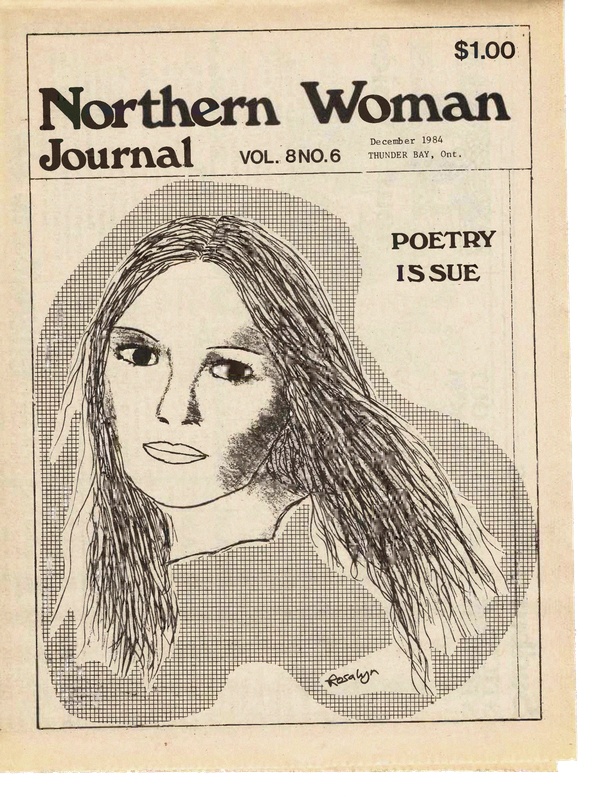

I always thought I’d gotten into zines through comic conventions and my own dorkery, but I’d missed a connection to self-publishing that was closer to home. My mother and many women I knew growing up in Thunder Bay were contributors to a long-running feminist periodical: Northern Woman Journal.

I always thought I’d gotten into zines through comic conventions and my own dorkery, but I’d missed a connection to self-publishing that was closer to home. My mother and many women I knew growing up in Thunder Bay were contributors to a long-running feminist periodical: Northern Woman Journal.

With over 100,000 people and 14,000 kilometres from Toronto, Thunder Bay is the biggest settlement in Northwestern Ontario and often serves as a regional hub. In April 1973, it was the site of the Northern Women’s Conference, attended by 600 women who wanted to organize. The conference led to the formation of Thunder Bay’s Northern Women’s Centre, small interest groups for working women, day care, consciousness raising groups, birth control information and a monthly newsletter.

Northern Woman Journal’s subscription cost a dollar “if you can” and was free for single parents and seniors. The first issue opened on an editorial letter on choosing the Women’s Lib raised fist symbol as their logo: “it was time to review the purpose behind why women are coming together and where we might be going.” They had book reviews, meeting announcements and a legal facts section: “Did you know that? the law does not require a woman to change her name when she marries.”

By 1976, NWJ readership had expanded across the country, even as local subscriptions lagged behind. The collective had been approached by libraries and universities across Canada and America for subscriptions as a record of the ongoing women’s movement.

NWJ received no government funding besides a single salary in 1977, an arrangement they found disruptive to the collective energy.

Headquarters moved from contributors’ homes to the Northern Women’s Centre space at the Thunder Bay YMCA. NWJ and a number of women’s groups then moved into 316 Bay Street, former home of Finnish cooperative restaurant The Hoito.

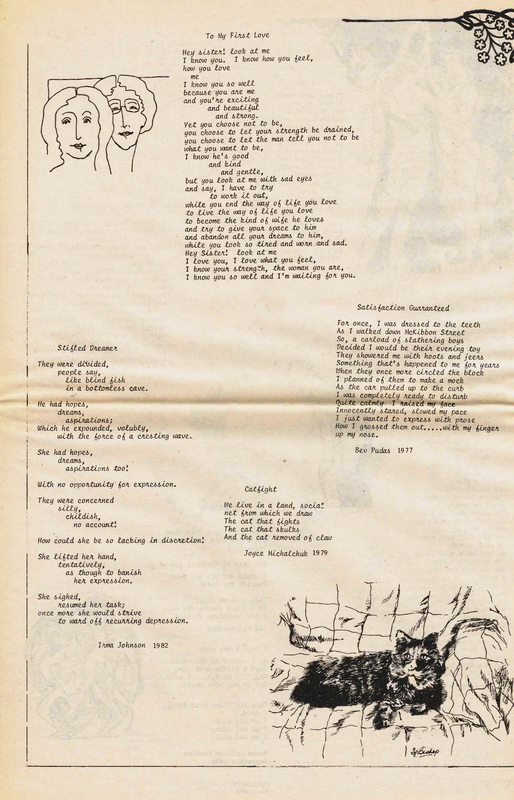

Collective consensus was crucial to NWJ. Each issue started with a group brainstorming session to choose a theme like sexual assault, the arts, prisons, women in the trades. Members would put together book reviews, artwork, poetry and news stories on the local, national and international levels. Contributors reminisced of “the hours spent debating the political correctness of accepting an ad from a hairdresser” and “doing one page about 10 times and nobody getting ANGRY.”

On printing day, one woman would type up copy into columns on an electric typewriter. Volunteers would spread out the issue’s pages, glue and lay out on the restaurant’s original counters and stools — still smelling of the Hoito’s fryer oil.

There were illustrations of how to insert a diaphragm and give a yourself a breast exam, a legal advice column and reprinted material from influential works like Off Our Backs, Upstream and Canadian Abortion Rights Action League. There were calls to action for contacting politicians (“feel free to call and fax Mike Harris your thoughts on his social cuts”) and suggested ‘guerilla tactics’ like defacing sexists ads with stickers reading “This ad insults women.”

There were illustrations of how to insert a diaphragm and give a yourself a breast exam, a legal advice column and reprinted material from influential works like Off Our Backs, Upstream and Canadian Abortion Rights Action League. There were calls to action for contacting politicians (“feel free to call and fax Mike Harris your thoughts on his social cuts”) and suggested ‘guerilla tactics’ like defacing sexists ads with stickers reading “This ad insults women.”

In 1983, NWJ collective members Anna McColl and Margaret Phillips opened the Northern Woman’s Bookstore. The centre, the bookstore and the journal shared space over the next five years until NWJ moved out, citing a deteriorating relationship with the building.

There was a vast field of similar publications across the country at this time. NWJ sent an attendee to the Canadian Feminist Periodicals Conference in 1986 to learn from the women running Broadside (Toronto) and Pandora (Halifax), among others.

By 1990, NWJ’s readership had switched over, with women in rural Northwestern Ontario communities as their most consistent supporters. Subscriptions were up to $6 but finances were always precarious.

By the end of 1995, NWJ was one of the longest-running feminist periodicals in North America, reaching 22 years and 16 volumes; however, the collective members did not have the time and energy to continue production. There was a call for other women to carry on the project. But there were no takers.

I’d never read NWJ growing up but when we were putting together my mom’s memorial service, I knew I wanted to have it represented in some way. It didn’t take me too long to find old issues online — the back catalogue had been digitized in 2013 by the Northern Woman’s Bookstore.

NWJ included my favourite feature of any small newspaper: shout-outs of rage-inducing and praiseworthy news. A thunderbolt to the all-male masthead of Playgirl “a Magazine of Entertainment for Women,” a thunderclap to a local appointee to Status of Women Canada.

It was wild to see my old home phone number printed with exhortations to call my mother, Miriam, to discuss Fat is a Feminist Issue, or to petition for nuclear disarmament. I also found my own chub-by-cheeked face smiling in a baby photo round-up of “Future Feminists.”

In the December, 1990 issue’s section titled ‘Our Favourite Anecdotes, Horror Stories, Adventures/Misadventures,’ one contributor muses, “the radical irreverence with which we looked at life/our lives/men,” and it comes through very clearly. There is so much care and humour evident in these pages. I can feel a MAD Magazine energy in calls for subscribers and contributors like, “Don’t let a three year old die” and the 1979 cover that bears a giant tombstone reading “RIP?”

The centre, now named the Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre, continues to serve women, trans and nonbinary people in Thunder Bay and the region experiencing violence, poverty or issues with legal and administrative systems. They recently started up an online newsletter, Feminist Dispatch, in May 2022 for feminist analyses, program updates, event announcements and resources. It is also open to submissions of art and writing.

The wheels keep turning. As I read repeatedly in NWJ’s pages: “we must work collectively — if we don’t, our energies die.

Shivaun Hoad grew up in Thunder Bay, Ontario, where she learned how to keep bees and identify scat. She now lives in Toronto, shunning all wildlife. Shivaun makes zines about death, robots, professional wrestling and brain injury. You can find her online @shivaunish.