to make a crazy, makeshift floorplan that he must have designed with what looks like a giant hammer now resting by the bed. When he moves, his heavy steel-beam legs extend the structure of his body, his head nearly brushing the ceiling. “What did you bring me? Do you have blood?”

I want to say five quarts, a bad joke and probably the wrong approach, but instead I say nothing and he kneels down to see my face.

“Well?”

But something in my expression changes his demeanor and then he’s turning me over and I’m kicking and clawing until he pins me.

“Struggle and I’ll knock you out,” he says, and I must have moved because I come-to and my brain’s throbbing and the giant is driving and it’s almost night. I’m roped up in the backseat and he’s hunched forward in order to see, and there’s a stinging between my legs that I refuse to believe.

“You wouldn’t stop wriggling.”

“Where are you taking me?” There were several quiet seconds. “This car’s a nice fit.”

He laughs, which is the best start I can hope for.

“When I first saw you, I thought that you must go through a lot of blood. So you have to be resourceful,” I say. “And smart.”

“No, just observant. You ever see a spider?”

“When I was a kid.”

“I’ve watched and I’ve learned. I only take what works.” Big swirls of dirt blow over the road, and we drive right through them, nothing but dust for a half-minute and the giant spider keeping up speed, and when it clears, the desert looks different, the hills striped in bands of red, brown, and pale green. “They call this the painted desert.”

“How long was I out?”

He laughs. “I gave you something to make you sleep.”

I have a dim memory of waking and him pulling over, but it didn’t feel quite real. “Can we have some music?” I ask but it’s nothing but ads, so he changes the station and as the sound of the running water plays we become exactly the same, if only for a moment, and he squeezes what’s left of one of my packets, draining it through his straw.

He tosses it back and it hits my head. “There’s still a little left.”

I manage to twist my shoulder and tilt the few inches it takes to get to the straw, and as the blood coats my throat I immediately want more. “You know they play those to make us thirsty?”

“I know.”

Before my husband there was Mike, the Southwestern Regional Media man who left as soon as he made enough to buy a visa to the Pacific. He promised we would leave together after his next promotion, but when it finally came he left in the night without waking me. It was SWRM that first hawked blood to solve our problems with water, and the butcheries came soon after that first summer.

They scaled up their ads in the summer, water audible almost everywhere within city limits, footage of gentle streams and soft rain on every device with a screen. You could stop watching about as easily as you could keep your mouth from watering at the smell of roasted meat, and the tagline, “The source of all good things,” was redundant when faced with the spectacle of real, flowing water. No one in the desert had ever seen a mountain stream or a river bursting with meltwater, but being transported to one, even for a moment, answered the prayers we all asked on those days of driest heat.

At summer’s peak, you couldn’t buy water, and the price of blood went up. People stayed inside and only went out at night when the billboards weren’t as visible and the sounds played less often. The number of people willing to be let escalated.

“You know that years ago we had huge underground lakes? If you dug deep enough, water would bubble up.”

The giant turns off the radio and listens.

“My mother’s grandfather dug wells when he was a kid, back when there were states, and he’d go out on their ranch, out past the pens, and wander around with the same stick his grandfather gave him. He was so gifted that was how he made his living.”

“Lie.”

“It’s true.” The car hums, cutting through the desert, and I’ve been flexing my wrists against the bite of the ropes. “Back when he dowsed, people sprayed water on their dry fields to grow crops. Big, thirsty animals like cows drank up more water than an entire family and they thought nothing of it.”

“Which ruined us. No one cares about the future.”

“Just the same, I’d like to go back. I wish I could see one of those underground lakes. I would take off all my clothes and jump right in. I wonder how it would feel, wet everywhere, the smell of it, water all over your skin. I would get all the way under and just drink. I would let it wash over my body and my hair. I would live down there.”

“You’d drown. Unless you can swim?”

I look at the back of his head, the dense brown tangle of hair, his neck thicker than the headrest. “I like to dream about it. I want my naked body to be covered in water, waves of it.”

“Stop talking.”

Through the windshield a new moon appears on the horizon. The stars are coming out. “You ever been with a woman?”

“What’d I say?” He accelerates, and the engine whines, but he can’t help himself. “More than one.”

“I figured. But you never know. Some worry about the exertion.”

“No, it’s the best use of fluids.”

“You ever hear of induced lactation?” When he doesn’t answer, I keep on. “It’s a treatment to get for your breasts to produce milk. When you’re with a woman who’s induced, you can suck her dry. My husband loves it.”

He turns around to see if I’m serious, and I smile.

“After the first time, he wouldn’t fuck me otherwise.” This time, I think he forgets to breathe and the car fills with tension.

“When were you last treated?”

“Last month.” I wait. “Keep me hydrated and you can drink until you’re full.”

The car slows, and the giant pulls off the road and kills the engine as I shift my head and lift the straw with my mouth and fling it behind my back, close to my bound hands, and I try gripping the slippery thing between my fingers, but then the door opens.

The giant tugs on my legs, and I hit the ground, hard. He’s got a knife, and he turns me over and cuts the rope around my feet, and I stay utterly still as he cuts the ropes from my hands and takes off my pants.

“I tried before but you were dry as a bone.”

“Please,” I say when he pins my arms back. “Please, I want to touch you.”

He grunts and lets go and slips the knife into a sheath, and he flips me onto my back one-handed, breathing hard as he straddles me and rips my shirt open. He squeezes my breasts with his massive hands, and when he buries his head in my chest, I run my fingers through his hair, tugging it and then bringing my hand to his cheek, his neck. He moans, and with my other hand I find his ear and tease it with the finger I don’t have wrapped around the straw, which I pull back, measuring its angle just before plunging it straight into his skull, and he howls until I bang it in further, and he rises, scream- ing, blocking out the sky—and then it’s over. Whatever’s inside of him leaves, the light in his eyes, and he topples to one side.

I wriggle and push him the rest of the way off me before I can stand up, and his body lies in the sand, blood dribbling down from his mouth, and I reach into his pockets for the keys.

In the trunk, the cooler is wedged between his things—a black bag, the sledgehammer and a box of tools. I’ll take stock later, but I need a drink, so I take out a cold bag of blood and swallow every drop, thirsty for more but knowing I should hold out even as I linger over the open cooler. In a few hours, dawn will come and I’ll make my way through another hot day. I reach to shut the lid, and I see it—my little bag. The giant threw it in there, and I’m grateful because I’ll change into the fresh clothes, and at the bottom I’ll find something else, the cold lemon.

Back on the road, I’ll bite through the rind into the cool fruit, its juice bright, and I’ll drive.

Sean Wheaton is a buttoned-up college writing instructor whose heart beats with punk fury. He lives in Portland, Oregon.