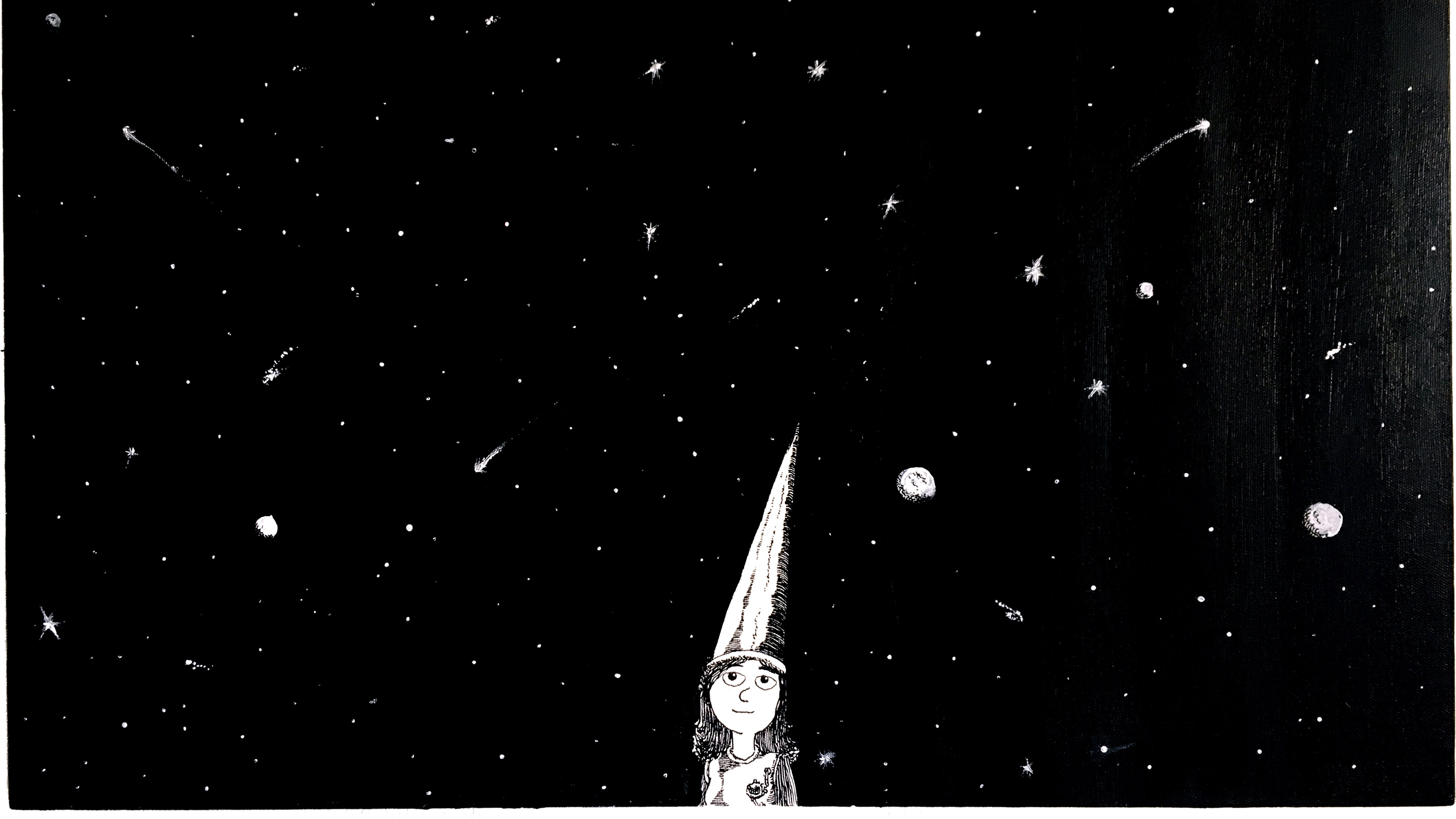

by Georgy Elaev

by Georgy Elaev

Making comics in Siberia can be brutal. In Russia, you can get into big trouble for pursuing free speech, especially with this particular medium.

It happened to my community this year. A bunch of us organize Comic Arts Tyumen, a comics festival. For its second edition, we publicly invited LGBTQ+ artists to participate, as well as feminist illustrator Nika Vodvud and the feminist rock band Pozory.

This pissed a lot of people off.

An anti-feminist shit storm hit our social media. Our host university forced us to remove the post inviting LGBTQ+ people, and one of the organizers was even questioned by the Federal Security Service (FSB).

After all this, there wasn’t much more trouble — but it was intense. The experience reminded our community that our society still views comics merely as entertainment. For organizers and artists, this reality can lead to disaster. But it can also be the motivation we need to try and make things better.

The history of comics in Russia is complex. In the Soviet era, they were considered a dangerous Western influence, but as the USSR began to crumble in the ’80s and ’90s, there was a boom of commercial kids’ comics like Goliath, Tom and Jerry, Bamsee, even Calvin and Hobbes. Kids of this era became the first generation of Russian comic fans — and creators. New Russian comic fans began to produce sci-fi and fantasy stories inspired by their favourite series and strips.

New comic shops and exhibitions like ComicCon emerged in the 2000s, finally opening spaces dedicated to creators and fans. But many of these institutions, were largely focused on mainstream comics, also became gatekeepers. It was hard to engage with them if, for example, you lived way out in Siberia and drew weird stuff that was nothing like Spider-Man.

Back to Siberia. A community of comic artists started to form in Tyumen city around 2014. Some of us opened a pop-up comic book store called Space Cow in a local coffee shop. Soon, local illustrator Vitaly Lazarenko was hosting our regular drink & draw events there.

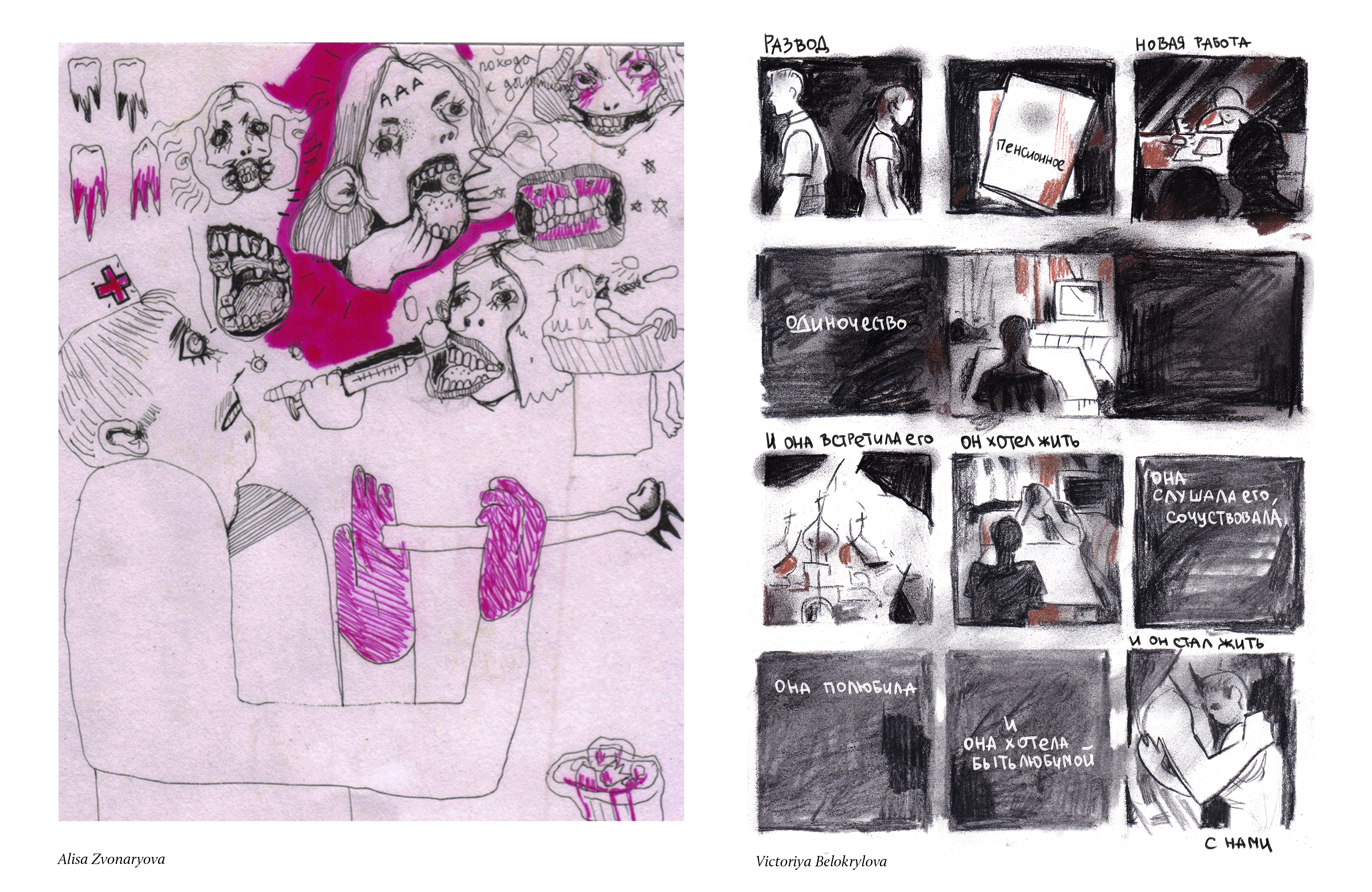

Everything grew from that point. In 2015, Space Cow published its first anthology, Black Milk. This attracted even more readers and artists, and we realized that Siberia had a vibrant community of artists capable of making way more than just short anthology pieces. So, in 2017, we started to print Siberian artists’ solo books as well.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, Tyumen is the resting place of Mikhail Znamensky, who published the first known Russian comic in 1875. When Space Cow took off, the surge in talented young artists made it clear that Tyumen still had some of Znamnesky’s trailblazing comics energy left over.

After touring Siberian comics to other shows in Russia, I realized there was no other community that was organized like our own. So, we founded our own festival: Comic Arts Tyumen, its name inspired by Comic Arts Brooklyn (CAB). I used to just look at pictures from CAB and dream about having something like that here, and lo and behold, we made it happen. The first Comic Arts Tyumen was held in the Spring of 2018, in a three-level skatepark, no less.

Some major figures from the Russian indie comics scene joined us that year, as did David Schilter, from Latvia’s renowned kuš! Comics. We highlighted local LGBTQ+ artists, hosted workshops and talks and, of course, had a big public comics fair. People travelled on trains for days to attend the event, because it was the first truly inclusive indie comics show in Russia, and it wasn’t based in far-off Moscow.

***

Suddenly, there was a huge interest in making comics. Even though funding for comics projects is nearly non-existent here, we kept building, and founded our summer comics school, Comic Camp. Students were producing full books in no time! When I got accepted to CAB in 2018, we quickly translated our books into English, and printed a new anthology to help raise funds for the travel. In the meantime, news somehow spread about the Siberian comics headed to New York — we even made it into Metro, a free newspaper circulated in the subway system.

Suddenly, there was a huge interest in making comics. Even though funding for comics projects is nearly non-existent here, we kept building, and founded our summer comics school, Comic Camp. Students were producing full books in no time! When I got accepted to CAB in 2018, we quickly translated our books into English, and printed a new anthology to help raise funds for the travel. In the meantime, news somehow spread about the Siberian comics headed to New York — we even made it into Metro, a free newspaper circulated in the subway system.

As expected, the festival was awesome, and being in NYC for the first time (stoned and drunk, of course) was mind-blowing. I met all my heroes — Eric Kostiuk Williams, Ginette Lapalme, Fifi Martinez, Tommi Parrish, Lale Westvind, Olivier Schrauwen, Patrick Kyle, Charles Burns, and so many others. Everyone was really friendly and welcoming — a kind of support towards newcomers that you don’t see at Russian comics events. The experience validated all the hard work, and I felt that I’m doing the right thing with Comic Arts Tyumen. I even invited some of the artists I met to come to Tyumen for our show.

Word spread further about our projects and opened up new opportunities. Soon, we got to tour Siberian comics in Germany, and received support from the US Embassy in Latvia towards printing a bunch of new work and bringing international guests for this year’s show.

Then, at the peak of all of this good momentum, it hit — the sudden wave of state scrutiny, anti-feminist abuse, and homophobic vitriol. Yes, it was stressful. But it also gave us the energy to react, to seek more opportunities to change the public’s perception of comics, and to raise awareness about the social problems we see.

In addition to the cultural challenges and a lack of funding, there is also a unique, critical obstacle we face: distance. Distance between Russian cities, and also between Tyumen and “the outside world.” The massive space between these makes travel expensive, slows down communications, and causes artists to feel isolated.

But I believe the distance also gives us something special: the power to see things differently. That’s precisely why we are motivated more than ever, aiming to break through our isolation and share our vision with new friends around the world.

Last year, Broken Pencil published a big spread of surveys of zine cultures from every hemisphere. But the world keeps turning, and the project continues in a new dedicated magazine section for Global Zine Reports. This report is written by Russian indie comics hero Georgy Elaev. Please contact [email protected] if you’d like to tell us all about your local zine scene!