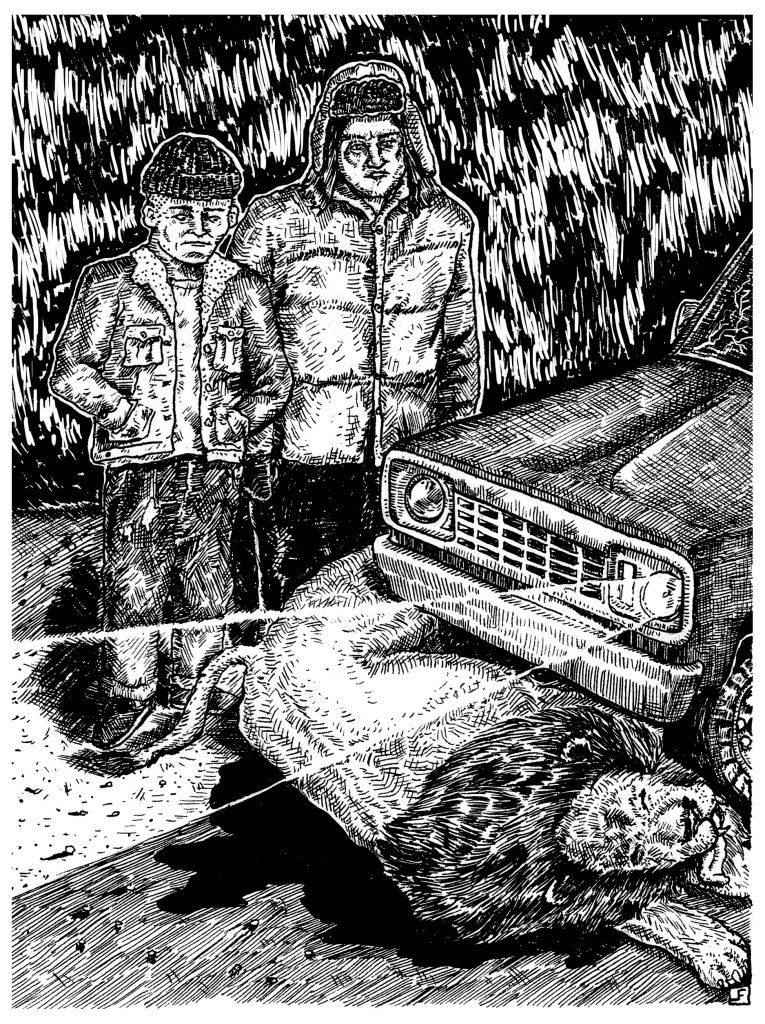

illustration by Joe Frontel

Andrew F. Sullivan’s Twitter bio describes him as “Canada’s Gentle Brutalist” and that’s pretty much right. His writing is dark and unrelenting but beating through it all is a tremendous heart. His debut book of short stories All We Want Is Everything came out in 2013 from ARP Books. I clicked right away with Sullivan’s surreal hardboiled darkness and couldn’t wait to read more – and luckily, I didn’t have to wait long.

I caught up with Sullivan shortly before the publication of his first novel Waste, now available from Dzanc Books. Waste takes place in the fictional city of Larkhill, Ontario; a town full of abandoned factories, rotting houses and desperate people living life right on the edge. Co-workers Jamie and Moses are driving home one night when they hit and kill a lion. They flee the scene, back into their own personal hellscapes of meat, mayhem and murder: fractured families, skinheads, druggies and bodies in barrels. There’s a man who owned that lion, though– and unfortunately for Jamie and Moses, that man isn’t the forgiving type.

Waste is a dark, relentless book – the prose stripped down, the characters kicking and screaming towards the conclusion. But, just as in real life, there are moments of unexpected humour. Sullivan punches straight through the CanLit Rainbow and then stomps on the pieces. He’s forging his own path and you’d be wise to walk with him.

AGP: Right at the beginning of Waste, there’s a line: “Don’t start thinking there’s a light at the end of this bleak-ass tunnel.’ (Laughter) You tell the reader straight up: “This is how it’s going to be, guys.”

AFS: Yeah. I really don’t think fiction has a responsibility for redemption or hope or anything like that. I think that’s a very Canadian feeling to have – like there has to be some reflection or restoration – and I don’t necessarily agree with that. I’m not interested in being redemptive.

AGP: With that being said, a large part of this book is really about family, and the failure of a lot of family dynamics, and trying to find a substitution for that.

AFS: Family is an ongoing and evolving thing. You can’t write about characters who don’t have parents. I think a lot of first books start that way. It’s always an orphan. Moses isn’t like that but his entire life is structured by his father leaving and the degradation of his mother’s mental state. Trying to find a substitute for family– I think that’s where a lot of hate groups come from. Even when it’s wrong, it’s still something.

AGP: (With these characters) you really get that sense that they’re all a product of this decaying community, the rotted hotels, the shuttered factories.

AFS: Yeah. I didn’t write it to be a perfectly realistic book. It’s hyper-real. I think that’s the way we like to see our home towns, with this epic scope. Even in this book– yes, it is

incredibly violent, yes, a lot of bad things happen. But really, one dude gets shot. Other people kill themselves, or get thrown into a TV, or–

AGP: Get their kneecaps drilled.

AFS: Or get a bowling ball to the head. But in the end, this isn’t like a crazy spree. I think part of that is what makes it more violent in some ways, is that killing someone without a gun is difficult. And it does stick with you. It does leave residue.

AGP: Have you heard from anyone else from Oshawa about the book?

AFS: No one from there has said: ‘What the hell?’ But I’m sure people will. Larkhill is not purely Oshawa. It’s London, Ontario, it’s Peterborough, it’s Sudbury– it’s its own place.

AGP: Are there any true stories in this book?

AFS: There’s a lot of heresay. And urban legends. And stories about a guy who knows a guy who did a thing. There’s no stand-in people, exactly. I don’t really write that way. I don’t write

about people in my life.

AGP: That’s one thing I like about your writing, actually. You can tell it’s not, “Hey, this happened to me on Thursday and I just wrote it down and changed the characters and now it’s fiction.”

AFS: I think a lot of contemporary younger writers do that because they don’t really know what else to do. Or they’ve only gone to school for writing. I mean, a lot of it did come from

me. I did work in a warehouse. But did all that stuff happen to me? No. (laughter) I did research. I read the police blotter from 1980 to 1989 in the Oshawa papers. I did condense it all into four days– baseball bats being thrown out windows, guy being burnt alive in a strip mall, guy being stung to death by bumblebees– a lot of these things did happen.

AGP: I don’t want to say Waste is a hard read because it’s very readable. But it is very dark. I’ve had people tell me, “Write happy endings because that’s what sells.” Did you ever get that?

AFS: Oh yeah. All the time. This book had a lot of problems: “No hope, no humanity, borderline nihilistic…” I don’t think it’s nihilistic at all. I just think it’s about consequences.

AGP: Moses and the skinheads talk about building something of their own. That’s not a nihilistic idea. They’re going about it in a terrible way but it’s a hopeful thought.

AFS: They are trying to find a code or a meaning in their life. They’re doing it the wrong way but that’s not nihilism.

AGP: What draws you to the darker side of narrative?

AFS: I end up there because I think things go wrong. It’s an interest in our capacity to take pain and failure and make it into something new.

AGP: How did the book end up in the hands of a U.S. publisher?

AFS: A mentor of mine, Jeff Parker, said Dzanc does a lot of good work – you should send it there. It was after the Canadian (publishers) had said this is too dark, this is too nihilistic. I’m not writing off Canada or anything like that. But yeah, we ended up going to the States. They still thought the book was pretty fucked up, but they also thought it was funny. Which is what I had hoped for. Even things that are tragic can still be kind of funny. And then you feel even worse, and that’s kind of what I want. For someone to laugh and then go, ‘Oh shit, wait, he’s serious.’ Even when something silly or funny happens, there are still consequences.

AGP: Like getting your teeth knocked out. There are so many teeth scenes in this book.

AFS: I have a paranoia of facial injuries. Eyes and mouth. When you talk about violence, it’s stuff to the face that is memorable. I think teeth say a lot about social status.

AGP: This isn’t a horror book in terms of genre, but there’s a lot of horrific stuff and a lot of body horror.

AFS: I love body horror! To me, this is FUBAR meets The Brood. Shitkickers and evil snowsuit children and bodies betraying people.

AGP: Tendon surgery, pimply ingrown hairs, heads bashed in, knees drilled, bubbling burns… I could continue.

AFS: Exactly. You could go on for pages. (Laughter) I do like writing about the body. The body is vivid and alive. But alive isn’t always positive. Alive means pain and growth and those kind of things. I think body horror is connected to time and failure. So much is not in your control. Trying to make people morally culpable for their bodies is wrong.

AGP: What are you working on now?

AFS: I have a short story collection. It’s pretty long and it’s weirder. It’s about alien tractor beams and nightmare hotlines and stuff.

AGP: Sold!

AFS: It’s called One Moon Feeds Another. We’ll see what happens with it. And there’s a novel about human trafficking in Hamilton called Earth Filled With Blood. It’s based on a heavy metal flood of aluminum and other heavy metals that turned the countryside red. I’m starting to sketch out a book about trying to sell houses that people have been murdered in.

AGP: More light-hearted stuff.

AFS: That’s the thing. I’m not going to change what I’m doing. It’s weirdo body horror, slightly violent, viscous… very wet.

Waste launches at the Garrison in Toronto on Wednesday March 23.

A.G. Pasquella is an Associate Fiction Editor at Broken Pencil. His short fiction has been published in McSweeney’s, Little Brother Magazine and Imaginarium 2013: The Best Canadian Speculative Writing. His latest novel is The This and The That.