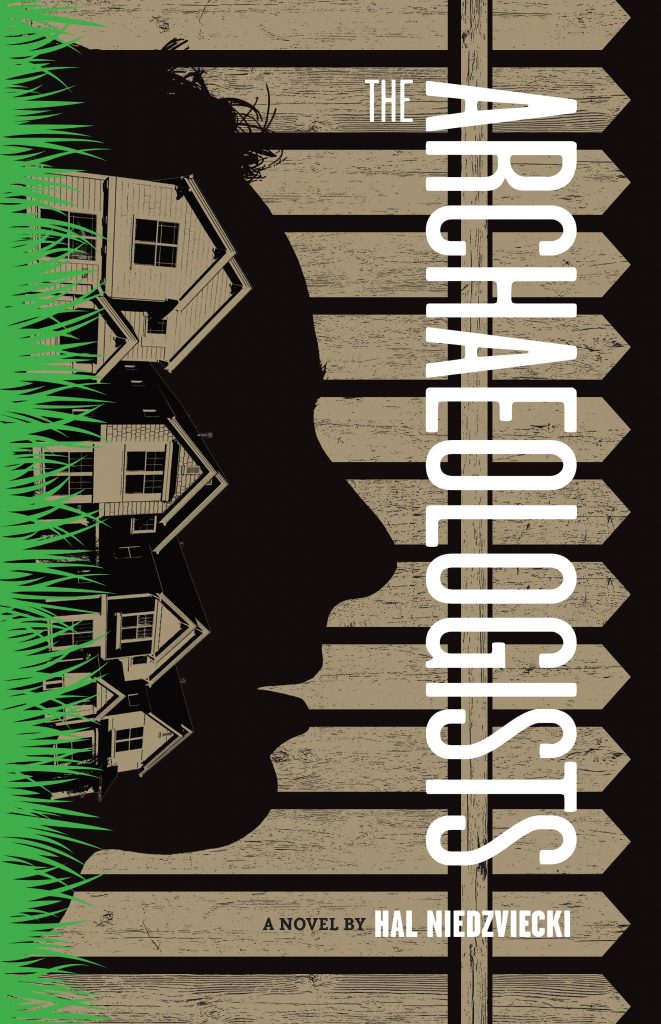

This chapter is part of the ongoing serialization of The Archaeologists, the new novel by Hal Niedzviecki to be published by ARP Books in Fall 2016. The Archaeologists is being serialized in its entirety from April to October with chapters appearing on a rotating basis on the websites of five great magazines. To see the schedule with links to previous/upcoming chapters and find out more, please click HERE.

6. June—Friday, April 11

6. June—Friday, April 11

Great big street going North. Hurontarion, artery to the highway. Other roads are capillaries winding through the flesh of the edge city. Cars penetrate like blood, coating subdivisions, new developments, bare fields promising communities named after absent trees and elusive glimpses of the river.

Hurontarion is three lanes each way, traffic bumping and grinding in a striptease of progress. 18-wheelers, minivans, SUVs, even the occasional car trolls the congested laneway seeking access to the Save-A-Centre grocery store, the Next Future Shop, the Bed, Bath and Yonder, huge stores leading up to the biggest attraction of them all: the Middle Mall.

June sees a gap in traffic. She speeds up. She’s alert to the ebb and flow, the way the cars surge and recede, the way life itself seems to stall, then shoot forward. She can feel it now. How everything can matter, how even a trip to the grocery store can be—real. She just needs to stop thinking so much. That’s the problem, that’s what it comes down to. She’s spending too much time alone in an empty house. It’s amazing how easy it is to get lost in your own head.

June signals her turn into the grocery store. She’s out of it now. She’s back. Last night—

it was like a dream. But it wasn’t a dream. Whatever else it was, it really happened. She can still feel the rough grain of the heavy shovel against her palms. Her forearms ache, muscles pulsing. Maybe that’s all she needed. Something physical. Something actual.

When she worked at Phfizon all the employees got a fitness rebate of up to $300 a year. She joined a gym for the first time in her life and came to enjoy it. StairMaster and treadmill, she stepped along, going nowhere fast, feeling the sweat drip down her inner arms, involuntarily picturing the crisp files stacked up on her desk, each one marked Confidential in red, important letters. Sample size, she would think with each panted stride, co-morbidity, clinical trial, generalizability, patient response, efficacy, pregnancy. But gradually, her head cleared of pharma jargon. Then, back at work, everything would flow: she would find herself clearly, even artfully, building the text for the brochure the reps needed to promote their new cholesterol-lowering drug to physicians. She and Norm were just starting to date. She was learning on the job, speaking up in meetings, joining her co-workers in company-sponsored picnics and bowling outings. Then, all of a sudden, it was gone. Despite a 1.3 billion-dollar annual profit, she was abruptly downsized, her position one of several thousand identified as more efficiently performed by outsourced contractors, overseas freelancers, she later learned, doing the writing she did for pennies per word.

June makes the turn into the grocery store parking lot and pulls into an empty spot. She stretches her arms above her head, feeling her sore muscles. She bears no ill will toward whoever ended up getting the work. They have to eat too. Only—it had been a grim time. She’d had no inkling, no warning. Her performance review had been stellar. She’d bought a bike and started to cycle to work, peddling silently through side streets misted with early morning frost, soon to be dispelled by the sun’s slow rise. Ancient history, June tells herself. She’ll get a bike here, she decides. She’ll join a gym. She’ll get back to figuring it out. Whatever it is.

June releases her seatbelt, which snags on her bulky sweatshirt. She’s in sweats and jeans; she didn’t even take a shower. She just wanted to get out of the house, breathe the air, fresh and cold after the storm, move, keep moving. Now she feels clunky. She could have at least gotten properly dressed. Norm bought her a cute workout jacket from lululemon for her birthday. That was three months ago. It still has the tags on it. I should have—Why? So she can look good for the Save-A-Centre cashier? This time of the day she won’t even get the pimpled high school version. One of those used-up ladies, bad dye job, sour-faced. Dump your change on the counter and make you pick up the coins one at a time so they don’t have to touch your pretty palm. Sighing aggrievedly, June swings herself out of the car.

June pushes her cart down aisle nine looking for those crackers Norman likes. She’s already rolled through snack foods. Not there. Why not there? They keep them somewhere else, in some other section—“organic” or “ethnic” or “party planning” or “gourmet.” She scans the shelves.

June? Juney?!!

June turns, sweatshirt heavy on her shoulders.

Christine?

Christine looks sharp, looks like a woman, like a grown up. Her hair in a glistening brown bob, cream silk blouse offsetting a black skirt and jacket number that reveals long legs, always, June recalls, the girl’s best asset.

What a surprise! June abruptly exclaims, forcing her face into an enthusiastic grimace.

I knoooow, Christine giggles. I haven’t seen you in ages! How are you?

I’m fine, I’m great. June smoothes at the crown of greasy honey brown ringlets escaping her fraying ponytail. How are you?

Wow! Christine says. Look at you!

No! June says. Look at you!

June grips the handles of her cart, overloaded with bulk toilet paper, cases of Coke Zero and Canada Dry, ten-pack Save-A-Centre brand nutty nougat chocolate bars.

Christine puts down her mostly empty basket—mango, tub of lite yogurt—and plants her high heels in the middle of the aisle.

You live around here?

I—sure, we—live not far from here.

Wississauga Heights, Christine says.

That’s right. June smiles, keeps smiling. And you? You don’t—

I live downtown. Little Italy?

Sure. Yeah. Of course. It’s great to see you, Christine. Christy.

I go by Chris now.

Chris. Sure. June laughs nervously.

So, Christine says, her pupils narrowing in the bright track lighting. What are you up to these days?

I’m well, in between things…right now, I guess. I…got married. June holds up her ring finger and grins apologetically.

And it’s hard, of course, says Christine. With kids and everything.

Oh, June says. We don’t have kids. She follows Christine’s gaze to the jug of chocolate milk sweating in her cart.

I’m working on Bay Street, Christine says quickly. At South and Copperman. You know I went into law, right?

Sure, I heard that. June’s bunched cheeks are starting to hurt. Christine gazes at her expectantly.

So, uh, June says, what are you doing here in the ’burbs?

I was just on my way back to the city. I had to meet a client. Normally they come to my office, of course, but he’s an elderly gentleman, and he’s not doing so well, physically. Cancer, Christine faux whispers. Anyway, she resumes in her normal clipped tone, he’s revising his will. So I met with him, and then driving by I thought, it’s now or never. Who has the time to shop these days? I’m so busy—

As if on cue, Christine’s cell bleats.

Ah, excuse me, I just have to—

Listen, June says, great to see you. She awkwardly negotiates her cart around Christine.

Yes, Christine says impatiently, I did receive the file. She waves at June, bye or wait a second. In her lacquered fingernails a business card that June snatches as she squeezes past, catching a whiff of Christine’s tastefully elegant perfume. She hurries to the end of the aisle and steers the cart left toward the meats. Christine’s probably a vegetarian.

June in her baby blue sweatshirt. She pushes her greasy hair off her face and picks out a roast.

Hurontarion narrows, framed by a series of gas stations and family restaurants—Appletree’s, Taco Terrace—promising early bird family discounts. June hesitates at the turnoff, her foot wavering between gas and brake. Maybe she should just go home. Lie down. Have a nap.

But you cancelled last week—

And for the first time in months, June’s not tired. She dug and it rained and she dug some more, filling her shovel with the heavy, wet, cold earth. But she felt weightless, the shovel floating in her arms; she could have dug forever, the depression slowly and inexorably turning into a bottomless pit, her anonymity in the dark night underscored by the unshakeable conviction that she was being observed—no, not observed: watched. Then came a slight shift in the texture of the air, an early onset reminder of a coming grey dawn. Suddenly everything hurt, as if she was being forced to lift a load well beyond her means. Gripping the shovel, she had stared into the hole she’d dug and saw it: her true burden—an astonishing discovery.

June accelerates. She’s sticking to the plan. Make the rounds at the home, then head to her home and prepare dinner. She’ll dine with Norm on salmon-stuffed pinwheels matched to a highly recommended unoaked South African chardonnay. The curtains will be kept closed.

Nothing to see. Nothing to see out there.

And tomorrow, she’ll go to the garden centre. She’ll fill the dead space with a blooming jungle of—it doesn’t matter. Whatever grows. Whatever keeps Norm happy.

Fill it in. Cover it up. If it didn’t happen, it didn’t happen.

The short road to the home is easy to miss, more of an extended driveway than a road, really. It’s just off the main drag, but the low-slung building obscured by a thick row of hedges feels like somewhere else, somewhere far from anywhere. June arrives at the mostly empty parking lot adjoining the building and slows to a near idle. Weird pockets of emptiness are everywhere in Wississauga. They disturb her, these sudden moments of lapse, gaps in the sprawled city’s coverage. Finally she parks, carefully fitting the station wagon between painted white lines.

Temporarily permanent, Cartwright is home to eighty or so seniors. June’s assigned to the fourteen of them who live on the seventh floor. She brings cookies, offers tea, struggles with awkward minutes of conversation. She signed up in a fit of industriousness when she first moved to Wississauga. She told Norm she was considering going back to school, maybe social work, something to do with gerontology. Norm made appropriately encouraging noises.

June moves through the unstaffed, unadorned lobby and into a spacious elevator built for walkers and wheelchairs. The elevator dings and she steps out into the hall. The smell is of something spilled on the floor then haphazardly wiped up with a dirty mop dunked in vinegar. The nurses’ station is empty. June hurries past and knocks on the first door to the left.

Anonymous senior opens up. He peers at her suspiciously. Hi! she says with enthusiasm. It’s terrible, but June can’t remember the old fellow’s name. It doesn’t matter. Room 714 grudgingly takes a cookie from June’s proffered plastic plate. Mostly, they accept June’s ministrations as part of their daily routine. Even so, they’re as eager for her to arrive as they are for her to leave—their eyes half hooded, their TVs blaring, their days passing like the incessant sound of cruising cars one block over. They’re lonely, but not so lonely as to forget that June is part of a fleet of able-bodied intruders whose peering eyes are ever fixing on further evidence that grandpa has lost his mind, his hip, his sight, is no longer able to help himself, will never again work, drive a car, make love. Only one of June’s charges seems to actually be eager for her arrival, seems to be able to separate her from the conspiracies of a quasi-confinement marked by intermittent calls to bingo and bland institutional meals served up three times a day with a regularity designed expressly to mock the unpredictable bowels of the confined diners. June hurries through the other residents, saves Rose for last.

Rose it’s me! June finally gets to announce, opening the door without bothering to knock. Rose, unlike the other residents, doesn’t bother to lock her door. Rose says she has nothing to steal, and nothing anybody would want either. True enough, June thinks. A constant stream of cars passing, but nobody notices the seniors, even enough to bother to rob them.

Hi Rose. Sorry I’m a bit late…

Not to worry dear. You just come on in.

…traffic was terrible.

Gets worse every year dear. They say these days everyone’s got two cars. Two cars! Can you believe it? Rose’s voice, throaty and authoritative, makes June think of a chain-smoking high school girl’s softball coach.

Shall I make us some tea, Rose?

That would be delightful dear.

Alright then.

Feeling prim and vaguely nun-like, dear, June plugs in the kettle sitting on the counter of the kitchenette, really just a tiny space separated from the rest of the room by half a wall. It’s dark in the little unit. June squints down at the teacups, checking their cleanliness. Rose keeps everything murky, shades drawn, lights off except for one small tabletop lamp. She’s not quite blind, says she sees better with the lights off. June suspects she’s economizing on an electricity bill she doesn’t pay anymore, habitually saving money—for what? The future? Who knows? She could live another twenty years. June shudders. Somebody walking over my grave.

June bustles around making tea. Ritual. Calms us down, June thinks. She pictures Norman in the morning slurping his decaf coffee. Decaf, what’s the point? Ritual. Something to do. He didn’t notice that she was up all night, rummaging around the basement, waving a shovel around in the backyard in the rain. What was I doing? It was pouring out; and there was—

No—I just—

The back of her neck, cold—eyes on her.

Eyes.

No.

In the morning, she was there, beside him in the bed. She made him coffee. Toasted the last of a frozen bag of bagels. Nothing for lunch? he asked hopefully. I’m going shopping today, she told him. I promise.

Milk and four spoons of sugar. That’s how Rose likes it. Brownish sludge, sweet and sour. June unplugs the hissing kettle. That’s the extent of the cooking that happens in Rose’s kitchen. There’s no stove, not even a microwave or a toaster oven. At home they’ve gone state of the art, easy clean flattop electric that blooms a deep red with just the gentlest touch of a dial. But it’s better this way, June thinks. She can just imagine Rose immolating herself trying to produce the sort of thing nobody makes anymore—apple pie, meatloaf, gingerbread cookies.

No. Rose won’t be cooking any time soon. Her brittle fingers can barely hold the handle

of a teacup. Can’t cook. Can’t do anything, June thinks. Except stay alive.

Which she’s remarkably good at.

Rose’s body, pruned and stunted, has atrophied further than the majority of June’s antediluvian charges. But her mind is as sharp as her tongue. Charlatans, Rose announces. Liars and crooks. Rose’s favourite story. How she faced down the municipal planners and their corporate cohorts. In the end, they kicked her out anyway, built over what Rose describes as her lovely little cottage. It was just around the corner, there, dear, Rose likes to explain, waving her hand at the permanently curtained and closed window. June pictures a small shaded house, a once white panelled exterior yellowed from decades of exhaust. A little house sandwiched between a condo development and a Reno Depot. Rose refused to sell, wanted to live out the rest of her days in the house she grew up in. But her daughter, in her sixties and living on the other side of the country, cut a deal with the city and sent her packing. By now June’s heard the details at least five times: the moving truck carting away her furniture to god knows where, the ambulance they took her away in—I was healthier than they were dear! No matter how many times June’s heard the tale, she still feels disquieted by it. How could someone do that to their own mother? And how could the City let it happen? After all, Rose is something of a celebrity, the oldest person in Wississauga. As Rose tells it, they threw her out of home and hearth just days after she was shown on TV amiably chastising the mayor before cutting the cake to celebrate her 101st birthday. But, June supposes, it was for her own good. How could she have stayed there, all alone? Rose dismisses this argument. They were bringing me that Meals on Wheels! she announces indignantly. She prefers to talk about revenge. They stole it from me, she says. Rose says she’s not going to just wither away in some home while certain people live high on the hog at her expense.

June plunks tea bags into the chipped white pot adorned with—what else?—roses. Pot was pretty once, she’s sure, as were the many rose-themed dishes, knickknacks, and decorations that fill the small space. Rose was pretty too. June’s seen pictures.

Thank you, dear, Rose says as June puts a cup of hot tea on her the side table. Rose puckers her shrivelled lips and leans over a steaming cup to expel what air she’s mustered. The liquid barely swirls. Rose digs around for a cookie, prepares to dunk the hard disc into the hot brew. She doesn’t eat much anymore. A slice of bread, a cup of tea. She’s toothless, doesn’t bother with false teeth. At my age, she snaps, why be false? Rose tastes the cookie now. June can see the wet white dough stained dark brown slowly mashing between the old lady’s beige gums. June won’t let herself look away. The first time, feeling queasy as her stomach turned and Rose chewed, June got up to admire the corner display of dusty figurines, tiny pink-cheeked porcelain dolls, each one clutching a faded bouquet of roses.

Am I boring you dear? Rose had snapped. June flushed, spun back to attention. She’s taught herself, since, to watch in dispassionate awe.

Rose dips, gums, dips, gums.

June sips her still too-hot tea primly.

So my dear, Rose eventually says, my bones are a horror today. Damp out there, isn’t it?

Yes, June says. And it’s cold. It’s like it’s never going to be spring!

Rose makes a tssking sound. Terrible, the night. The damp. I can feel it in my bones. It’s all this rain we’ve been having.

It’s supposed to rain again tonight, June says.

Is it now? Rose leans down. She purses her lips and gasps over her steaming tea. Ah well, she says jauntily, no rest for the wicked.

Come on Rose, June says. You’re not wicked.

Then what am I doing in here? Rose emphatically gums a cookie. Dip and gum. Dip and gum. June hones in on brown crumbs sticking to the side of a face with the texture of a shrivelled prune.

Well, June finally says. It’ll be hot soon enough.

The heat nowadays! The summers! Terrible.

It’s hotter now?

Of course it is! My lord in heaven the heat these days! What do you people expect? They’ve done away with all the shade haven’t they? When I was a girl living just around the corner—again, the wave of a tiny shrivelled hand, teacup teetering precariously—there were trees lining the road on both sides, big trees, and the shade was wonderful. Just wonderful!

There were trees along the road? You mean…Hurontarion?

Of course, dear. Didn’t you hear me? Now it wasn’t called that, mind you, plain old Main Street was good enough for us back then.

How long ago was that, Rose?

There wasn’t much of a road, either. More of a track. Not like we have now. You risk your life just crossing now! Horses were more the thing back then. You barely ever saw a car come along.

Really? June sips her tea. She’s never thought of Wississauga as a place with horses. It just seems so present—a perpetually expanding now, a done deal of new roads, cul-de-sac developments, and strip malls.

Yes indeed. They finally had to widen the road when the factory up river expanded. My husband, Morton, he worked there. The Great Lakes Starch Company. Oh starch was in great demand back then, it certainly was. You were either a farmer or you were up at the starch plant. You could smell it for miles! But good for the town, you know, men have to make a living. Of course back then we were just good old Walletville. You couldn’t imagine what it would become. Dear me! I must be boring you right out of the room.

No, not at all, Rose!

The old woman scowls down at her tray. She considers the remaining cookie as if momentarily perplexed.

Sugar, June announces helpfully.

Eh? What’s that?

Sugar, Rose. It’s a sugar cookie.

Of course it is. Rose grabs the cookie in her claw and shakily lowers its exposed flank into her dun-coloured tea. Then she looks up at June: You’re a queer one, aren’t you?

June blushes. What does she mean?

Rose lifts mushy dripping sugar cookie to her toothless mouth. Her hand shakes as her lips purse in anticipation. Slowly, the mush becomes more mush as Rose gums triumphantly. Another day, another hour, another cookie squashed like a stray squirrel foolish enough to try to cross Hurontarion during rush hour.

Rose swallows. Closes her eyes.

Rose—?

Uh, Rose?

Rose lifts her sagging head, opens her eyes.

I’m still here!

I know, Rose. June laughs nervously. It feels damp in the building, despite the dry heated air seeping restlessly out of a centrally programmed furnace. June feels it in her bones. The damp. And the quiet, too. An all-encompassing silence if you transcribe the constant sound of cars hurtling past into a sort of muted wind.

Rose sips at her tea and makes a face.

My tea’s gone a bit cold, she says. Could you…

Back in the closet kitchen, June consults her watch. She’ll head home soon. Put a nice dinner together for Norm. He’s home at 6, everyday, on the dot. When you make your own hours, he always says, you never have to get stuck at the office.

Here’s your tea, Rose.

Lovely.

Rose lowers her mouth to her cup. June can see the moustache of greyish hairs on her upper lip. Draped in a faded nondescript nightdress and an unravelling cardigan, Rose’s body is formless. June imagines that nude Rose is nothing more than a head propped up by thin strips of gnarled joint dried out and ready to snap at any moment.

But Rose’s eyes pulse relentlessly. Milky blue, they see everything, seem capable of excursions into June’s yielding soul. The way the old lady looks at her, it’s as if, June thinks, Rose knows something, something about this place and June’s place in this place, something everybody else suspects, maybe even feels, but only Rose really and truly knows.

Now then, what were we saying dear?

I was wondering, Rose, if you remembered when they changed the name to Wississauga?

Dear me, that was some time ago. They opened that big mall around the same time. Biggest mall in the country, they said. I was at the opening, you know. Must have been…oh…let’s see now…1972? I would have been your age then.

No, June thinks. Older. Much older. Rose was already an old lady then. It’s incredible, how long she’s lived.

Of course I’d already lost my Morton.

They’d been through that on past visits. Tireless worker Morton who died in his 60s in the Sixties. It was the cancer, Rose told her. A cancer he surely got from his lifelong exposure to the chemicals that stewed in the bowels of Rose’s beloved Great Lakes Starch Factory. Amazingly, Rose still seems to miss him. Did he hold her at night? Dance her around their small living room like they were a couple at the ball? Did he make her feel like she was the only thing that mattered?

Now as I recall there was politics involved. Politicians! Terrible. You see several towns were being put together. Mashed into one big city. That’s what happened. And they said Walletville was a name from the past. They couldn’t name the new city after any of the old towns. Politics. A name from the past! Can you imagine? I guess I’m from the past too.

No Rose, June says feebly.

Rose waves a dismissive hand. Paper-thin, it barely swirls the dusted air.

Of course I am. There’s no need to lie to an old lady. It used to be just farms around here. Even the Indians used to farm up where that Country Club is now. Moved them off to god knows where. We used to walk to church, to school, the winters were terribly cold, the snow blowing up from the lake. We used to walk everywhere. There weren’t all these cars like there are now. All this driving around. Everyone’s from somewhere else, speaking who knows what language. The other day, some people knocked on my door, gave me quite a fright as you can imagine. A group of Chinamen going around talking about Jesus. I could barely understand them! Imagine, them telling me about Jesus! Now, dear, this must sound very old fashioned to you. But in my day, there wasn’t all this…mixing. You know, there was nothing wrong with good old Walletville. Rose lowers her face. Her shaking claw elevates her teacup two inches off the table. She pinches her lips and sucks.

I…June says. I’m not from here.

Of course you aren’t dear. Nobody is, anymore.

June isn’t sure what they’re talking about. She feels disappointed by this Rose. What is she saying? Is she…? No! Things were different back then, everyone was probably from…England or something. Rose doesn’t mean any harm. She’s just…stuck in another time, in the way it used to be. She’s leading up to something, June tells herself. Something that really matters. June can’t shake the sense that if she hangs around long enough, they’ll get to the present, to June, to the problems of a thirty-one-year-old suburban house wife, a queer one, sure, why not? The truth peeling away under Rose’s paint-thinner gaze. June looks down, looks at her watch surreptitiously. It’s getting late. But she doesn’t move. Tell her, she thinks suddenly. Just tell her.

Uh Rose? Her voice cracks as it comes out.

What is it dear?

I—uh—wanted to ask you something.

Yes dear?

I…

On the wall, a clown with a bouquet of pink roses, the garish oil still glistening under a layer of dust. When she dies they’ll sell it. Five dollars at a garage sale. Who gets the money? Who gets what Rose is going to leave behind?

Go on now, dear.

June exhales. Remember, Rose, you were talking about…the Indians?

The Indians, yes.

How they used to live around here?

Yes, of course they did. Didn’t I tell you that already? When I was a girl they had farms up where the Country Club is now. Then the government moved them off.

Where else did they live, Rose? I mean, before. Before they were at the golf course. Were 69

they living other places…?

What do you mean dear? They lived on their reservation, of course.

But before that Rose.

Before that? Well before that they just lived…everywhere.

But, do you know where Rose? I mean, did they have…villages?

Some things are even before my time, dear. I’m not that old.

Of course not, Rose.

And it’s not good to talk about it. The Indians.

Rose! Please!

Rose purses her lips, moistens them on the dark surface of the still steaming tea. Well, she finally intones, when I was girl we used to find old arrowheads and little bits of pottery down by the river.

The river?

Can’t you hear me dear? The Indians used to catch salmon there. That’s what they ate. My father told me that when he was a boy there were so many you could just reach in and grab one with your bare hands.

You mean…the Indians?

No dear! The salmon, of course.

In the river?

Well where else would the fish be?

How long ago was that, Rose?

Rose crinkles her furled face. She takes another teetering guzzle of tea.

Oh that was a long time ago now. We’d find all kinds of things down by the river. But we weren’t allowed to keep them. Oh no. They were cursed. 70

But that’s where they lived? By the river?

Well the Indians were moved off by the time the starch factory opened. And anyway that was the end of the fish in the river. But men have to make a living, now don’t they?

Yes Rose.

Now that’s enough of all this kind of talk. A bad business. What is it you were going to tell me?

I—

June takes a deep breath. A finger in her hair, twining a lustreless brown lock.

Rose I—

Now out with it! I don’t have all day you know! Rose laughs, pale pink gums and a withered stub of tongue.

Rose, I…keep feeling like…like there’s someone…in my house. Watching me.

What do you mean, dear?

I don’t know, Rose. I don’t mean someone. I mean, like, someone who—I know this sounds—but I keep getting this feeling…

Are you talking about a ghost, dear? The old lady looks her straight in the eye.

Do you believe in…ghosts, Rose?

Well I’m practically one myself, aren’t I?

Rose! Don’t say that!

Now then, there are all kinds of unfortunate spirits that walk the earth. May the good Lord Jesus claim their souls, dear.

Rose! You’re making fun of me!

Certainly not. I haven’t seen one myself, but when my great aunt Penny drowned after falling in the river, uncle Hamish used to see her once a year on her birthday. Because she went 71

before her time, she did. Now then, did you get a look at it?

It?

The ghost, dear. The en-tee-tee. Did you see the ghost of a dead Indian?

Rose! I don’t know if it’s—I mean, I didn’t, it wasn’t a…

Now just calm down, dear. I don’t mean to upset you.

You’re not upsetting me Rose! It’s just, I’m not even sure that—

It’s bad luck talking about it. The Indians are cursed. Doomed. And their bones are…

What Rose?

Angry, dear.

June gulps lukewarm tea. Liquid going cool. How long has she been sitting here? In Rose’s room, time seems to stop. Days pass, but no one notices. Nutty old lady with her Indians and her Chinamen. Jesus Christ Rose, it’s the twenty-first century. Now, at last, June feels exhausted. Last night. Digging. She couldn’t stop. She tore into the earth, threw huge clots of grass and dirt over her shoulder. She couldn’t control herself. Her muscles sit heavy on her as if thick blankets have been wrapped around her arms and legs. But the weird thing is, she likes it, likes the feeling, the weight in her submerged flesh. She wants to go deeper and deeper into the ground until she’s sunk under the firmament and disappeared into the truth, into what’s been there all along.

June finds herself on her feet. Her legs feel thickly substantial. Outside, the steady reverb of traffic heading to and from that giant mall next door. Rose is right. About what she saw. The hole in her backyard. That man, watching her. How could it be good? It’s—he’s—

Life, June thinks, inadvertently catching Rose’s pulsing blue eyes before quickly looking away. Life. Then death.

Since you’re up dear, could you make me another cup of tea?

Alright, Rose.

Hal Niedzviecki is a writer of fiction and nonfiction exploring post-millennial life. This was an excerpt from The Archaeologists, to be published by ARP books in Fall 2016.

Hal Niedzviecki is a writer of fiction and nonfiction exploring post-millennial life. This was an excerpt from The Archaeologists, to be published by ARP books in Fall 2016.