If this were played on a stage now,/I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.

If this were played on a stage now,/I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.

-William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

Stratford street busker Matthew Murphy comes ready for a scrap. Long-haired, bearded, dressed in a poncho, he gazes angrily around the near-empty high Victorian courtroom. He is here to discuss his lawsuit, which, amongst other things, accuses a dog of a “crime against individual autonomy and a violation of his Charter of Rights and Freedoms.” It sounds preposterous, but a quick glance into the fiery eyes of the plaintiff and you know he means it.

If the summons raises eyebrows, the hearing itself is even more surreal. In a dramatic gesture appropriate to a town famous for its Shakespearean festival, Murphy brandishes a plastic grocery bag and pulls from within a crumpled copy of Chris Rickett’s What’s Up, Chuck?. The photocopied zine may look obscure to outsiders, but like most of Stratford’s political, legal and judicial establishment, it’s no secret to presiding judge Hugh McDonald. Over the past three years, the inflammatory monthly publication has had townsfolk in Stratford either laughing their asses off or, as Murphy illustrates in court, pulling their hair out.

Waving the copy in front of him, Murphy complains of being “subjected to ridicule and experiencing more than my fair share of shame, frustration and rage.” The source of Murphy’s “shame, frustration and rage” stems from the April, 2000 issue of Rickett’s zine, specifically a cover montage featuring ten unidentified participants mooning prospective readers. Apparently, Murphy’s butt was included in the “Whose is Whose Ass?” contest. The object was for readers to correctly match names to the buttocks on the cover of the zine, and win dinner-for-two at a local diner. Although a witness and affidavit swear differently, Murphy insists that he never gave informed consent. When the judge wonders how Rickett managed to shoot a posed photograph of Murphy with his pants around his ankles sans consent, the feisty busker threatens to subpoena everybody on the cover. Seeking damages in the amount of $4000 and a publication ban, he names as co-defendants Chris Rickett (editor) and Charmagne LaBrador, a Labrador retriever who serves as the magazine’s registered copyright owner. Rickett is respectfully dressed in suit and tie, but, much to Murphy’s chagrin, the dog is nowhere to be found. Judge McDonald accepts the pet’s absence, and Murphy is beside himself. “If I can’t serve a dog,” he stammers defiantly, “he shouldn’t be allowed to own anything!”

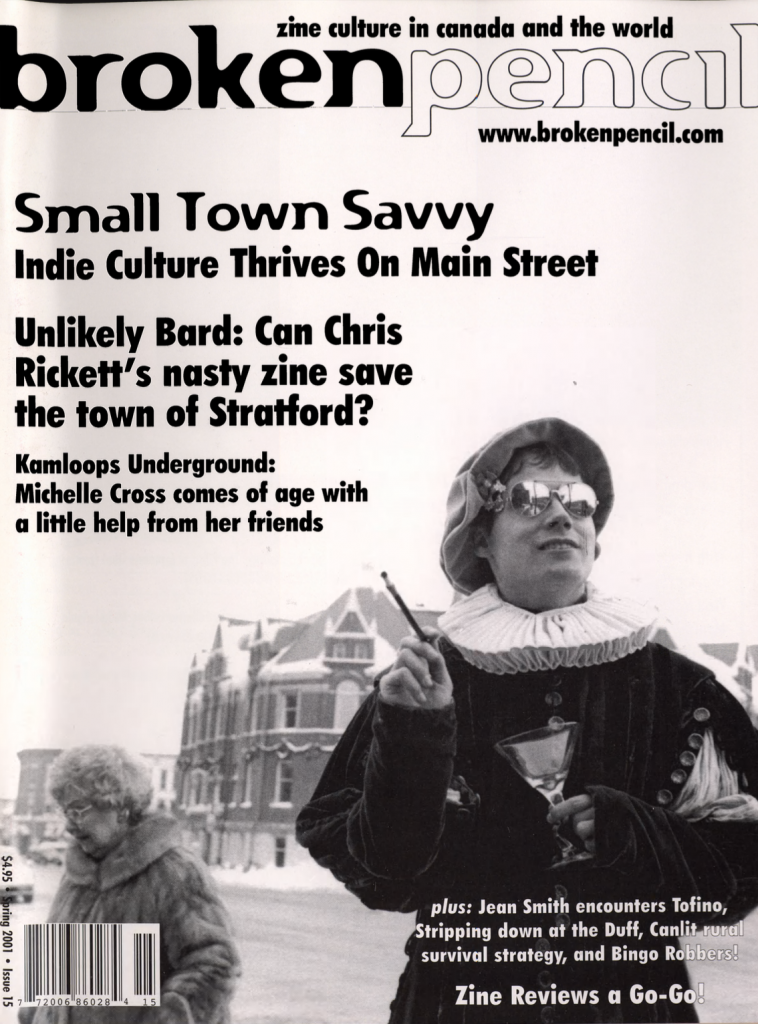

Stratford, Ontario’s resident bad-boy publisher Chris Rickett looks on impassively.

Equal parts Voltaire, Jane Jacobs, Hunter S. Thompson, Tom Green and Michael Verhoeven’s Nasty Girl, the spry twenty-three year old taxi-driver is something of a renaissance man. His many hats include magician, skateboarder, punk rock concert promoter, municipal activist, social critic, raconteur and publisher.

To most of Stratford’s elite however, he’s the spawn of Satan.

“I don’t think anyone has anything nice or positive to say about him or his magazine,” Dave Hunt, the town’s ex-Mayor (1988-2000), tells me over the phone. “This is a guy that’s gone out and bragged about getting young girls drunk and raping them, and about giving drugs to minors. I mean, this guy is really sick.”

At least Hunt is willing to go on record. Other members of the Stratford power structure are not nearly as forthcoming. New Mayor Janet Haslam refuses to even acknowledge that Rickett or his magazine exists. “I’m not in a position to talk to out-of-town press about a local situation,” she says disingenuously. “No comment.”

Perhaps that’s the inevitable consequence of pushing the envelope in a town like Stratford.

Situated between London and Kitchener in the corridor of southwestern Ontario, Stratford is, in many respects, a town like hundreds of others. Nestled up against Mennonite pastureland to the north and east, its traditional values are those of an agricultural community and small ‘c’-conservatism. In days gone by, the town was a hub for farming (it’s still home to the Ontario Pork Congress), and a manufacturing base comprised of furniture factories and small industry. The town was blessed with magnificent architecture in the homes and public buildings, but for the first half of the century the thing most outsiders could point at was its status as the hometown of Howie Morenz, hockey’s first great legend (though the ‘Stratford Streak’ was actually from nearby Mitchell).

All that changed it 1952, when journalist Tom Patterson created the Stratford Festival. The repertory theatre was an immediate success: In addition to the economic boon of all those tourist-thespians, the lure of high brow culture attracted a new population of artistes and wealthy professionals drawn to its charming downtown neighbourhoods. Half a century later, and the festival has transformed Stratford from a standard provincial town to a cultural landmark. How many other townspeople can boast that Obi Wan Kenobi, James T. Kirk and HAL-9000 once lived and worked in their humble burg? (Alec Guiness opened the festival in 1953 as Richard III, William Shatner spent three seasons there in the late 1950s, and Douglas Rain continues to live and work there.)

For all the benefits the festival has brought to Stratford, the town often appears to be suffering from a bipolar disorder. During the festival season, it’s not unusual to see the arts and croissant crowd sipping lattés on sidewalk patios, while 18-wheelers hauling pigs rumble past, belching diesel fumes in their faces. The downtown core is replete with elegant stores and restaurants – all of them full and the envy of every town in the province. But most locals neglect them in favour of ugly strip malls that line the town’s outskirts. With a population of 28,000, the town has the hesitancy of Don Cherry’s proverbial two-goal lead, not knowing whether to protect the cushion or keep going for more.

In spite of its contradictory nature, there’s one thing that remains steadfast in this community. Take the traditional conservatism of the past, add an economy reliant on public-image tourism, and Stratford is a town that’s scrubbed clean and doesn’t like airing its dirty laundry in public.

Which is where Chris Rickett and What’s Up, Chuck? come in.

Dear Mr. Rickett,

We received your ad copy and cheque for purchase of an ad in our school yearbook. I regret that we cannot accept your ad, based on what we know of your magazine. The goals of your magazine and those of our school yearbook are not compatible. Thank you for your interest.

Sincerely,

Bernard Gowand

Year Book Staff Advisor (Stratford Central)

It’s unlikely any publisher in the country, Conrad Black included, has a bigger and more visible profile in his hometown than Chris Rickett does in Stratford, Ontario. Whether they love the guy or think he’s a depraved asshole (the latter camp includes lots of loyal readers), the townspeople know him. When I first arrived in Stratford, teenagers on the steps of the public library were scratching their heads, unable to give me directions to Wellington Street, one of the downtown’s main avenues and home to the magazine. But when I asked them where to find Rickett’s headquarters, every one of them knew. The notoriety is equally apparent to anyone who shadows Rickett on his distribution run along the main drag, as I did later that same day. Store owners, housewives, septuagenarians…Stratfordites of all ages and backgrounds recognize and flag him down, requesting copies of the Chuck (the magazine’s common sobriquet around town) and speaking in hushed conspiratorial whispers about all the latest scandals.

Even ex-Mayor Hunt, who’s not exactly his biggest fan (“he’s not the sort of person I like to associate with”), concedes that Rickett and his zine have a huge profile. “Oh yes, there are people who are reading it,” he admits, “no doubt about it. Mind you, I’m certain some are reading it just to find out who he’s slandering next.”

The Stratford Police Department may well be readers in that category. Chuck‘s user-friendly investigative reports about Ecstasy abuse and headlines such as “Just Another Beating Courtesy of the Stratford Police Department” rarely win party favours from the boys in blue. But thanks to Rickett, police inspectors and constables have become household names through a litany of possible transgressions reported in the Chuck. And, no matter how much they may hate the thing, you can bet that the cops never miss an issue.

In fact, the police are such ardent readers of Chuck they’ve even paid visits to his advertisers and urged them to refrain from supporting the zine. “You can imagine the reaction,”

Rickett tells me at his office overlooking Stratford’s market square and within direct sight of the police station. “The police went around delivering letters from Inspector Jackson saying the magazine was trashing the reputation of the department.” Several advertisers felt intimidated enough to turn around and pay for notices in the daily Stratford Beacon-Herald apologizing to the community for having run ads in What’s Up, Chuck?. The few businesses brave enough to continue advertising in Rickett’s magazine often describe their donations as “protection money”, ostensibly meant to guard their establishments from Rickett’s slanderous wrath.

Other advertisers, such as Luke Sheepers, owner of the downtown Breadworks Bakery, simply believe that Chuck acts as a worthwhile mouthpiece to voice local concerns. A business owner with a stake in preserving Stratford’s quaint aura – “My business wouldn’t survive without the Festival,” he confesses – Sheepers is also a parent with children who’ll soon be teenagers. He admits to having received complaints from customers in the past about running ads in Chuck, but rejects the charge that Rickett’s magazine is a perverted and corrupting influence.

“It’s free speech,” he says. “I don’t agree with everything he prints, but I believe he has the right to print his views, which are certainly different from the coverage you get in the local newspaper. It’s funny, I look at some of the people who pick up theChuck, older people that you would not expect, and I try to figure out their reasons why. I imagine that many see his guerrilla writing as simply a youth venting his spleen, but he puts forth articles criticizing decisions that council makes about things they actually care about, like city workers coming in and cutting down their trees. Those are the kinds of things that really piss off home-owners that have paid lots of money to live on a nice street, and he’s writing about it.”

When Rickett started Chuck three years ago, he was operating a café for teenagers, trying to get a skateboard park built, and involved with the organizing committee for a Stratford Youth Council. He was also boldly preparing his first of two runs for municipal council, and created the magazine as a vehicle to get his ideas out. The name for the new publication was inspired by Chuck Dingman, the publisher of theBeacon-Herald (the last family-owned daily newspaper in Ontario until its recent sale to the Sun chain), as a poke at all the stories that Dingman’s newspaper wasn’t printing.

Having grown up in public on the pages of the Beacon Herald – from picketing skateboarding by-laws as a grade 7 student to running for town council – for Rickett to start his own publication seemed like a natural progression. A motto was chosen (“Tell the Truth and Run!”) and his mischievous nature inspired him to install his lawyer’s dog Charmagne as owner of Chuck‘s registered copyright. (Contributors retain copyright in exchange for walking the dog.) The original Chuck featured commentary pieces and works of fiction submitted by his buddies, but more than anything else, the zine focused on Rickett and his personal obsessions. Early issues contained numerous references to his predilection for drugs and juvenile pranks, as well as screeds against the town’s environmental degradation, police brutality, urban planning and sleazy political dealings. Citing the power of the pen, Rickett says the content was motivated by “breaking taboos and pissing people off for the sheer pleasure of watching their reactions at the moment their ideals are questioned.”

The profanity and references to drugs have been toned down since Chuck‘s beginnings, but the magazine is still pretty much the same. Distributed for free throughout the downtown on the first Friday of every month, the magazine is a 16-page photocopied and loose-bound publication that looks like any number of underground zines, with each of the 2000 copies meticulously collated and folded by Rickett’s hand. Similar in style to Frank magazine, every issue features caustic political rants, gonzo-style news reports, small-town gossip and innuendo, entertainment listings, comics and literature, and a controversial back-page column written by Harold Hibbs (a crusty old misogynist who lives in a retirement home).

One of the magazine’s most engaging regular features is Rickett’s monthly journal “Tales of a Festival City Hack,” which invites readers into his world as a cab driver. The occupation is one that fires his imagination, allowing him to receive tips and rumours from passengers. “It’s like a confessional on wheels,” he tells me. As an ingenious bonus, the taxi also provides an innovative distribution strategy as he and his fellow Radio Cab drivers get bundles of copies to circulate to fares and tourists.

Chuck’s unique mixture of local reporting and personality-tinged editorializing has managed to garner respect from some unlikely sources. Whereas Hunt maintains “the problem is that young kids are reading it,” Diana Loveless, the editorial page editor of the Beacon-Herald, reckons that’s not such a bad thing. “Most people think he’s an angry young man who rebels against things just for the sake of rebellion,” she says. “He does like to push the limits and test the status quo, but he has a real passion for Stratford. He engages young people in urban planning, he grew up here and doesn’t want to see it go the way of other small towns in Ontario.”

Nevertheless, like many others, Loveless also harbors reservations about Chuck‘s Jekyll and Hyde modus operandi. “On the one hand it’s an interesting mixture of lucid, well-thought out and researched ideas,” she explains. “He looks into municipal issues and probably digs deeper than we do on some things. He doesn’t worry too much, so he publishes things without having a lot of backup. If we wrote some of the same things, we’d probably get sued. But on the other hand, he does it by using a lot of radical ideas and not always in the most constructive way. He writes about the mayor and deputy mayor having homosexual relations in the washroom of City Hall. Maybe it’s true, I don’t know.”

That latter example is indicative of the most often-voiced complaint about the magazine – that Rickett’s gonzo-literary devices are routinely read by readers as literal truth. One reader going by the name JJ Baklava wrote critically: “Your purpose is sound, your methodology suspect… The underlying tone of youthful irresponsibility detracts from your otherwise commendable efforts… If you have any aspirations to public office you’ll simply have to compromise your baser indulgences in the interest of a better public face.”

Ontario’s former Lieutenant-Governor Lincoln Alexander told him much the same thing, pointing out bluntly that if Rickett wanted to get elected to town council, he would have to accept that a politician always hides his feelings behind a mask.

Rickett acknowledges some of the criticism thrown his way. “I’ve actually thought about prefacing some of the material with the disclaimer, ‘The following is a work of fiction’,” he says. But, ever relishing his status as a muckraker who relies on a unique blend of yarn and news to challenge the public’s indifference, so far no such disclaimer has been put in place. As a result, it is easy for Rickett’s detractors, such as ex-mayor Hunt, to use tongue-in-cheek articles — like the one about Rickett and his friends picking up out-of-town school girls at the Festival and getting them drunk and seducing them – as evidence of rape and substance abuse. A less ardent reader would conclude that Rickett’s narrative, centering on how he regularly strikes out with the women of Stratford, is in the vein of pathetic, comedic, fantasy.

Nick Giannakopoulos, a Stratford councillor for the past twelve years, acknowledges that Rickett’s dry sense of humour can get him into trouble, but Giannakopoulos is also surprisingly willing to defend the zinester:”If you read between the lines, he’s asking some really good questions. Over the last three years, we’ve seen people filling the council chambers and challenging decisions and becoming very vocal. Rickett informs people. He gives them the other side of the story and provides some balance with his point-of-view.”

“It’s no different from the Toronto Sun or the National Post,” Giannakopoulos continues. “Their editorial agendas are pretty transparent. They make no apologies, so why should he? And naturally, the establishment doesn’t like it. The Bronfman’s weren’t happy when newspapers reported they took 2-1/2 billion dollars out of the country without paying taxes. They were offended that it was disclosed in the national media… It’s the same thing as the reaction Chris is getting in Stratford to some of his columns.”

The prominent narrative of Chuck for most of the past year has been Rickett’s second campaign for municipal council, running on a platform aimed at fixing the environmental defilement and what he perceives to be the destruction of the town’s character. Like prosperous towns across Ontario, Stratford is under the constant threat of developers seeking to widen roads, pull down trees, and move box stores into the perimeter. Stratford also runs the particular risk of seeing the downtown exclusively inhabited by boutique stores geared at tourists and useless to the average citizen.

The question Rickett repeatedly asks is whether Stratford wants to preserve its unique small-town identity or become a neo-Mississaugan urban blight with all the amenities of a city. He’s emphatic that he’s not anti-development, but he believes Stratford can grow without having to sacrifice its character. His plan calls for preserving the downtown core by making it a public realm for pedestrians, not automobiles. He believes the mentality of Stratford is basically the same as everywhere else in Canada, caught in a consumer mind-set where growth is measured by mall openings and the number of cars in suburban driveways. According to Rickett, the public is shut out of the decision-making process and back-room deals that hide the cost of this kind of “progress”. In his second election campaign, Rickett said that if he got elected he’d address this problem by reporting in Chuck on the details of council’s in-camera sessions and secret meetings. As always, he ran his election campaign through the pages of the magazine and raised funds through a series of well attended wrestling matches and punk rock shows. He also utilized the ‘official press’, diligently knocking off a series of issue-driven opinion pieces in the Beacon-Herald.

“He writes great letters to the editor which make a lot of sense,” says Loveless. “He buries the offensive side you see in Chuck, and his are probably the best letters I put in the paper.” Giannakopoulos concurs: “The letters to the editor in the Beacon-Herald confirm his knowledge of basic principles and the community. I’ve always found his ideas of this community well formulated and he obviously knows a great deal about the history here.”

Indeed, the stories and signposts of Stratford’s past are never far from Rickett’s restless and inquiring mind. He tells me about a fight in the early 1970s when the town’s ornate city hall and a substantial part of the market square were slated for demolition. Developers planned to replace it with a white, ten-storey building topped with a revolving restaurant, in an area where there isn’t another building standing higher than four storeys. The chief instigator of the project was a councillor who, according to legend, stood on the steps of city hall and baited protesters by gleefully shouting, “the bulldozers are getting fired-up and ready to tear it down!”

The fiasco never saw fruition, but Rickett is adamant that warnings like that not go unheeded. “Stratford is a town with a history of going it alone,” he explains. “The Parks Board here fought against the corporate pressure of CPR a century ago when they wanted to secure prime real estate for another train line in the middle of town. If Canadian Pacific had got their way, we’d have a big rail yard where the Festival Theatre now sits, but the Parks Board preserved that green space for a greater good. The town used to be thinking long-term, but nowadays they’re rolling over and don’t aspire to anything greater.”

“Many of the people here don’t understand,” he continues. “Take the Festival…what makes it so special isn’t necessarily the quality of the theatre. There are good theatres in lots of cities. What helps make this festival attractive is the town itself. You can walk everywhere and don’t need a car. Tourists come here because they enjoy the lifestyle and character.”

In the end, the naysayers – including one anonymous writer who sent him a death threat during the campaign – proved right: Stratford wouldn’t elect Rickett to town council. The 2366 votes he received this past November were an improvement over the 1856 he polled three years ago, but still not enough to get him a seat. The sigh of collective relief from council chambers and the political establishment was audible, but some were disappointed.

“He would have made a good councillor,” Giannakopoulos states. “He would make a better planner in this community than the planners we have now, by far. Communities lack vision and it always comes back to haunt them. A lot of communities like London, Brantford and Kitchener, they took stores off the main arteries into downtown and threw up malls. They’re now having huge problems trying to revitalize themselves and Chris understands that.”

As for Rickett, he smiles resignedly and says he feels like he’s in “mother-mode. You can tell the child what to do, but the child makes its own mistakes. I won’t take any pleasure ten years down the road saying, ‘I told you so’.” He says the two election losses have only confirmed what former Lt.-Gov. Alexander told him, but he remains stubborn about the way he wants to run his politics.

“If I ever do get elected,” he says, “I want to do it on my own terms. I want to prove them wrong, I don’t want to hide behind an image. If I’m going to involve myself in a democratic process, I’m going to offer you a choice. You can like me, you can hate me, you can think I’m a drunk or a drug addict, you don’t like my ideas, whatever, then don’t vote for me. If I were elected, I wouldn’t change a thing. I’m a package deal. I smoke dope, I drink beer and every once in awhile I go out and get crazy. Everybody has drinks once in a while and tells raunchy jokes; it’s not that big of a deal.”

“You have to understand,” he extrapolates, “I’m not a politician. I don’t want to be a politician, period. I’m a politician by default. There are so many important issues in this town, and since nobody’s getting up and talking about them, I feel obliged to step forward. If somebody else did, I’d be happy to write about them, that would serve me much better. Naturally, there’s part of me that wants to be a councillor and sit at the table where decisions are made. But my first priority is concentrating on my writing – whether political writing or fiction – and not running for office.”

Rickett moves into his fourth year of publishing with too many things on his plate to waste time navel-gazing about past-and-future elections. There’s that nasty business of Murphy’s lawsuit, with Rickett still awaiting a decision by Judge McDonald. There’s another letter to compose for the Beacon-Herald. There’s the next issue of Ham, the appropriately titled fiction-only sister publication that features Rickett and his friends’ literary explorations.

And of course, there’s always the next issue of Chuck. It’s time-consuming and sometimes stressful – “I think about quitting every day,” he sighs. He’s lucky when he breaks even on his printing bill, and the days between issues seem to get shorter and shorter. But just when he thinks he’s had enough, he’ll receive a new tip and a story falls into his lap. Yesterday he was writing about the wisdom and necessity of a new armoured vehicle that the police force received from a private donor. Today he’s digging up details about some suspicious deaths in the Stratford jail back in the 1970s.

“If I gave up on Chuck,” he says, “I feel like I’d be giving up on Stratford. I’m not ready to do that. I’ve seen too many of my friends leaving town and sitting in trees in BC, but I want to stay and fight for the trees in Stratford. This is the environment that I know and love and has made me who I am. So Chuck plugs on.”

Dave Fisher is publisher of the zine Filler. He lives in Waterloo.

What’s Up, Chuck?

(Free with postage)

78 Wellington Street

Stratford, Ontario

N5A 2L2

www.whatsupchuck.on.ca