Tensions are mounting in Indonesia. An increasingly conservative atmosphere has forced once vibrant sub-cultures to go further underground. Ideological lines between pluralists and radical Islamists have hardened. Vigilante abuse and media campaigns target LGBTQ2S+ people who don’t lay low.

Organized groups against queerness have grown rapidly since the early 2000s, advocating for political and structural legal changes that criminalize homosexuality and constrict the movement of transgender individuals.

“The Supreme Court failed to pass a law making homosexuality illegal [only] because the council member who brought forth the proposition was arrested for corruption,” says Ais, laughing at the fragile luck. Such chaos of culture and state too often characterizes the world’s fourth most populous country. But amidst it all, the artist and amateur historian has helped build an intrepid oasis, burgeoned by thick walls of zines and queer pasts: the Queer Indonesia Archive.

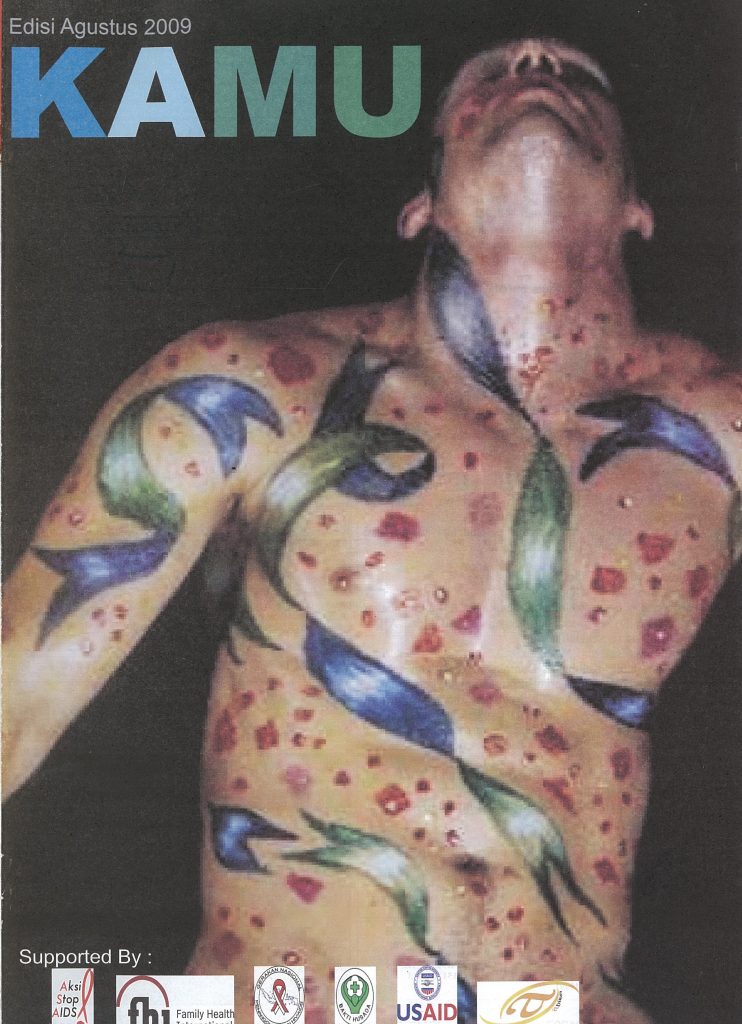

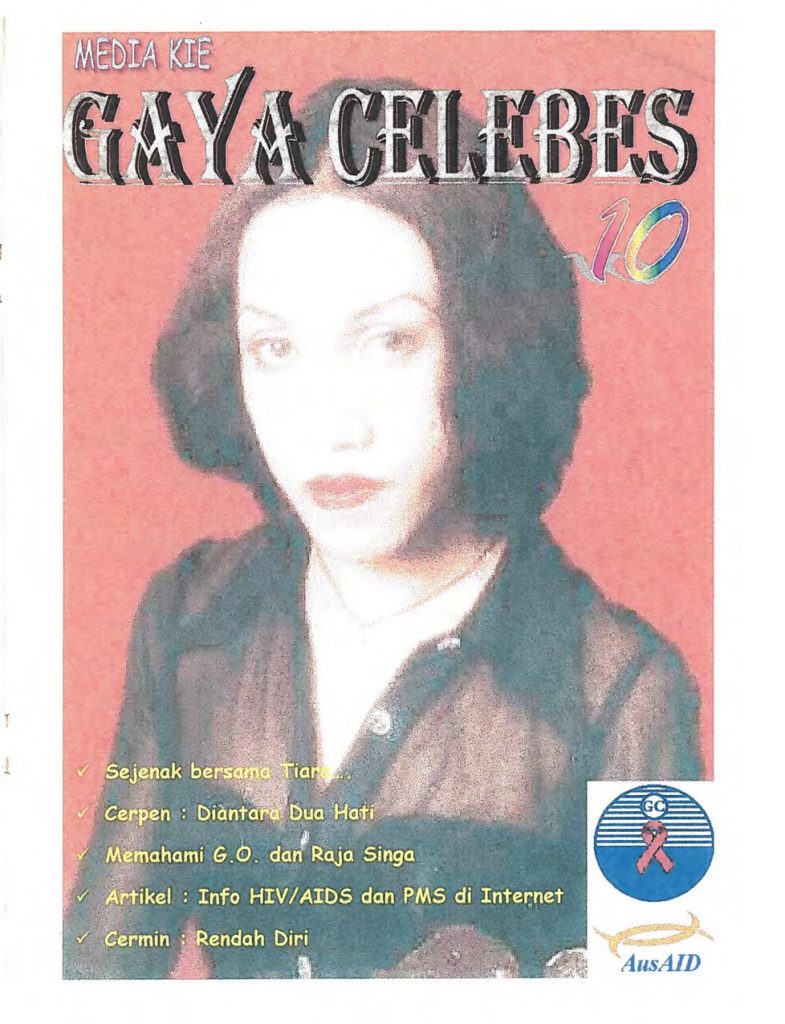

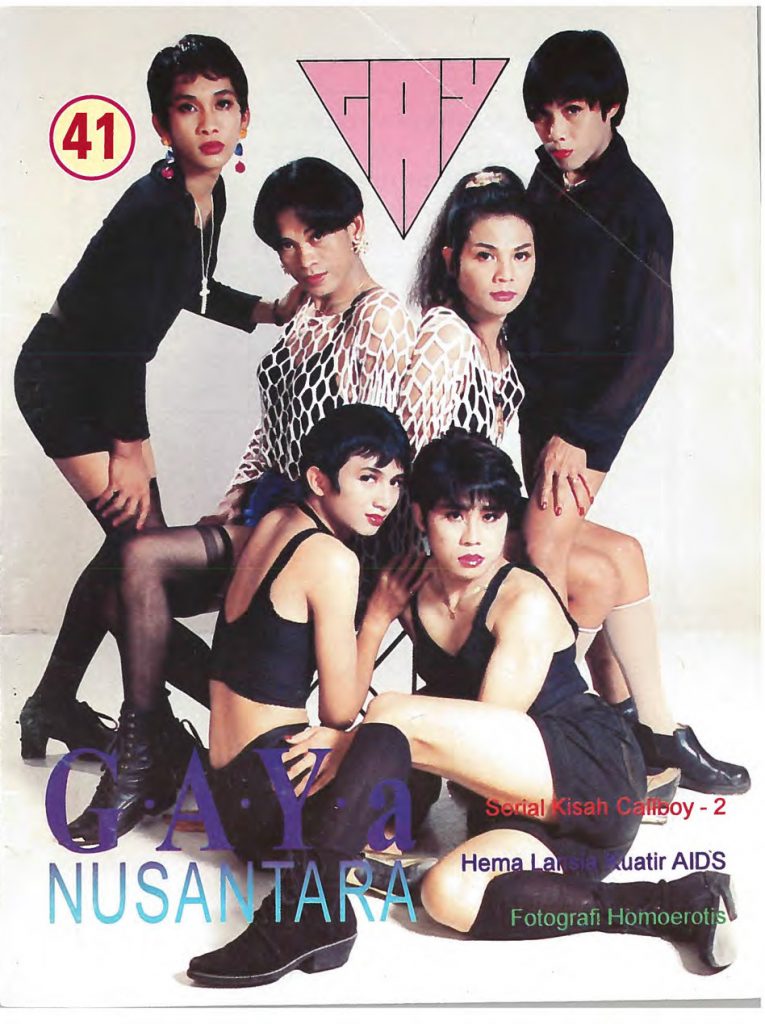

The project, as of now, is an open-ended digital library that features decades of zines, ephemera and documentation from LGBTQ+ creators in Indonesia. The items and publications are organized into collections surrounding places, periods, people, and issues.

It is endlessly explorable, and equally complex. The project makes no illusion about the fierce persecution facing queer and trans communities, and at times, its shadow looms large.

But that is only part of the context here. QIA is also celebratory, defiant. These texts and images teem with records of creative resilience and play, diverting the conversation about queerness in Indonesia away from revolving around the threat of violence. Instead, QIA offers a space that champions self-determination, visibility, and remembrance. Pretty daring.

“There is space for the debate of queerness, as well as [to] argue for the rights of the LGBT+ community and fight against intolerance,” explains Beau, an Australian activist and amateur archivist. He helped co-found QIA alongside Ais. Beau describes a “polarity” between the country’s vibrant and diverse queer cultures and a looming, growing prejudice.

Indonesia’s dense and political zine scene has long provided a platform for a booming counterculture, including a distinct queer streak. In the archive you’ll find stories of queer joy, pain, festivity, surprise, and romance, documenting a vivid history of the LGBTQ+ zine culture that has existed in Indonesia since the 80s. The intensifying oppression has only added urgency, not fear, around the need to preserve collective memory, say Beau and Ais. The pair are untrained as archivists, but nod to the strong DIY subcultures they cherish as they develop the project.

Meanwhile, the future of the zine movement remains somewhat unclear to Ais as well. Today’s “queer youth are less prone to share their work,” he observes. This is compounded by the comfort and efficiency of the internet, of course.

So what’s inside? Scrolling through the site, I find tender perzines, scrappy poetry, and short stories, a few even in English. These are punctuated by bright and amateurish illustrations and comics. I look at these and I imagine their impact in its original era, how wide of a reach it had to expand the inclusion of the community beyond Indonesia’s borders. I’m thinking how thrilling the camaraderie between readers must have been as it unfolded, and realize that here, with me, it continues to unfold.

One charming recurring feature is a section for personal ads tucked in the nooks and crannies of the zines. Today, these have evolved into online dating profiles, hemmed in by grids, swipes and app-specific gimmicks, but at the peak of analog, there were few templates to contain the format. Instead, these pages spill in an intimate patchwork of lingering email addresses, lists of hobbies, and stats about appearance, age, height, education, occupation, overflowing with both aesthetic spunk and profound longing.

In MitraS #2, a personal ad from a queer writer in Jakarta reads “I am very glad if U write me, anybody!” Another from the Indonesian diaspora in Australia “would like to hear from you for friendship!” An overarching enthusiasm can be measured by the dozens of exclamation points.

When I ask about these, Ais and Beau are quick to remind me that any correspondence made as a result of these ads would have needed to be sent via secret P.O. boxes that zinesters at the time discreetly maintained.

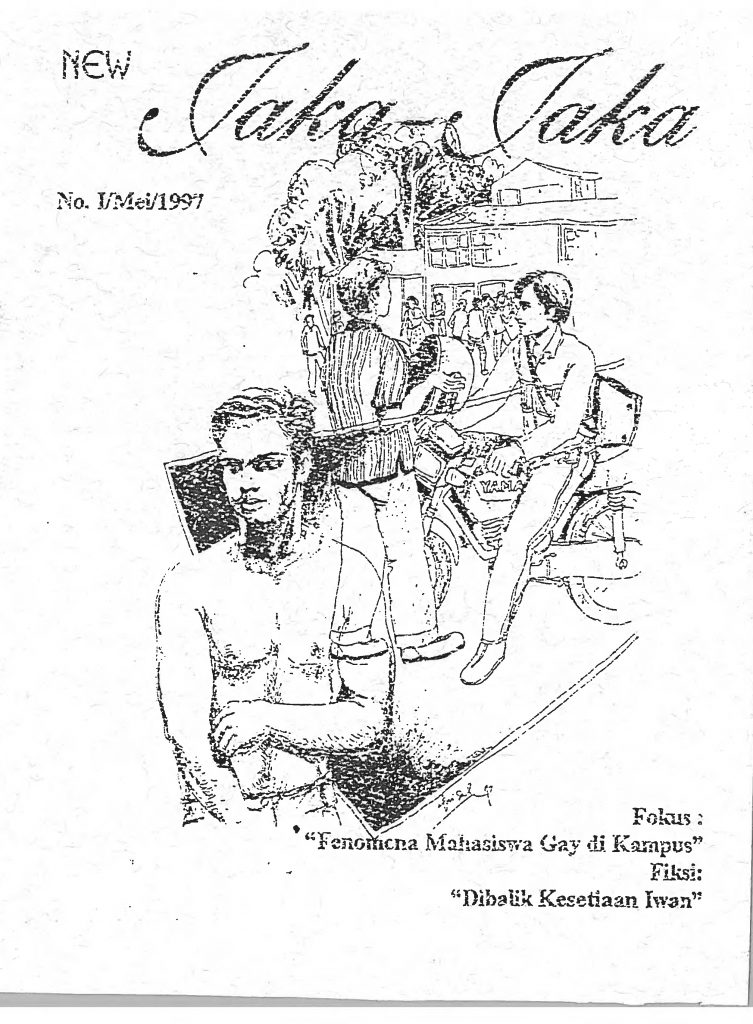

Also in the archive is New Jaka-Jaka Issue #1, which includes a romance story entitled “Dibalik Kesetiaan Iwan” or “Behind Iwan’s Loyalty.” It’s hard to grasp, as I translate line by line, but I squeeze out feelings of loss and regret. Scrolling further, I unknowingly “stumbled” into an erotica, also translated loosely to make sense of the pages. These pieces are charged with ardour and devotion, the self-awareness of being both a lifeline and a message in a bottle.

The survival and revival of these zines, themselves, are a testament to the strength of the independent press in facilitating and advocating space for communities to thrive even amid environments that deem them taboo. Disrupting, if discreetly, intolerance in its many forms and over generations, the archive is alive, and its possibilities continue to surface.

The QIA project can be found at qiarchive.org.