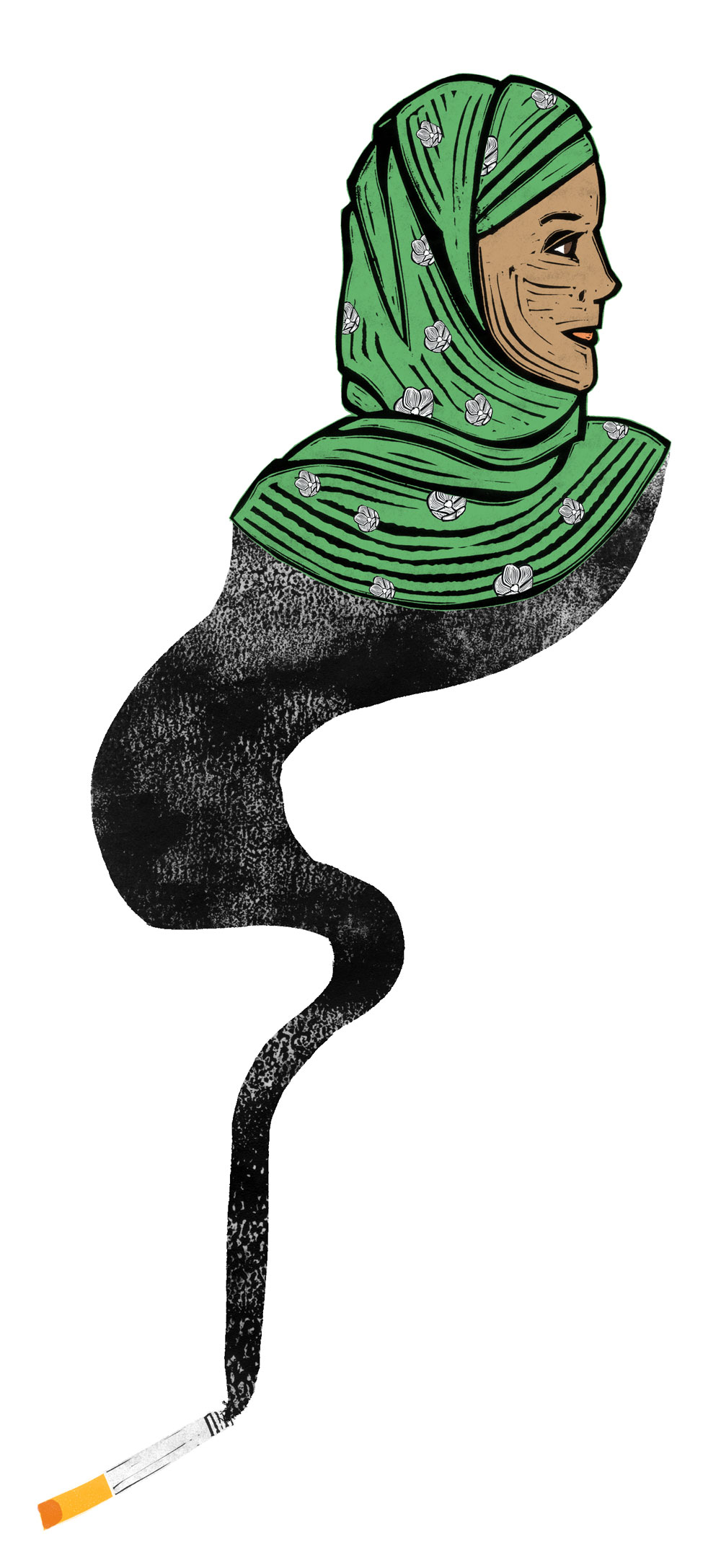

THIS WAS BACK when I used to smoke, because everybody used to smoke, everybody used to walk around with their pockets full of cigarettes. There’d be little glass rooms in the corner of each office, and that’s where you were supposed to light up when it was too cold to go outside. So I was sitting in there all on my own when she walked in, and those rooms were small, no bigger than an elevator. You had no choice but to talk. I said hey and she said hey back, and she was wearing these old-fashioned slacks, I’ll never forget, these old-fashioned slacks and her headscarf. She sat across from me and pulled out her lighter.

I said I hadn’t seen her around, and that was because she was new, she said, she was the new secretary. She had on this deep red lipstick, almost purple, that stained the end of her cigarette. She had an accent, too.

Where are you from? I asked, and her back went bulletin board straight. She looked at me, and there’s another thing I’ll never forget, the way she searched, hesitant, expecting to find something cruel. There was a knot in my chest for just making her wonder. I was someone who gave off that possibility, I realized.

Pakistan, she finally said.

“Oh.”

Her headscarf was green with these little white flowers, and it made me think of my garden, so I told her that. I felt stupid afterwards. She gave me this look like she didn’t know what to do with me.

She must have known then, I think, that I wasn’t quite like other people, that I wasn’t able to carry on conversations the way that everybody else did. She smiled, still a little cautious, but then she said that her and her daughter liked to garden. They were going to plant rhododendrons in the spring, and if things were more settled maybe she’d stop smoking by then, she wasn’t sure. She’d picked up the habit just after she’d arrived here, after her sister had moved in to help with the children. Anything, she said then, tapping her fingers against the cigarette, to help with the stress.

We started smoking together every day after that. We’d wait till the rest of the office finished their post-lunch cigarette, all crammed into the glass smoking room like it was a bucket of dead fish, then we’d go in after it had emptied. The air was almost grey by then, and I could feel it on my skin.

Smoke-dust, she called it. Said it clung to fabric.

I asked her what it was like, to live in Pakistan, and she said there were mountains and they used to carry things on the backs of donkeys. She said there used to be satchels full of almonds, and that their insides were rich as butter. There used to be pomegranates sweeter than sugar. When her husband was alive, she used to ride on the back of his motorcycle, and they’d swerve between cars and rickshaws to get to the market to buy vegetables and sometimes orange pop for the kids. Her face changed when she talked about Pakistan, I noticed it right away. She’d look past me, past the walls of the office, and stare right at a bag of potatoes or butternuts.

Those memories were from years ago, I soon discovered. She was telling me about the Pakistan she’d known when she was growing up and then when her children were very small. She didn’t want to talk about the more recent years.

One day, when my car was in the shop, I saw her on the bus on the way home from work. She sat down next to me and we talked a bit, though only about the snow, and the kind of boots you needed to keep your feet warm. We were used to sitting opposite one another, so it was strange to be next to her, to have our arms in puffy jacket sleeves pushed up against each other. She didn’t look at me for a while, and then she did, turned her head to the side and glanced up from beneath her scarf.

What are you doing for dinner? she asked.

I have dinner in the freezer, I said. A frozen lasagna and garlic bread that I can put straight in the microwave.

She kept her head down, but spoke clearly. She said I should eat with them. That her sister was cooking.

We stepped off the bus together. I followed her down the sidewalk and noticed how her boots were worn at the heels, how she folded her arms in front of her body to try and keep in the warmth. We got to a long row of townhouses and turned down one small street, then another. Her place had three concrete steps leading up to a little doorway with a fake cedar wreath. She unlocked it and there was warm air coming at us, and light, the TV making noises from somewhere inside. The smell of spices almost made me sneeze. Then there were the kids, three altogether, who were running up and launching themselves into her arms as if she were lake water.

They didn’t know what to think of me at first. They led me into the kitchen, where their aunt was serving food. She looked up from the stove, and for a moment stared at me as if I had walked in wearing only my underwear. I stuck out my hand to try and shake hers, say nice to meet you, or thank you, but all she did was hand me a plate.

One of the kids pulled out a chair, and then we were all gathered around the small wooden table and I thought about how I didn’t eat properly, not like this, not with other people around. I was the only one who got a fork, because they said they were going to eat with their hands, but I told them that sounded better. The kids tried to show me how to scoop with my fingers, and then they were laughing, because I couldn’t quite do it, kept dribbling food down my chin.

The vegetable was hot and delicious and the bread was soft. She kept glancing at me over the food, sometimes smiling, then looking away. Her sister stared down at the table. I ate too fast and then it was too spicy, and I finished my glass of water, so one of the kids got up and brought me a glass of milk. It will help, she said, it coats the tongue, takes away the spices. I hadn’t had a glass of milk since I was twelve. I drank it down and thought of chocolate chip cookies, told the kids I was going to send them a treat tomorrow.

The next day I went to the grocery store before work, and in the smoking room after lunch I gave her a package of cookies. The wrapper crinkled when I handed it to her. I asked her about the kids, about her two daughters and her son, and she said they were doing okay. It was hard without their father. She inhaled deeply when she told me those things, held the smoke in her mouth for a long time.

Then she glanced up at me again, and the air in the small room was hazy. I got caught in her eyes for a moment.

She looked at me, then glanced down, then looked back up at me again. I wanted to know what the fabric of her scarf felt like, if her hair beneath it was soft.

I went over every Friday after that. I’d leave my car in the parking lot at work and get on the bus with her, and we would talk, slowly at first, but then we’d get more comfortable. In her house we’d sit in the living room on opposite ends of the sofa while the kids ran around, or else we went into the kitchen and she showed me how to marinate lamb in yogurt and spices. The kids starting calling me Uncle, and each week I’d bring them lollipops or caramels or licorice from the corner store.

Her sister skittered around me at first, avoided me as if I was sick, but then one evening she laughed at me while I played with the kids. I could tell that she was startled by it, that she hadn’t meant to. She still wouldn’t look at me. But after that she stopped leaving the room when I came into one. Her sister noticed, and immediately I could see her shoulders relax, the lines between her eyebrows soften. It made my chest feel warm.

Once the kids asked me why I never brought my wife around. I asked them who would ever have me, with my sticking out ears and my tubby tummy. I shook my belly and made them giggle. Then their mother came out of the kitchen, said I shouldn’t be so hard on myself. That I had a gentle soul. She touched the side of my arm and I couldn’t stop staring at her after that. I excused myself to go to the bathroom and washed my face with water so cold it gave me goosebumps.

When the snow started to melt, people went back outside to smoke on the sidewalk. The two of us didn’t change though and stayed in the smoking room. The office was quieter now that it was nicer outside, and sometimes it felt like there was nobody else left, just her and I, sitting an arms’ length away from each other with the dusty smoke air settling into our clothes and skin.

It was around that time, when spring was just starting, that the new guy joined us. He’d just started at the office, hadn’t learned the routines, the way people left us alone because we were each other’s only friends. He hadn’t known that. So he’d walked in and sat down next to me, pulled out a cigarette, asked me for a light. His hair was slicked back with too much gel. It made his forehead look big.

She always got real quiet when she was around new people. She’d just close up, and that’s what happened, she just watched the floor tiles, took small inhales and then exhales.

So the guy turned to me. He just started talking and telling me about the weather. I wanted to tell him to go to hell, but instead I sat there and listened. I sat there and listened and smoked and nodded.

It was all fine, different, but fine, until he turned towards her and stared at her headscarf, at her eyelids because she was looking down at the floor, and said, there’s more and more of them every day.

He laughed then, turned towards me and laughed this horrible laugh. She looked up. It made him laugh even harder, slap his knee.

Doesn’t it get filled with smoke, he said, pointing with his cigarette at her scarf.

Yes, she said after a moment. Her voice didn’t waver.

He laughed again. You people even allowed to smoke?

She looked away and focused on her cigarette. It was down to the very end, the tip almost burning her fingers, and I wanted to reach over and stub it out for her, but I just sat still. She sat still, too. The guy leaned forward, elbows against his thighs, trying to stare past the cloth of her scarf that was draped along her neck. She turned the other way.

You know what I’ve heard, he said, sitting back up, catching my eye. I tried to look somewhere else. I’ve heard that when they’re covered like that, they make up for it by wearing special stuff underneath. He snickered. He blew a puff of smoke out his mouth. You know. Fancy panties and stuff.

She was turned away from both of us now, only the edge of her mouth, the profile of her nose visible, and the orange end of the cigarette was right up against her fingernail. My own cheeks were hot. Do something, I thought. She was making it too easy. Every day she sat in this glass cubicle where people could see her, where people could see that she was different. She didn’t realize that maybe she should be more careful.

The guy looked at me and grinned, and he wanted me to grin back, but what I really wanted was to slam his face into the wall a few times, watch as his teeth fell out.

I wish I had. Maybe I would have felt better, stronger, but I just sat there and let him finish his cigarette, watched as he put it out in the crystal ashtray. He got up and went back to his desk, and then it was just the two of us again.

He’s an idiot, she finally said, and I felt awful for not saying it first.

She got up, and I said I meant to follow her, but I ended up just sitting there. The smoke soaked itself into my cotton shirt, my trousers, and I thought about how it was best to be soft and strong, but maybe I was just soft and weak, a bit blubbery, strangely easy to push over. I imagined myself rocking on my feet and then falling on my back, unable to get up again.

That evening I went to her house and brought extra desserts. There were jelly beans, toffee squares and a bag of colourful marshmallows that were supposed to taste like fruit. The kids hugged me, they climbed on me and ate too much sugar. They ran around the living room, danced to the pop songs on the radio, and I was almost happy again.

She sat next to me on the other side of the sofa. We’d made a bit of small talk earlier and had eaten crackers from a serving plate, but now, she wouldn’t look at me. There was nothing more to say about the weather or about the dinner, so I stayed quiet. She stared ahead at the indents on the coffee table. I wanted to reach out and pull back her scarf, just so that I could see her eyes.

In the other room, her sister was frying something and the oil was popping. One of the kids threw a jelly bean from the doorway, and she got up to scold him, and he started to cry. The living room suddenly seemed very small. The carpet and the walls and the table were all brown, and they were closing in around me, and the music from the radio was too loud. I wanted to get up, to stand and walk a bit and move, but my legs were sinking into the sofa. ∞

_____________________________________________________________________________

Menaka Raman-Wilms enjoys writing fiction, and is a graduate of the University of Toronto’s MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing program. Her short stories have received awards from Room Magazine and the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto Foundation. She also sings, and reviews Canadian fiction and non-fiction for the Ottawa Review of Books. Menaka is currently studying journalism at Carleton University, as well as working on a novel.

Menaka Raman-Wilms enjoys writing fiction, and is a graduate of the University of Toronto’s MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing program. Her short stories have received awards from Room Magazine and the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto Foundation. She also sings, and reviews Canadian fiction and non-fiction for the Ottawa Review of Books. Menaka is currently studying journalism at Carleton University, as well as working on a novel.