In 1979, the Reagan revolution was on the horizon, New York City was on the edge of bankruptcy, and Manhattan’s Lower East Side had been left for dead. In this potent atmosphere, a generation of artists set up shop in Lower Manhattan, spawning a brief but glorious flowering of tough, confrontational work. The music, visual art and films of the “No Wave” scene are defined by their lack of technical polish, and no single work had more disdain for the idea of technical polish than They Eat Scum (1979). This 8mm epic was the debut feature of Nick Zedd, who died on Feb. 27 of this year at 63 — one of the most important and least accessible figures of his milieu.

Imagine early John Waters with no sense of careerism whatsoever and you’ll have a sense of They Eat Scum. The story loosely follows a punk band that moonlights as a gang of cannibal murderers, waging war against society. Late in the film, they cause a nuclear holocaust, and in the end are overthrown by the radioactive monsters they’ve spawned. One character says of the band, “It seems to me that their philosophy can best be summed up in one word: destroy.” The same could be said of the film, which concludes its parade of taboos and grotesqueries with a memorable closing caption: “The End Fuk you.”

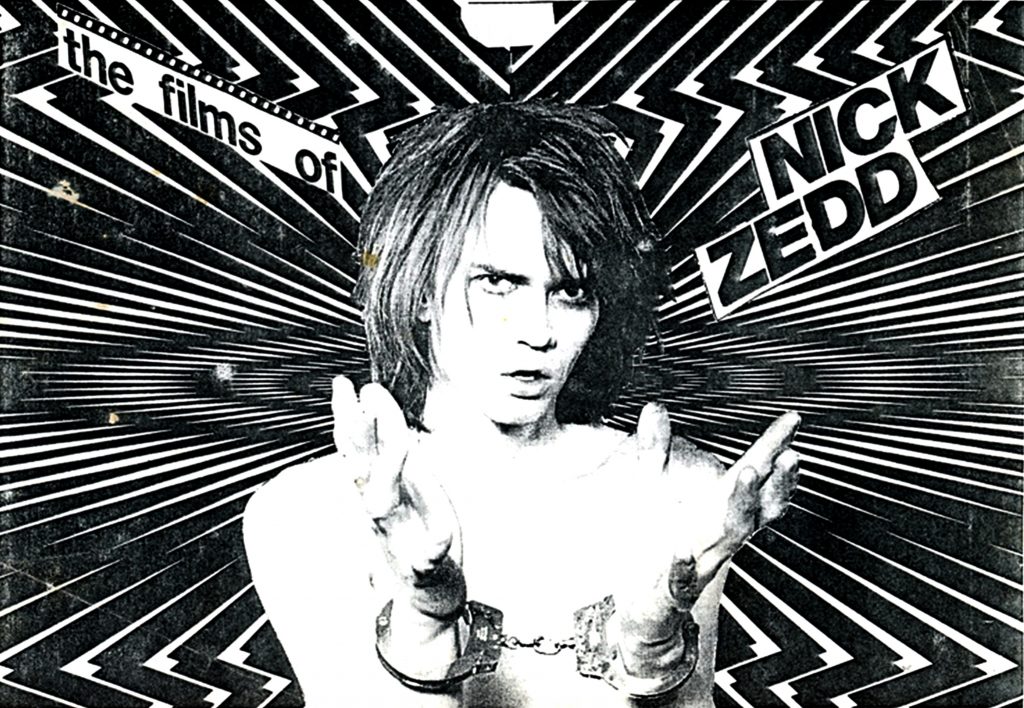

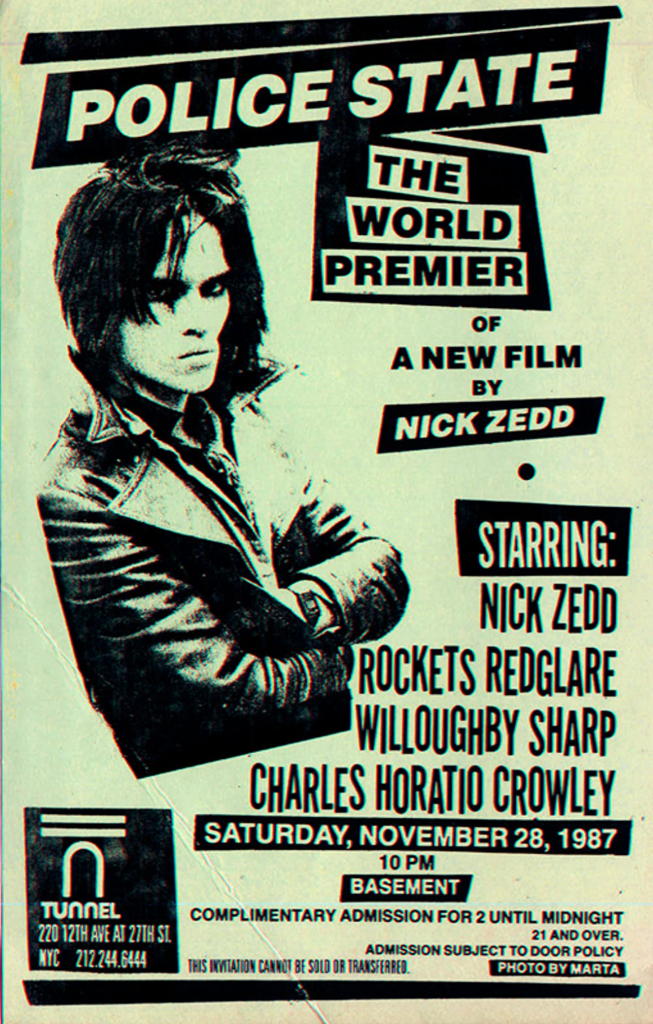

They Eat Scum all but begged to be hated, and it was. Feeling himself misunderstood by establishment alt-culture like The Village Voice, Zedd published nine issues of his own zine, The Underground Film Bulletin. This essential document of its era was a hype machine for such underground filmmakers as Richard Kern, Beth B, Cassandra Stark, and David Wojnarowicz, as well as a venue for Zedd’s spiky, often-hilarious writings. In the fourth issue in 1985, he published his legendary “Cinema of Transgression Manifesto,” which stated, among other things: “We propose that all film schools be blown up and all boring films never be made again. We propose that a sense of humour is an essential element discarded by the doddering academics and further, that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. All values must be challenged. Nothing is sacred.” This spirit is evident in such Zedd films as Geek Maggot Bingo (1983), a spoof of B-horror movies so ramshackle it almost falls apart before your eyes, and Police State (1987), a sandpaper-coarse “fuck the police” parable. But he was also capable of hitting other notes, like in his wistful breakup film The Wild World of Lydia Lunch (1983), or in War is Menstrual Envy (1992), a surreal dreamscape with a luminescent sense of colour.

They Eat Scum all but begged to be hated, and it was. Feeling himself misunderstood by establishment alt-culture like The Village Voice, Zedd published nine issues of his own zine, The Underground Film Bulletin. This essential document of its era was a hype machine for such underground filmmakers as Richard Kern, Beth B, Cassandra Stark, and David Wojnarowicz, as well as a venue for Zedd’s spiky, often-hilarious writings. In the fourth issue in 1985, he published his legendary “Cinema of Transgression Manifesto,” which stated, among other things: “We propose that all film schools be blown up and all boring films never be made again. We propose that a sense of humour is an essential element discarded by the doddering academics and further, that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. All values must be challenged. Nothing is sacred.” This spirit is evident in such Zedd films as Geek Maggot Bingo (1983), a spoof of B-horror movies so ramshackle it almost falls apart before your eyes, and Police State (1987), a sandpaper-coarse “fuck the police” parable. But he was also capable of hitting other notes, like in his wistful breakup film The Wild World of Lydia Lunch (1983), or in War is Menstrual Envy (1992), a surreal dreamscape with a luminescent sense of colour.

Richard Kern became a well-paid photographer and John Waters became America’s funny uncle, but Nick Zedd stayed underground. In the 90s and 2000s he generated bizarre, original programming for New York public access. When the city finally gentrified itself into unrecognizability, he moved to Mexico, where he continued to make art without compromise. I’m grateful to have discovered Nick Zedd’s films in my early twenties because they taught me the important lesson that compelling art is unbound by any rules of aesthetics or taste.

Will Sloan is a Toronto-based writer. He has two – count ’em – two podcasts, The Important Cinema Club and Michael & Us. You can follow him @WillSloanEsq.