Leaping from advertising producer to comic publisher in a single bound, Annie Koyama has achieved the unthinkable with Koyama Press

by Natalie Zina Walschots

Not many publishers can boast a superhero-like origin story; but Annie Koyama, founder and owner of Koyama Press, has a tale that rivals the beginnings of many a powerful do-gooder.

Koyama began her professional life as a producer and an assistant director for Canada’s National Film Board. She eventually moved her focus from feature films and documentaries to the commercial world where she established a successful career in advertising. After a full 10 years on the job, Koyama decided to take a leave and spend some time travelling.

However, instead of heading out on a year of exploration and adventure, Koyama became ill and was eventually diagnosed with cerebral aneurysms.

Here is where her story becomes extraordinary: while her original prognosis was terminal, in late 2005 Koyama opted for risky surgery to correct the weak and bulging veins deep in her brain. The procedure was a complete success but required a lengthy period of convalescence. As if her story wasn’t remarkable enough already, Koyama played the stock market while she healed and built up a comfortable nest egg for herself. Then, instead of returning to work, she decided to do something crazier: invest her money in comic artists.

While the decision seems like a dramatic departure from her path, Koyama has a life-long love affair with the format. “For me, there are the nostalgic memories of growing up with certain comics. Anyone fortunate to have a parent patient enough to read to you as a child can’t help but naturally carry forward that interest,” she says. “Good artwork is good artwork whether it appears in comics or fine art, I think.”

In the wake of her illness and recovery she decided to focus on projects that she cared for deeply, and the love that defined her childhood would eventually become her second career.

Koyama describes her decision to establish a press and support comic artists with no formal experience with what it turns out is her trademark talent for understatement and humility: “Perhaps, I have a pretty good tolerance for risk-taking and honestly, I hadn’t planned to start a publishing company when I approached the first artists,” she says. “To start a business in which you have absolutely no experience nor knowledge seems pretty foolish but I like a good challenge and am a pretty quick learner.”

In other words, there are probably Navy SEALs with less risk tolerance than Annie Koyama. Fiona Smyth, creator of

the zine The Wilding, has “had a peek into the herculean tasks [Koyama] has performed as a one- woman-army publisher.” She says that in addition to superhuman strength, “Annie’s taught me about tenacity, sticking to your guns in the face of adversity and following your goals in a very grounded, kind way.”

Koyama has attained superhero comparisons not only for her extraordinary backstory, but also for her unorthodox business model: Koyama Press, at its core, is founded on altruism. When she started helping comic artists in 2007, Koyama didn’t set out to found a press, but instead sought to help comic artists she liked, funding their projects and giving them the proceeds from the sales. It wasn’t until later that year — with the release of the book Trio Magnus: Equally Superior by Aaron Leighton, Clayton Hanmer and Steve Wilson — that Koyama finally founded Koyama Press and laid out her mandate to promote emerging and established artists whose work she admired.

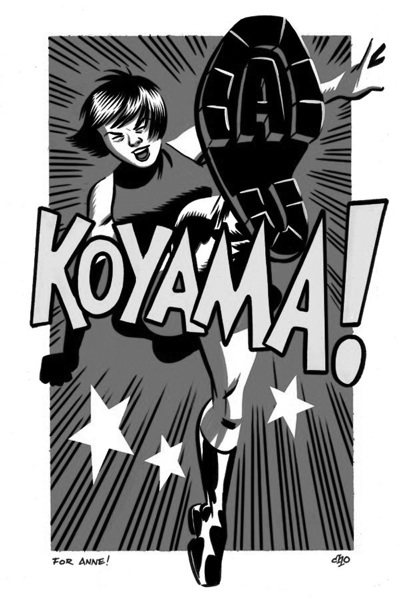

Kickass Annie by Aaaron Costain

Kickass Annie by Aaaron Costain

Aaron Leighton, who has now been published twice by Koyama Press, feels that the level of support Koyama gives to the artists she works with is unique. “She is one of those rare birds who is a great businessperson and also extremely generous, and she truly cares about her artists and their work. Also, many of her artists had never been published before until she gave them their first break.”

The premise of Koyama Press’ work would be remarkable enough if it were merely generous, but what makes it even more amazing is that this comic press with a goal to fund projects first and deal with its own financing later is actually succeeding. While she no longer gives absolutely all of the proceeds from the sales of books to the artists in favour of a sustainable business model, Koyama Press is still committed to helping artists make as much money as they can. This means that in addition to printing books, Koyama Press also makes ephemera like stickers, T-shirts and pamphlets for each release.

“I like to have some supporting item for each book,” Koyama says. “It’s more of a way to promote the artist as well as the book. I’m not sure you can quantify that kind of thing but at least the artist can make a little extra.”

Koyama is humble but realistic about the press’s success, explaining that while she did come to publishing with no experience, she gained skills such as organizing people, managing budgets and problem solving as a former film producer. “As a former art student and avid reader, I’ve looked at a lot of art over the years and have developed my tastes based upon a few different preferences. I think that all of that came together here.”

Koyama is also deeply proud of what she has accomplished over the past five years. “Building something from the ground up that has brought attention to new and more established artists has been really rewarding. It’s what I had initially set out to do,” she says.

It only seems fitting that the indefatigable – and apparently invulnerable – Annie Koyama herself should also be turned into a comic book character. When developing a logo for Koyama Press, artist and character designer Aaron Leighton (whose debut book, Spirit City Toronto, was published by Koyama Press in 2010) came up with the tough, scowling, undeniably adorable character that now serves as the publisher’s mascot.

“Actually, it wasn’t initially supposed to be me,” Koyama explains. “Aaron is a talented illustrator and character designer and I really liked the character. For a while I only wore red, white and black and of course, the messy hair is familiar. My T-shirt printer Toby Yamamoto called her ‘Kickass Annie’ and it stuck.”

Kickass Annie by Hugh Langis

It wasn’t only Koyama and Yamamoto who were entranced by the design. Soon, other artists were providing their own rendition of the fire-breathing pixie. “Because it’s a good character, I can see the appeal in wanting to make other versions of her,” Koyama says. “Now, there are over 200 versions that people, not all of them artists, have contributed to the collection.” Many of these versions (including the three drawings by Hugh Langis, Aaron Costain and Michael Cho included here) can be found on the Koyama Press website’s Kickass Annie gallery. Some artists, like Dustin Harbin, have created entire comic strips about the character. Leighton notes that he is overjoyed by the ways that the character has been appropriated.

“I think both Annie and I were overwhelmed by the response the logo generated, specifically the way artists wanted to make it their own. So it’s been very cool to see Kickass Annie evolve, mutate and grow.”

The future for Annie Koyama, and Koyama Press, is a bright one, despite the difficulties that plague most of the publishing industry. Annie is still able to handpick the artists that she works with and produce books that are as physically beautiful as they are conceptually sound. This variety and quality is reflected in Koyama Press’ spring season, which includes work as disparate as Everything Takes Forever by Manhattan-based illustrator Victor Kerlow, whose dryly witty, often politically charged work has appeared in the New York Times and The Believer; and the Journal by Montreal-based artists Julie Delporte, whose work is characterized by quiet, interior intimacy.

This variety gives Koyama Press its strength but also prevents its aesthetic or artistic mandate from being easily definable. “It’s difficult to nail Koyama Press books down to one single aesthetic, because Anne publishes such a wide range of material; Michael Comeau, Steve Wolfhard and Julie Delporte all seem a thousand miles away from each other, in both style and content,” says artist Michael DeForge who has published three volumes of Lose and his forthcoming book Very Casual with Koyama Press. Despite the difficulty, DeForge took a stab at defining the press’ aesthetic, saying that many of the artists Koyama publishes “come from illustration or animation backgrounds, and have a different set of influences and techniques than artists who work more exclusively in comics would.”

Annie Koyama also chooses books with subjects she believes are particularly worthwhile, such as good autobiographical stories, non-linear narratives, children’s stories, and LGBT-friendly work, all featuring beautiful artwork in different styles or photography of urban settings. In other words, the press is defined by a selectivity that would seem impossible for many presses but that is second nature to Koyama.

While Koyama Press is thriving in the notoriously challenging industry of print publishing, it has thus far avoided venturing too deeply into the realm of web comics. “I am not rushing into the digital realm until I’m satisfied that the resolution is good enough to do justice to the artwork,” says Koyama, whose preference for print comics has also played a hand in the way she approaches digital content. The press does maintain an active website and Tumblr, which frequently features short comics and updates on forthcoming titles (such as recent proofs of DeForge’s Very Casual).

Part of Koyama’s affinity for the printed object may come from her own artistic impulses, which she is almost too shy to talk about. “I’d like to try my hand at painting again one day when I have more time,” she admits, “but aside from doodling on paper, I leave that to the artists. I used to do things like papermaking, collage and book binding so I guess I’ve always liked paper up close.” The physical materiality of the print object still holds a special draw for Koyama.

Like most superheroes, Koyama is reserved when talking about her own accomplishments and ebullient in her praise of those she works with. Many of the artists she’s worked with, however, are more than willing to go on record agreeing that Koyama is an indie comic superhero in every sense. Leighton says working with Koyama Press has nothing but positive effects on the lives and careers of artists and notes that the impact ranges from “the boost of having one’s work recognized and published for the first time to some of her artists becoming international comic celebrities.”

“She is absolutely a superhero,” agrees DeForge. “She took a chance on me, and provided me with opportunities that have really changed my life.”

It’s a rare few who enjoy a career so defined by love, and one thing that comes across keenly in every conversation, every interview, is the absolute love that Koyama has for what she is doing. When asked about what makes her career, with all its risks, unlikeliness and strangeness worthwhile, she has a clear answer: “The pure joy of discovering really exciting work by emerging artists. And of course, seeing others appreciate that work in a book, zine, print or show that you had a hand in is pretty satisfying.” bp

Natalie Zina Walschots gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council’s Writers’ Reserve Program.

Interesting stuff, I re-designed my site and then the serps

plummeted

Broken Pencil Magazine Blog Archive Kicking Ass and Changing Games –

The latest addition to my weekly read