The internet’s newest wave

of stylish shit-disturbers — the Cripple Punks —

are making noise about equality and accessibility in the scene

by Sidney Drmay

What is Cripple Punk?

Plug the term into Google and you’ll see an explosion of hits: people taking Instagram-style selfies with their walkers and canes in full view, confessional text posts about doctor’s appointments, blogs dispensing advice on dealing with new pain medications and photos of canes painted with blue polka dots and tentacles.

This is the essence of cripple punk: an uncensored, unapologetic look into the lives of disabled people who are tired of being your pity porn.

Kat Mokus is a 23-year-old college student from Oshawa, Ontario who lives with several long-standing chronic pain injuries as well as cognitive and mental health issues as a result of a car accident. Mokus, who is gendervoid, was one of the first self-identified cripple punks (or “cpunks”) to post pictures of solidarity. In one of their early photos, they stand grinning under a lilac bush with a patched-up vest, a bright pumpkin-orange shirt and their walker.

Kat Mokus (disabledfemme.tumblr.com)

Mokus has used self-portrait as self-care since they were very young — long before the #selfie trend permeated the world’s lexicon. “Cripple punk was a phrase I’d been trying to embody and live long before it was coined. It helps with my identity integrity issues,” they say. “The first cripple punk pictures I posted were definitely because I desperately needed community around me and I needed other people to see me and connect with me.”

Mokus wasn’t the only one. Cpunks like Jill Blaze, otherwise known as floppy-unicorn on Tumblr, stare down the camera sporting striped tights, a black dress and disheveled hair, showing off their wheelchair and killer style with equal aplomb. Eighteen-year-old Beth (whatbethsays) hails from Australia. In one photo, she flips off the camera with a disgusted look while showing an arm with congenital disorder, or in plainer terms, an arm that stops just past the elbow.

Annie (annielaineydoesfashion) is a 24-year-old lesbian from Florida. Scroll through Annie’s Tumblr page and you’ll see her posing in her wheelchair in a blue cheetah print top and mirrored sunglasses. Her outfit of the day is highlighted with black leather gloves and the cheetah print foot hammock at the base of her wheelchair: a recent addition to give her leg rest more style. All of these cpunks are united under the same banner of pride.

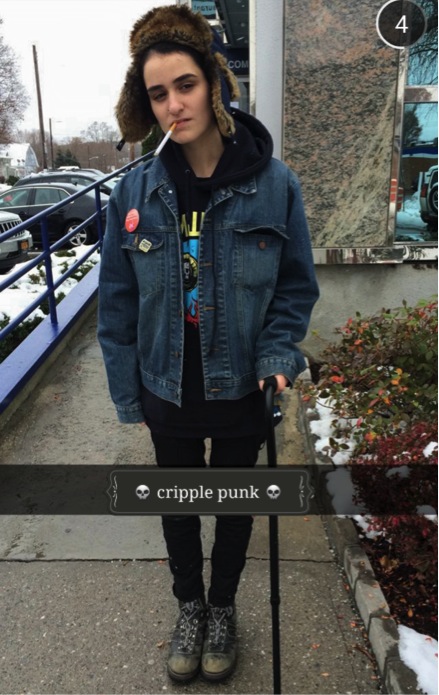

The movement started with Tyler T., known as ffsshh on Tumblr. In an early Tumblr photo, they stood in a jean jacket and band hoodie, tight black skinny jeans cuffed over their scuffed-up combat boots. They leaned on their black cane and a cigarette dangled from their scowling lips. Tyler, who is nonbinary, didn’t intend for the picture to get much attention.

“I made this post [the picture] because I was dealing with a lot of internalized ableism around getting a cane and wanted to feel empowered,” they say.

Ableism is the discrimination or prejudice against people with disabilities, and takes many forms — whether it’s intentional or not.

In the case of Tyler’s photo, the backlash from able-bodied users towards was a perfect example of ableism: commenters believed they had the right to assume that Tyler’s smoking and their disability were somehow related and judged them accordingly. Tyler received a series of messages claiming that if Tyler “didn’t smoke [they] wouldn’t need that cane”, that being handicapped was not something to be proud of, and that there was no sympathy “for cripples who make themselves worse”.

“If you really cared about disabled people, you wouldn’t cherry-pick the ‘good ones’,” Tyler wrote back.

Jill Blaze (floppy-unicorn.tumblr.com)

Other disabled individuals began posting their own photos in solidarity with Tyler, posing with their mobility equipment and displaying their physical disabilities with the hashtag #cripple punk. Since the original photo was posted, an online community has formed for those who are disabled and want a space to speak freely about their disabilities on their own terms. More and more disabled people have found and identified with cripple punk, joining the movement and finding friends and support within it.

“It’s affected my daily life in a few major ways: the first being my confidence,” Tyler says. “I have cripple punk to turn to now when internalized ableism comes up for me and knowing that makes me feel a lot better. It makes me feel powerful and like I have something behind me. It’s a lot easier to not feel ashamed now.”

Of course, cripple punk — like any other subculture — comes with its own set of complications. Avery is a 17-year-old Black member of the cpunk community who identifies as trans. Their first cpunk post shows them staring down the mirror, hand raised in a “rock on” gesture, their curly Mohawk dyed bright green. Their knee and ankle braces are clearly shown: in the caption under the photo, they lament about how their new glittery combat boots don’t fit over their braces. It’s a great photo, but it’s also impossible to ignore the fact that they’re one of the few Black people represented by the “cpunk” tag on Tumblr.

“Like a good deal of Tumblr movements, it is (unintentionally) a bit white-centric,” they say. “I sometimes feel like I’m the only Black cpunk in the tag, which is probably not correct. I do see Latinx and Asian people pop up in the tag every so often, but I think it would be great if we could get even more POC in on this movement. It’s important for true intersectionality.”

They, along with others in the movement, remain hesitant about the use of the term “cripple” as a descriptor.

“I don’t use it outside of talking about cpunk,” they explain. “I’ve had that term directed at me many times, though it was probably not meant to hurt me as much as it did. Overall, I feel that if reclaiming the slur makes an individual feel more powerful, than they are welcome to. For those who aren’t comfortable with it, there’s the recognized, slur-free ‘cpunk’ abbreviation that’s there for them to use.”

Kat says that cripple punk fits with their own ideal surrounding punk culture on a whole. They started getting into punk music around Grade 8, and these days, they listen to everything from the Offspring and The Creepshow to more politically-oriented groups like G.L.O.S.S. and Bikini Kill. Like all punk fans, this early discovery has permanently coloured their belief systems and values. “My love of punk music is totally centered around banding together with other marginalized folx and resisting the system,” they say. “My disability puts me in yet another marginalized category of people who are usually forgotten and mistreated.”

Annie (annielaineydoesfashion.tumblr.com)

Punk shows are often advertised with the guidelines of “no racist, classist, sexist, homophobic or transphobic behaviour” at the bottom of the show posters or Facebook invites, and yet there is rarely a focus on the ableism within the community. Those who are physically disabled cannot always participate in a mosh pit for risk of irritating old injuries or causing new ones. There may not be any place for people to sit and still see the band, while smaller DIY basement shows often lack ramps or staircase elevators.

“My first experience with an inaccessible venue space was hearing of a show going on in my hometown of Oshawa two years after my disability onset,” Kat says. “This venue was on the top of another venue with a long, steep staircase that I knew people often rushed, pushed and bumped up and down very quickly. I knew that I could not bring my rollator, and even if I could, I would not know how to ask someone to help me get inside. So I gave up on going to the show.”

“I want shows in venues that are wheelchair accessible, I want show posters with accessibility information shown clearly,” they add. “I want to feel welcomed in that environment that I had previously felt welcomed in [punk shows] and I wanted to make that space available for other people.”

Greg Benedetto is a 30-year-old punk from Toronto who books shows and plays in the band S.H.I.T. His most recent DIY venue, S.H.I.B.G.I.B’S. recently closed (located in a downstairs basement venue, it was not accessible). He continues to book and promote punk shows in other venues across the city. Benedetto says he “rarely” gets accessibility requests when planning shows. “Most people who ask, ask about an event being age-accessible before asking about it being physically accessible,” he says. He says this is not because accessibility isn’t taken into consideration but that not all accessible spaces are suitable to certain shows. “Currently, Toronto has two accessible venues with gender-neutral washrooms — The Garrison and D-Beatstro,” he says. “A good number of other venues we might use — Silver Dollar, Coalition, Smiling Buddha, The Horseshoe Tavern etc — have a variety of issues, be it stairs to the entrance, stairs to the washroom etc. Depending on the size and requirements of a show, and the availability of spaces, we’ll always aim for a venue that is age-accessible and physically accessible but given how few there are, it is not always possible.”

This is something Sean Gray is fighting with the website Is This Venue Accessible (iTVAccessible.com). The site documents which music venues throughout the U.S. are accessible for people with disabilities, including volunteer efforts and crowd-sourced information from users to provide detailed breakdowns of venue features like stairs, bathrooms, doorway widths, and overall practicality in getting around. (See Sean’s advice on setting up accessible venues in his sidebar to his article.)

“Punk music and music venues should be way more accessible to disabled folks and especially queers of colour and Indigenous queers,” Kat says. “If punk is so rebellious, why can’t we rebel against the inaccessibility of the world and work to create venues which are accessible for wheelchairs, have seats for resting, and support scent-free environments?”

This is likely the true definition of a cripple punk: someone who refuses to be stopped, refuses to be put in a box and rebels against the ableism that is consistent in our society and spaces, even those that claim to be accessible to all

“I am a disabled punk. I am a disabled femme,” says Kat. “And I am more proud than ever to be a cripple punk.”

READ MORE: Is Your Venue Accessible?

Many of the individuals featured in this story prefer to use only their first names and tumblr handles because of experiences with harassment, discrimination, and not being “out” to their families/employers.

Sidney Drmay is a white, queer, nonbinary cripple punk from Toronto. They like cats, activism and sour keys. You can find them on Twitter @webspookie.

Kat Mokus’ “Disabled Femme” patch is available for purchase at etsy.com/ca/shop/disabledfemme along with many other awesome cpunk patches, art and zines!