Shack finds shells in the dirt sometimes. Marnie said it’s because the ocean was here once, and the dirt used to be the bottom of the sea. Shack believed this, for a while.

Shack lies on the grass, bush twigs waving, her fingers outlined in red where the sun lights up her blood as she shades her eyes. She has to squint, even through her fingers. Shack imagines the ocean here.

Shack squeezes her eyes shut until she sees little coloured lights floating inside them. The damp ground is cold against her back; her front is hot from the sun. She thinks about the ocean being here where she is lying right now. The enormous water, cold and heavy like a slab of iron bigger than a truck, bigger than a train that’s so big she can’t reach the first step. Cold and heavy, and alive with swimming things. Fish that slip past faster than she can notice them — she is only aware of their tails switching into the cold gloom. This saves her from having to imagine them in detail; Shack doesn’t know much about fish. She knows what sharks look like. There are sharks in here too, but she is afraid of them so she imagines them far away. So far away they can’t even eat the fish she can’t really imagine.

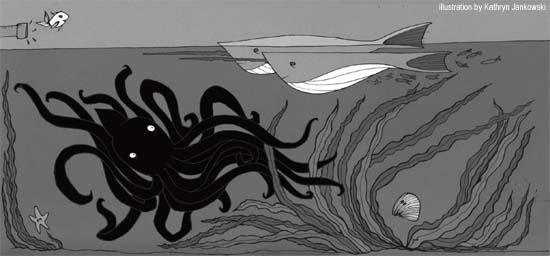

In Shack’s ancient ocean there are other monsters too, and some of them must eat these fish. The big fish eat the little fish, the little fish eat the tiny fish. But the biggest fish are eaten by giant squids, their huge malevolent eyes peering out of their great tall carapaces shaped like church windows. Shack isn’t sure if squids really have big eyes on their heads but she seems to remember that, so she imagines them into her ocean. They wave their big tentacles around with disgusting languor. Shack shivers a little and squirms herself closer to the ground — that is, to the bottom of the ocean, the rutty surface with its little hills and clumps of hard sharp coral pressing against her back. Sometimes the bottom is like a desert, vast stripey sandflats that look like a sidewinder has passed over them, cloudy water floating peacefully above it into the vague distance. Other times it’s treacherous ground, with snapping fish and strange wavy creatures waiting to suck a small toe into their churning insides.

In Shack’s ancient ocean there are other monsters too, and some of them must eat these fish. The big fish eat the little fish, the little fish eat the tiny fish. But the biggest fish are eaten by giant squids, their huge malevolent eyes peering out of their great tall carapaces shaped like church windows. Shack isn’t sure if squids really have big eyes on their heads but she seems to remember that, so she imagines them into her ocean. They wave their big tentacles around with disgusting languor. Shack shivers a little and squirms herself closer to the ground — that is, to the bottom of the ocean, the rutty surface with its little hills and clumps of hard sharp coral pressing against her back. Sometimes the bottom is like a desert, vast stripey sandflats that look like a sidewinder has passed over them, cloudy water floating peacefully above it into the vague distance. Other times it’s treacherous ground, with snapping fish and strange wavy creatures waiting to suck a small toe into their churning insides.

Shack imagines a couple of companionable clams — her and Marnie. Clacking around the bottom drinking the seawater like soup. If she were a clam she would never eat noodles, her favourite, ever again. She imagines a shining golden noodle slipping out of the slack grizzled mouth of a careless fisherman. It falls over the side of his dinghy and descends like an angel into the depths, catching the last rays of sun and settling right into the open shell of Shack the Clam Girl, to her delight. All kinds of things fall into the ocean. She saw a picture once of stuff they recovered from the Titanic. Dishes, dresses, a fountain pen.

She peeks out of her clammy shell and looks around the sea bottom. She is alone. Marnie must be off somewhere. Half buried in the dense wet sand is a great big china platter. There’s a ham bone too. Shack decides that they are from a shipwreck. Maybe that ham bone is even from the Titanic, carried here in the stomach of a big shark that ate the ham, and then died of stomachache and dropped down dead. Then the dead shark got eaten by a bunch of other sharp-toothed fish, which is why its carcass is gone. This is such an elegant solution that Shack pats herself, figuratively, on the back. She closes her eyes, feeling the sun hot on the lids, and sees the shark’s thin dun bones littering the sea bottom around the platter. With a wrinkle of her nose she invents a current to carry them away, leaving behind the shiny clean white old bone of a pig.

Shack stretches on her stomach under an old fir tree whose branches are high enough off the ground to shelter a bundle of small limbs. She breathes in the loamy pinesmell and presses her squeezed-shut eyes against her folded arms. A great big whale cruises gently through the surface waters above her, singing to its babies. That’s the advantage of being a clam — she and Marnie can be clams together without any clam family to make them do stuff. The whale slips through a huge cloud of…those little whalefood thingies, that the whales can eat with their big stripey mouths…its mouth is open and its dinner just flows in as it sails through the water, its big belly smooth except for little encrusted barnacles stuck on it like funny lumps of concrete. The whale’s babies have disappeared now. Shack doesn’t know where they’ve gone, but she pushes them out of her mind. Who cares, anyway. Clams don’t care.

Shack descends on a warm current through the greeny water speckled with shreds of seaweed and the occasional sparkly fish scale turning through the haze; she falls gently through schools of bright tropical fish, past long sharp barracudas with snappy eyes; she imagines with a short giggle that they have little strings of shit waving out of their tiny fish bums like Marnie’s goldfish used to have. Shack felt sorry when Daddy flushed it down the toilet, its bugging-out eyes rolling in panic as it swirled around the bowl. Daddy said Marnie wouldn’t need it anymore. Shack remembers how Daddy’s hands shook as he turned the fishbowl upside down. Scummy water sloshed out. Mummy wailing in the other room. Shack’s chest feels tight, but then she imagines that the fishy swam all the way through the dark dark sewer and emerged into the wide warm hazy light of the sea, the sun slanting down through the water in diffusing stripes. Shack the Clam Girl, floating down toward her resting place on the sandy bottom, sees the little golden shiny fish swim past in the empty water. It doesn’t see her, but it is swimming with a little spring of happiness in its wiggly tail, free now from its bowl and the long cold sewer. It glides away as Shack falls further down and comes quietly but firmly to rest on the ocean floor. She peeks out of her clam shell again. Shack is sure for a second that she sees Marnie scooting along the horizon, but as she starts forward, Marnie Clam disappears into the distant murk. Shack feels a pang of sad disappointment. But maybe it wasn’t Marnie. And even if it was, she’ll come back, because this spot of sand is where the clam girls live.

Shack rolls onto her back. She breaks dried pine needles into bits with her fingers, keeping her eyes closed. Here under the tree the dog could find her probably, if he wasn’t chained in the yard all the time, but the grownups can’t. They never come out here anyway. They’re always sitting on the porch having beer, or working around the house. They don’t ever come out to the edge of the trees to imagine things. Shack pictures the great currents that roll around in the sea, bigger than roads, bigger than rivers. She is a little clam baby, speeding along in the water, joyfully tumbling as if on the best ride in the world — but even better, because rides always end too soon. In this ocean world, nothing ends until you want it to. Even the fish are willing to be eaten by sharks and squids, and the little whalefood thingies are willing to sail into the whales’ big strainer jaws, because everyone has to die sometimes and if someone makes you die it’s bad but if you decide it yourself it’s okay. Shack the clam baby drinks her seawater soup and grows bigger, into a small-size clam, and as she gets heavier she descends further. It makes her anxious to be weighted like this. Her shell gets thicker. It is her armour, but she also feels trapped by it. She wishes she could still float freely, but as she gets bigger she floats less. She looks around to see if Marnie is getting heavier too, and sees in the distance Marnie Clam Girl, looking fearfully over her shoulder, being hustled away into the gloom by Daddy Clam and Mummy Clam. They don’t mean to hurt Marnie. It will be an accident. They only mean to teach her manners, but they will teach her too hard, and she will become cold and silent. Shack the Clam Girl tries to cry out before Marnie disappears from view, but water fills her mouth and chokes her. Clams can’t talk anyway. Daddy told her concrete is made of ground-up stuff, maybe shells too. And sand. It’s like a solid slab of sea where the sea used to be. In her mind, Shack feels the hard-packed wet sand bottom of the ocean. It is hard like cement. Daddy told her there is a difference between concrete and cement, but she can’t remember what it is. She asked him and he didn’t answer. She wasn’t watching his face so she made the mistake of asking him again and he smacked her, but she saw it coming and he only got the top of her head, not her face. Then she ran. She doesn’t want to think about Marnie Clam any more, so she imagines herself flowing through a patch of beautiful tall undulating seaweed. It is waving slightly in the gentle current, making everything look glowy greenish. Shack loves the feeling of having the seaweed garden to herself, slipping through the waving beauty and feeling the friendly fronds brushing her shell as she passes. She is full of wonder, never knowing what she’ll see as the lovely wavy reeds part so she can pass through. But then she thinks that if she can’t see what’s there, maybe she is not alone. Maybe there is something dangerous, and if she makes a wrong turn it could be angry. She tries to imagine the seaweed ending here, but she still feels the menace at her back.

She hitches a ride on a fast current and feels relieved. Then she hears it. Well, she doesn’t hear it, exactly — she doesn’t even know if clams can hear. But she knows that Marnie is crying out for her. Marnie is afraid. She has done something wrong, and now she has been taken away by the family clams. Shack knows that Marnie is very far away. The ocean is so vast, it’s impossible to know where Marnie could be. The family clams could have taken Marnie anywhere, off the coast of Africa, or to the Arctic. If she is in the Arctic Ocean Marnie will be cold, so Shack hopes it is Africa. Marnie was always cold when Daddy or Mummy locked her out as punishment. She would stumble forward in the morning with her hands stiff and white, trembling. Shack would let Marnie put her hands inside her coat while they waited for the school bus, and she would stroke Marnie’s pale face where it lay on her shoulder. Marnie might be cold even if she is off the coast of Africa; the water is deep.

Shack squeezes her eyes shut and tries to remember the seven oceans. Or is it five oceans. Five oceans, seven continents? Seven seas — it’s seven seas. Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic, Indian, African. Shack’s throat hurts. She can’t remember. If she can’t remember the oceans, how can she find Marnie? Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic. Is the Arctic an ocean? Shack’s stomach hurts. What can she do anyway, she’s just a clam, but Marnie is waiting for her. The darkness of night at the surface makes the sea-bottom black. But Shack the Clam Girl lives here, so she can see a little bit, just shapes. Marnie’s faint crying scrapes her chest. It grates against her shell like metal rubbing metal.

Suddenly Shack knows. She imagines a shark. A huge one, bigger than any one that ever lived before, with enormous crusher teeth. She sends it through the water like a missile; she gives it super smell powers so it can find Marnie. She is drawn along in the stirred-up water behind the shark, like being sucked after a giant floating factory. As the shark swims it eats everything in its path. It is so big and powerful that when it comes upon the whale it eats her, too; she is crunched and disappears. Shack feels regret over the mummy whale, but then she remembers this mummy lost her children. So who cares?

In the powerful wake of the enormous monster shark, with its steel grey sides like a huge submarine, Shack is pulled through the world’s oceans. They cross the dark Atlantic untouched by the storms on its surface; the warm Pacific; the frigid Arctic populated by narwhals, which Shack proudly remembers have those twisty things on their noses, like unicorns. She is grateful when they leave the Arctic Ocean and swim into the Indian Ocean, which smells fragrant and exotic, because it means Marnie will be warmer. Shack can’t hear her crying anymore and feels a low sort of dread. She wills the shark faster. Wherever Marnie is, they will find the family clams, and Shack will make the mighty shark crunch them, especially the Daddy Clam. Because what happened to Marnie is his fault. He was the one who punished Marnie. But it’s the Mummy Clam’s fault too, because she lost her child. Shack’s chest is tight again and she tries to clutch the shark’s tail because she is suddenly afraid she will not be able to keep up with him. But she is a clam and doesn’t have hands. She despairs as she sees the shark pulling ahead, getting farther away.

But the shark isn’t disappearing. He’s circling, black eyes aglitter, his mouth half-open in anticipation. There on the sea floor is the clam family. The Daddy Clam is breathing heavily, leaning on his shovel. The Mummy Clam is collapsed in her shell by his side. Shack doesn’t see Marnie. She knows this is because Marnie is already dead. The shark’s hot saliva is dropping through the seawater, making little drop-shaped indentations in the sand as he circles lower, toward Daddy. Daddy doesn’t seem to notice; his gaze is fixed on the patch of concrete before him. He has mixed and shovelled it smooth at the edge of Mummy’s garden. Shack fills the monster shark with furious energy and has him dive at Daddy with supersonic speed and bite him in half; as Daddy’s blood starts to film through the water the shark chomps him frenziedly. Daddy’s flesh and bones slip from the shark’s manic jaws in shreds and splinters.

When the shark has ripped apart the family, Shack imagines it crunching into the fresh concrete with its big jaws. It rips away the hardening stuff. It uncovers Marnie’s clean little shell. Then Shack the Clam Girl sends the shark away. She briefly regrets it, for she needs help carrying Marnie back home. Then she decides it doesn’t matter where in the world’s oceans she lives, as long as she can stay beside Marnie. Or Marnie’s shell anyway. Empty, it’s all that’s left of her. Shack drops onto the sand next to Marnie’s shell and, feeling a fluttering in her clam heart, squeezes into it. It is comfortable. The water here is warm, and always moving.

Elise Moser’s first novel, Because I Have Loved and Hidden It, appeared in 2009 from Cormorant Books. She lives in Montreal.