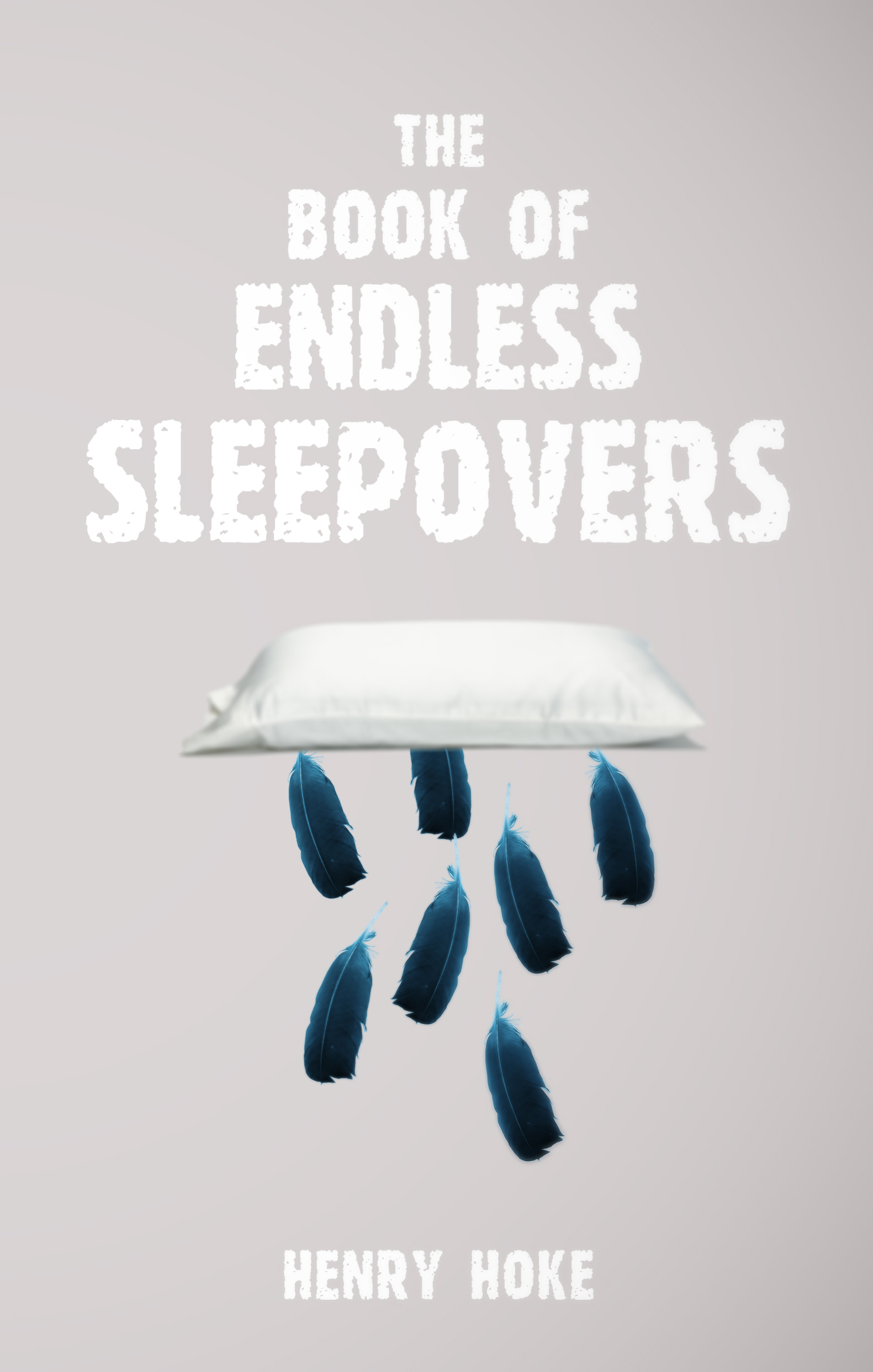

The Book of Endless Sleepovers, Henry Hoke, Civil Coping Mechanisms, 150 pgs, copingmechanisms.net, $15.95

Do you remember what it was like to be, say, nine years old? Or nine and three quarters? Sure, you do. But do you?

Henry Hoke’s ethereal debut pitches a blanket fort on the border between memory and the personal histories we wish for. Stories (or chapters) are composed of vignettes, prose poems, telegraphic description snacks. Each page gently populates a landscape ruled by kid logic, serial gentle awakenings and short-sighted affect.

In the section titled “The Death of Every Pet” the narrator indeed describes the deaths of pets both existent and non-existent without too much differentiation. In “Narration for an Endangered Species” a child-like fascination with the so-called Banshee Whale makes for a mythological poetry: “It’s been theorized that the Banshee can only cry when out of earshot. If the Banshee whale wails and there’s no one around to record it…. In this case, what could extinction possibly mean?”

Some sections introduce names only to leave them behind as their momentary importance fades. Other characters hover and come back with increasing intimacy. Although brothers and pets are especially cherished throughout the book, the opening and closing sections of the book deal with Tom and Huck and their lilting, somewhat ambiguous pubescent romance and best friend adventures. Indeed, the book begins with a graffito, the theoretical phrase: “What If Tom and Huck Fucked?”

There’s something really sweet, and awfully familiar about the Tom and Huck episodes:

“Tom and Huck are on their backs in the grass again.

Huck says he can’t wait to have kids, so he can beat them.

Tom tries to imagine what their children would look like.

How many times can you write the word “pussy” in a book of Mad Libs?

Tonight we’re going to find out. By god.”

The dark honesty of adolescence punctures and deflates the bubbles of nostalgia and timelessness that arise throughout the book. In “Grand Rapids,” something very bad happens to a child. Beloved mothers and pets die. Characters, much like us readers, don’t know how to talk about these things very well.

Henry Hoke does know how. He does it in this book, over and over, through experiment and self-exposure. The writing in The Book of Endless Sleepovers is elusive but trustworthy, exactly as it ought to be. Utterly awesome.