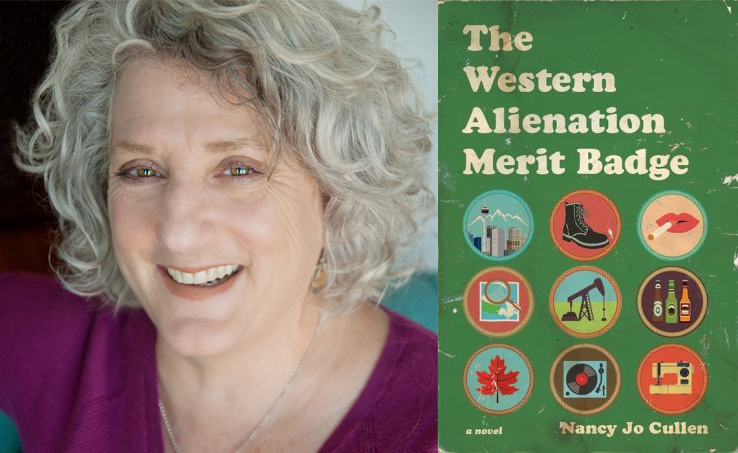

The Western Alienation Merit Badge

Nancy Jo Cullen, Wolsak & Wynn

It’s Calgary in 1982 and the federal government’s desire for energy nationalism is wreaking havoc on the finances of Frankie’s family. When she returns to help pay the rent and mourn the death of her stepmom, old tensions resurface and a final reckoning looms. This is the highly anticipated first novel from Nancy Jo Cullen who won the 2010 Writer’s Trust Dayne Ogilvie Prize for an emerging lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender writer.

The Western Alienation Merit Badge

is a part of our top Spring 2019 Indie Book Picks.

What inspired this work? In particular, the meditation on family dynamic, secrecy, and personal relationships?

Nancy Jo Cullen: I wanted to examine what could happen to a family that becomes unmoored by grief. And I was interested in the era of the National Energy Program, which continues to be sharply felt by many Albertans. There were definitely a few factors that led to a global recession in the early 80s, but the NEP made everything so much worse in Alberta. So I inserted the Murrays into that fraught point in time. The family’s first loss left them pretty disconnected so when they are reunited in 1982, it’s not so much that they have secrets but that they don’t know each other very well. And they are constrained not just by their economic reality but also by social/religious expectations, many of which we’ve shaken off some 30-plus years later, but which exerted another kind of pressure on the characters.

Can you speak to the direction and impact LGBT authors are having on the Canadian publishing landscape?

It’s very exciting to see LGBTQ writers getting some love from mainstream press and from prize juries. There is so much diversity and brilliance within this community of writers and I think readers who may have thought a LGBTQ book wasn’t something they wanted to read are picking up books and connecting with them. I hope this speaks to broader changes in publishing, that we are moving toward a more diverse publishing landscape and that readers and publishers are seeking out stories they might not have looked for in the past.

You’ve published a selection of short stories called Canary, as well as poetry in the past. How does writing longform fiction differ for you, and why do you feel it was best for this story?

Well, mostly I just had a moment where I thought: now I should write a novel, like it was some kind of a natural progression from short stories. And so I waded in. And honestly, I felt excruciated for much of the writing of the novel. Novels are so long and you have to leave so many bad pages unchanged until you finish your lousy first draft and then start again. What was I thinking? So, I don’t know that I began with thinking how this story was better suited to a long form. But, eventually, I began to appreciate the space that longform fiction gives the story. It allowed for little jumps in time and space, detours, if you will, that I don’t think work as well in shorter forms. Of course, there’s probably some writer out there proving me wrong right now.

How does the main character Frances Murray compare to her sister Bernadette? What is revealed about the complexity of feminine characters in the book? (Without giving too much away!)

Recognizing that three important characters in the book are female, I have to say that, when I was writing the novel, I was thinking less about the gender of my characters and more about how sibling relationships can be complicated by familiarity and lack of understanding that results in a kind of inability to see a sibling as a separate person entitled to the respect one might give to a friend or workmate. So the sisters end up in conflict that is certainly partly based on how each expresses her gender but also largely because they believe that as members of the same family, one should comply to an idea of family, whether that is extending acceptance, or conforming to expectations imposed by the church and wider culture.