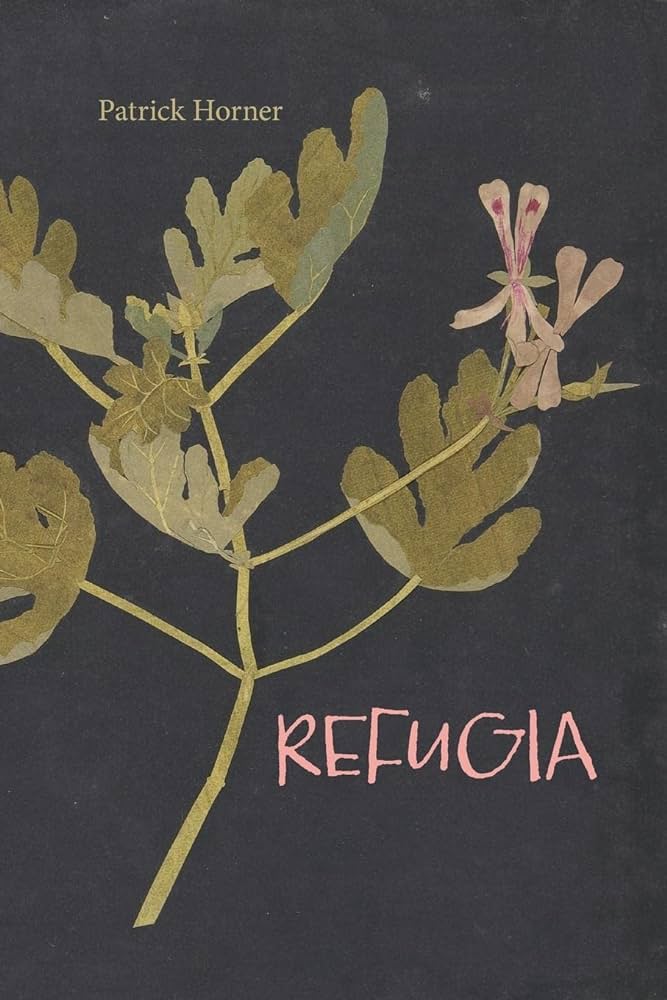

Refugia

Patrick Horner, 136 pgs, University of Calgary Press, press.ucalgary.ca, $24.99

Beginning in Victoria in 1965 and working backwards through a missing persons case, Patrick Horner’s new poetry collection uses “found evidence” of prose poems and letters to tell the story of two biological anthropologists researching rare specimens on a remote archipelago.

Told in fragmented, rapidly oscillating points of view, Refugia muses on the insufficiencies of language in the face of a vast and unexplainable island. One researcher struggles throughout the collection with how to properly communicate the incommunicable. Roland con-fuses time as he writes to his future self as a ghost of the past in short, feverish reports trying to accurately record and describe its resplendence.

In contrast, Emily employs a frustratingly academic, but usually fascinating blend of scientific jargon and romantic sentiment. Her narration is occasion-ally grotesque, but not for its own sake. Her sections are somewhat obtrusive, and her scientific terms tend to go over my little literary head, but the shared instinct to quantify the unquantifiable shines through. Together they experience a slow descent into willful insanity in the island’s isolation.

Horner plays with the nature of voice and who exactly gets to speak. Bear and Mouse are specimens the biologists are studying who can communicate with each other through metaphysical letters about the nature of nature and their own observations of the humans. Together, they reveal truths about nature as some great human equalizer in their animal reality. “Words are more important when we want to take something with us,” and they don’t need to take a thing. Even though they are dead, it takes far longer for them to diminish.

Later, the narration takes on more spiritual undertones to describe more surreal experiences. Because of their solitude, our narrators have some difficulty figuring out what is real, and thus so does the reader. As we go on, we realize just how unimportant an adequate description of their surroundings is to absorb — as insufficient language may be — the depth and shared consciousness of the natural world.