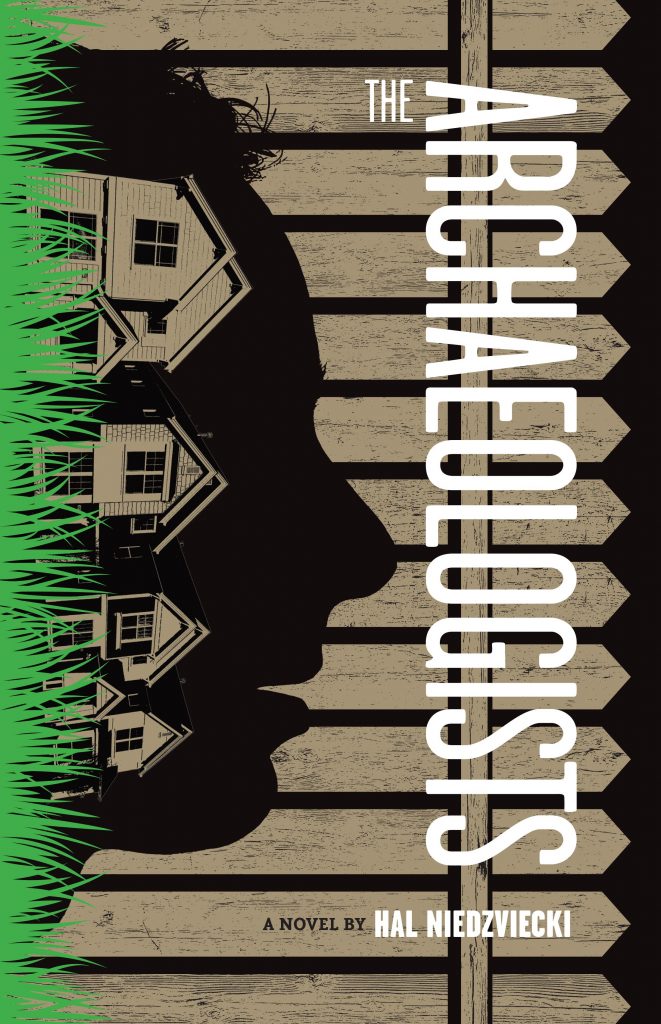

This chapter is part of the ongoing serialization of The Archaeologists, the new novel by Hal Niedzviecki to be published by ARP Books in Fall 2016. The Archaeologists is being serialized in its entirety from April to October with chapters appearing on a rotating basis on the websites of five great magazines. To see the schedule with links to previous/upcoming chapters and find out more, please click HERE.

1. Tim—Thursday, April 10

Tim stands legs apart, arms akimbo, on the steep muddy embankment. The grass beneath his boots is long and stringy. It sticks to the seeping earth. His neck cranes up and back as he reconsiders his decision to climb down the hill into the river valley. He can just see the battered car at rest in the clearing above. He shifts his gaze to the dark basin below him. This causes his body to tense, his muscles to realign. He feels the worn bottom of his right boot beginning to slip. His gangly legs slowly spread. Tim tries to adjust his stance, but instead he loses balance altogether. He falls backward and finds himself half scrabbling half sliding down the hill. He picks up speed, bouncing over all manner of sharp, foreign objects, detritus from the make-out spot above: crushed cans, burger boxes, wet toilet paper wads, a cell phone with its circuit board guts exposed. Tim’s boot heels dig in. Mud furrows. He grabs at bush ends and wet branches. Finally, he arrives, not quite tumbling, at the soft bottom of the ravine.

He climbs to his feet. He brushes himself off. Wet mud cakes the rear of his pants. Uncool. Who’s gonna see me down here? Still…Tim scans the crest of the hill. There’s nobody around, but he feels like he’s being watched. Uncool. Reflexively, Tim pats down his pockets. Lighter. Check. Car keys. Check. Wallet. Check. The letter—

Shit. Where’s the letter? Carly says he’s always losing things. She says he needs to be more organized. Yeah, he admits sheepishly, I’m working on it.

Tim rams his hand into his army jacket pocket. He feels it—folded paper gone soft and greasy. He thinks about pulling it out, scanning those words again, as if there might be something else in the barely legible pen scrawl, something he missed the first forty times he read it. The letter arrived more than a month ago. Tim hasn’t shown it to Carly. He knows what she would say: that he should forgive him, go see him, hug him, help him. Carly’s parents, almost but not quite retirees, live in a bungalow in the northern part of the city. They call and visit and ask questions. They hover over her. She’s their only child. Their special little girl. It’s easy for Carly to envision him forgiving, even forgetting. Tim sees it too—like a movie, actors filling in the cracks that real life just seems to widen. The letter uses words he could never imagine his father saying out loud: regret, forgive, sorry. Sorry? Sure you are, Dad. But let’s get to the heart of the thing. Tim feels it, a sucking hunger in his chest. The soft wet oh so deep empty heart of the thing. Sorry about what?

Tim walks. The gully of the ravine isn’t as impenetrable as it looked from the clearing above. It’s the opposite, in fact: branches point to suggestive clearings and last summer’s leaves carpet accidental footpaths. Tim plows through scraggly shrubs and bare-limbed trees. The ravine feels entombed, dead to the world. This is just a quick pit stop, Tim reminds himself, a quick look at his old hideout. He’ll smoke a joint and calm the nerves. Then he’ll go and see for himself if it’s not too late, if he can put the past behind him. He hasn’t seen his father in almost twelve years. He doesn’t want anything from him. He’s worked in bars for almost as long as he lived in what he once stupidly thought of as home. He’s a high school dropout. He’s a bit of a stoner. He has a girlfriend.

—Carly.

He’ll call her after. He’ll tell her the whole story: the way the letter arrived out of nowhere; the way he kept reading and re-reading it, words circling restlessly round and round his skull like old Evil Knievel getting ready, one more stunt, nothing left to lose. I’m dying. Cancer. I’m sorry. Tim’s sorry too. Sorry he didn’t call or text or at least leave a note. Instead, he carefully folded up the letter and stowed it in his back pocket, searched for her car keys and his wallet from the coffee table clutter, slowly pulled on his boots, and marched out of the apartment, a man with a plan. Tim stops walking. The river gurgles. He can’t see it through the rustling underbrush. There are birds and squirrels. He notices, for the first time, how loud it is. He hears heavy breathing—his own—and the sound of sweat dropping off his nose and splashing onto moss, roots, dirt, whatever else is mouldering away underneath the trees, the names of which Tim doesn’t know. It’s better that way; knowing would just make the whole thing louder. All those elms, pines, alders, firs and maples demanding they be paid attention to.

He thought it would be quiet in the forest. His ears are still buzzed from the drive, from the rattle of Carly’s twelve-year-old Pontiac, rusted orange hand-me-down from her mom lurching past the speed limit, past the outer suburbs, past the short ribbon of yellow farmlands squeezed between an ever-expanding grey zone of housing developments and accompanying mini-malls. Tim’s dad always drove big black sedans, a new one every six months. Carly’s car sports a tinny cassette radio. Tim had turned it up as loud as it would go, Bob Marley blasting…don’t worry…Tim lit a joint, veered slightly to the left, responded to an indignant honk with an equally indignant middle finger. Then he toked. The interior of the Sunfire filled with smoke. Tim cranked down his window and highway air poured in. Carly did not like him lighting up in the car. The car rides he used to take with his father had been still, sepulchral, the air thick with cigar and cologne. His dad’s Cadillacs moved smoothly ahead as if they were drifting just above the pavement; and no matter how fast the scenery outside sped by, his little boy self stayed lost, enveloped by a succession of slick, cavernous, black back seats.

He’s a big boy now. A grown-up. Sort of. He urges himself forward. He feels his heart pumping against his ribs. When was the last Tim walked farther than the corner store? He’s a cab man.

Tim struggles on through the spring mush. He follows the river, keeps the river in sight. This much he knows for sure: the spot he’s looking for—his spot—is near but not right on the bank of the river. Which he can see now, flowing slowly by like a giant contiguous wad of chewing tobacco effluvium. Smells like it too, he thinks.

Tim tilts his head, looks up. Through the branches he sees tiny patches of grey-smudged sky. The sky seems close and also far away. He can just make out the upper floors of the houses on the ridge. He’s trapped down here. Tim breathes deep into his abdomen. It’s cool. He’s cool. Once upon a time, he lived in one of those houses. Almost there, he thinks. He’s just going to find his old spot. No biggie. He’s not trapped. He can leave anytime. Just turn around and go. Carly says he has problems finishing things. Carly says he has to finish what he starts. So: Plan’s a plan—right Carly? That’s the way his father used to talk: Plan’s a Plan. Use It or Lose It. Smoke ’Em If Ya Got ’Em. Tim hears his father’s voice, contemptuous and impatient: What plan ya idiot? You call this a goddam plan?

Tim closes his eyes. He’s trying to visualize, to see how this is going to go. How it’s all going to work out.

Relax. Close your eyes.

That’s one of Carly’s things. Inner peace. Or something.

Behind his eyelids, Tim sees naked trees, possible paths, scrubby bushes, everything the same brown-on-grey camouflage.

Tim opens his eyes. He feels calmer, not calm, exactly, but less like he’s trying to breathe hot sticky molasses. His slack calves itch. His forehead pulses. The worst are his long skinny legs, knees wobbling from all that humping over fallen forest, thighs burning from the sheer effort of self-propulsion. Still, he wills himself forward. The sun comes out, late afternoon dappling of faint warmth through the interlocking overhang of branches, like hugging Carly in her thick winter sweater. Skin underneath. Tim’s on the final bend of the river’s S curve, feeling dizzy from the constancy of rounding motion.

He stumbles past and doesn’t notice.

But he stops anyway.

He’s ten feet from the riverbank. Between him and the escarpment sits a large rock, almost a boulder, jutting out of the earth. There’s a cluster of weedy birch trees so tall and thin they actually manage to sway in the breeze. There’s a hole in the ground, more like an indentation, the earth slightly darker, scarred—

The fire pit! How could he forget the fire pit?

It’s all in the details: the fire pit, the birch grove. He forgot about those. It comes back to him now, not in one mad dash for the mimetic finish line but in starts and stutters. Synapses slowed by time or, perhaps, by a certain degree of overindulgence in what his dealer Clay always calls—with just a hint of proprietorial pride—the product. And then there’s the tree, the giant oak that forms a triangle with the boulder and the birch grove, the fire pit sitting in the middle of Tim’s boyhood territory. The tree. Not, as might be reasonable to assume, smaller than Tim remembers it, but actually much bigger. He staggers over, puts a hand on the tree’s cool craggy exterior. Immediately he feels ridiculous.

Tim wipes his nose on the shoulder of his army jacket. He squats on his haunches and puts a finger in what remains of some crude hacks in the bark. He used to carve words into the tree, stream-of-conscious fragments from his addled teenage mind. His finger traces the outlines of a letter F. FUCKFACE, Tim says out loud. FUCKASS. FUCKWAD. Tim laughs. A heat in the pit of his stomach. Here it is. Proof. Proof of what? He’ll bring Carly here one day. He’ll show her the big rock and the even bigger tree, the scar in the forest floor where the fire pit used to be. They’ll stand there and neither of them will have to say anything. She’ll just get it.

He gazes up the long craggy spine of the tree. The steps are still there. Well, sort of. Some are rotting, some just barely dangling from ancient rusty nails. But at least half of the ten or so stairs leading up to the tree’s lower branches appear sturdy enough, orange nail-heads still visible buried in the dry dead planks.

The view from up there. That’s why he’s here. To see that view just one more time.

Tim leans back and stares at the dizzying vision of the treetop breaking out of the wooded ravine like a god looming over puny worshippers. Tree must be old. He’s never thought about it that way before—trees having an age. Tim can feel sweat cooling on his forehead. He shivers. It’s suddenly cold. Just get it over with, he thinks to himself. Or forget about it. He could leave, hike back up the muddy hill, slide into the frayed bucket seat of the Sunfire, light up a spliff and close his eyes. He doesn’t owe his father anything. He doesn’t owe anyone anything. Well, okay, he owes Clay around two grand and Carly eight hundred or so. But that’s a whole other issue. He pats down his pockets again. Car keys. Check. Pre-rolled joints. Yup. Che Guevara lighter. Present. And the letter. Tim fingers the ragged edge where the paper was ripped off a pad. I know you blame me for what happened.

Hal Niedzviecki is a writer of fiction and nonfiction exploring post-millennial life. This was an excerpt from The Archaeologists, to be published by ARP books in Fall 2016.

Hal Niedzviecki is a writer of fiction and nonfiction exploring post-millennial life. This was an excerpt from The Archaeologists, to be published by ARP books in Fall 2016.