Like a lot of horror hounds, Corinne Halbert was exposed to the genre at a young age — maybe too young. At five, she recalls watching The Blob with her dad and brother and being plagued with nightmares that the gelatinous pink entity would swallow her classroom. “My brother held my eyes open,” she remembers. “I am forever haunted by the Blob, and it’s the stupidest thing ever.”

Many of Halbert’s memories of her family are also shadowed by tragedy. Shortly before her eighth birthday, Halbert’s father committed suicide. She lost her grandmother to a long and protracted illness at 15. In mid-2019, while Halbert was working on a zine called Demonophobiac, her stepfather died, and a fresh wave of grief inexorably bled into its storyline.

“My work comes from a place deep inside of me that’s incredibly real, and that can be scary for some people,” Halbert told me. “But there’ also a sense of humour — if you happen to have one yourself.”

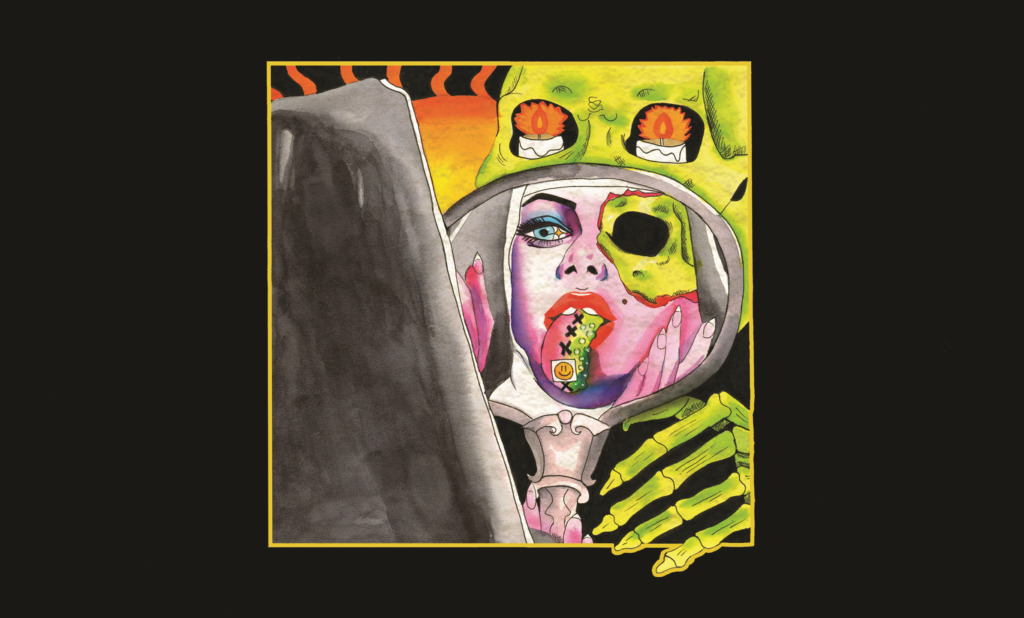

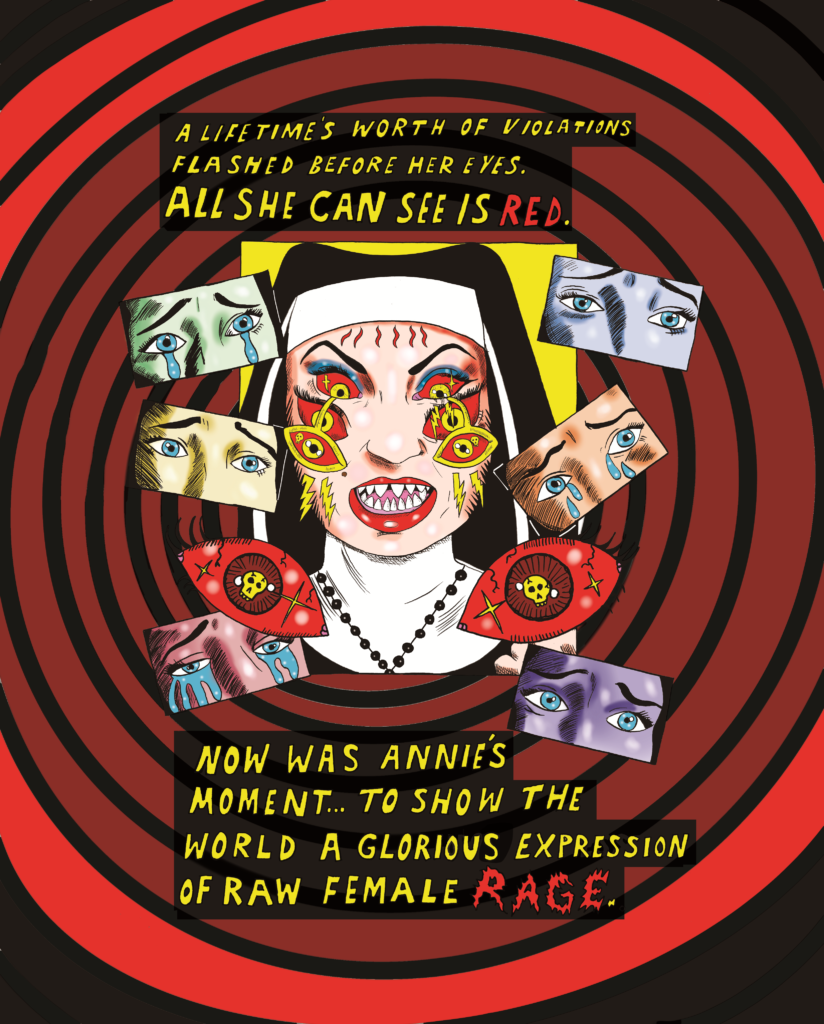

Halbert’s Acid Nun comic feels like the zenith of a boundary-breaking and fearless career. The three-issue zine series, self-published by Halbert over the pandemic, has now been collected and re-released as a full-length graphic novel by Silver Sprocket. It follows the story of a fallen nun, Annie, whose foray into psychedelics takes her on a horny, violent, blasphemous and often relentlessly dark journey. Through the reflective power of drugs, her resilience and the support of best pals Ellie (a demon) and the high priest Baphomet, Annie learns to confront her fears in a quest for healing and self-love.

“One of my only memories of my dad is watching schlocky horror movies — I think that’s a big part of my obsession,” Halbert says. “Maybe I’m just trying to recreate this thing with my dad. That’s kind of a beautiful thing. The horror genre has always helped me deal with the real horrors of life — it’s a cathartic outlet in that way.”

As Halbert continued experimenting with painting and illustration in school, her aesthetic tastes expanded as well. She studied film at the Massachusetts College of Art and got exposed to the likes of Ingmar Bergman and Maya Deren, nunsploitation classics like Ken Russell’s The Devils and oddities like the 1981 shot-on-video slasher Sledgehammer. She developed a fascination with “the highest art meeting the sleaziest sleaze.”

As Halbert continued experimenting with painting and illustration in school, her aesthetic tastes expanded as well. She studied film at the Massachusetts College of Art and got exposed to the likes of Ingmar Bergman and Maya Deren, nunsploitation classics like Ken Russell’s The Devils and oddities like the 1981 shot-on-video slasher Sledgehammer. She developed a fascination with “the highest art meeting the sleaziest sleaze.”

While studying for her MFA, Halbert threw herself into Chicago’s flourishing zine culture, working at the immortal Quimby’s Bookstore and publishing work in cult cinema zines like Printsploitation (created by Halbert’s now-husband, zine-maker and illustrator Scott R. Miller).

She started producing her own zines at a 24-hour Kinkos in Wicker Park, an infamous spot where outsider artists like Wesley Willis printed various ephemera. Among other projects, this period birthed what Halbert calls ‘her demented labour of love,’ the six-issue black and white Hate Baby series.

Porn, sleaze, S & M, arthouse trash, the playful ghoulishness of EC Comics, religious iconography and nightmarish psychedelia; Hate Baby has it all. Halbert wasn’t just doing this for shock value. There’s a genuine exuberance in these twisted drawings and stories — a deep and abiding love for the dark and dreadful, shaped by an increasingly personal touch. By the final issue (Hate Baby 666) Halbert’s fascination with Catholic iconography and naughty nuns had fully emerged, with various sisters of the cloth behaving badly with a bevy of sexy snakes, goat demons and skulls.

“The beautiful thing about self-publishing is the limitless freedom. You can be as weird as you want,” Halbert says. “Those zines are funny for me to think about because they’re so off the rails — I was definitely working some stuff out.”

When the pandemic hit in 2020, Halbert began creating colour-drenched psychedelic paintings to keep herself occupied and focused on the longer-form narrative that would become Acid Nun.

Each page of Acid Nun is saturated with swirling colours as Annie’s visions and memories unfurl. On one page, a fox named Finius leans over Annie, rendered as a saint in a stained-glass window, her heart exploding with flowers. “There’s rich soil beneath all that pain,” Finius consoles. But much of Annie’s journey is heavy, freighted with suicidal thoughts, trauma and self-doubt.

In Acid Nun #3, Annie falls deep into her own consciousness, trying to find solace in memories of watching horror films with her dad and the kindly visage of her grandmother. But those thoughts are soon replaced with visions of death; worms sliding in and out of empty skulls deep in the earth.

In Acid Nun #3, Annie falls deep into her own consciousness, trying to find solace in memories of watching horror films with her dad and the kindly visage of her grandmother. But those thoughts are soon replaced with visions of death; worms sliding in and out of empty skulls deep in the earth.

“I don’t think I really allowed myself to grieve at first,” Halbert says. “I had a lot of stuff festering and it all compounded into this giant grief monster. Doing Acid Nun helped me untangle all this stuff and at the same time it was also terrifying. I filled my mind with every thing that could go wrong, every fear. My brain was feeding me at all times. I had to fight against that while working on this thing. It was complicated. But ultimately it was one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done artistically. I pushed through and got it done.”

Acid Nun isn’t all pain — there are house parties, creepers, brawls, bludgeoning and bacchanalian sex. It’s all part of Annie’s journey of empowerment and more importantly, of learning to love herself as a scarred but mighty survivor with macabre, decadent tastes.

“I put every bit of my heart and soul into this — and I think it does show,” Halbert says. “ I hope it helps other people who feel grief, or trauma, or just feel like a fucking weirdo. I hope it lets them know they’re not alone. Because it really does help to know that.