Cell Count is one of the best-known Canadian prison zines that continues to publish today. Produced by PASAN, a community-based prisoner health and harm reduction organization, the quarterly features art and writing by prisoners in Canada and shares health information and resources for prisoners and their families. We spoke to Sena Hussain, Cell Count’s coordinator at PASAN.

Broken Pencil: Tell me about working on Cell Count.

Sena Hussain: When I started, Cell Count hadn’t been published for over a year. So I arrived to a giant pile of requests for subscriptions, a mountain of work that had been submitted, mail, and so many voicemails. Reading through those and the older issues of Cell Count, I realized it’s this amazing archive and documentation of the prison experience since the mid 90s, especially around people living with HIV who are incarcerated. This experience of incarceration through different prime ministers and parties in power, and the influence that had on people’s experiences and the programming, all from people who were actually incarcerated.

So you’re the editor, the publisher — you are the Cell Count nexus in a way. Do I have that right?

Yeah, I manage pretty much all of it. I have a group of online volunteers that help with transcription. That takes the longest. And it’s also kind of intense. I was doing all of the transcription, and then I was super exhausted after because of the content itself.

It gets transcribed and edited. I lay it out, scan and edit, send it to the printer, and pick it up. We get some peers to help us stuff the envelopes for an honorarium. Then I drive all of them out to Canada Post. It can be anywhere between 700 to 1,200 going out.

Whoa, that’s huge. That’s much more than a lot of Canadian small magazines. Am I right in saying that makes Cell Count the largest prison publication in Canada?

That could be. For sure one of the longest running, besides Out of Bounds. I do know that Cell Count is quite popular inside, especially in the federal institutions. It has a harder time getting to the provincial institutions, because provincial governments tend to be restrictive. With federal institutions, people are serving longer sentences, and there’s only one government to hold accountable. Cell Count is also very recognizable. PASAN tables at prison health fairs or pre-release fairs, and people will recognize Cell Count right away. It’s a way to create that connection right away, like, “Oh, I can trust you, you’re the people that put out Cell Count.”

People have a real relationship with the zine, then.

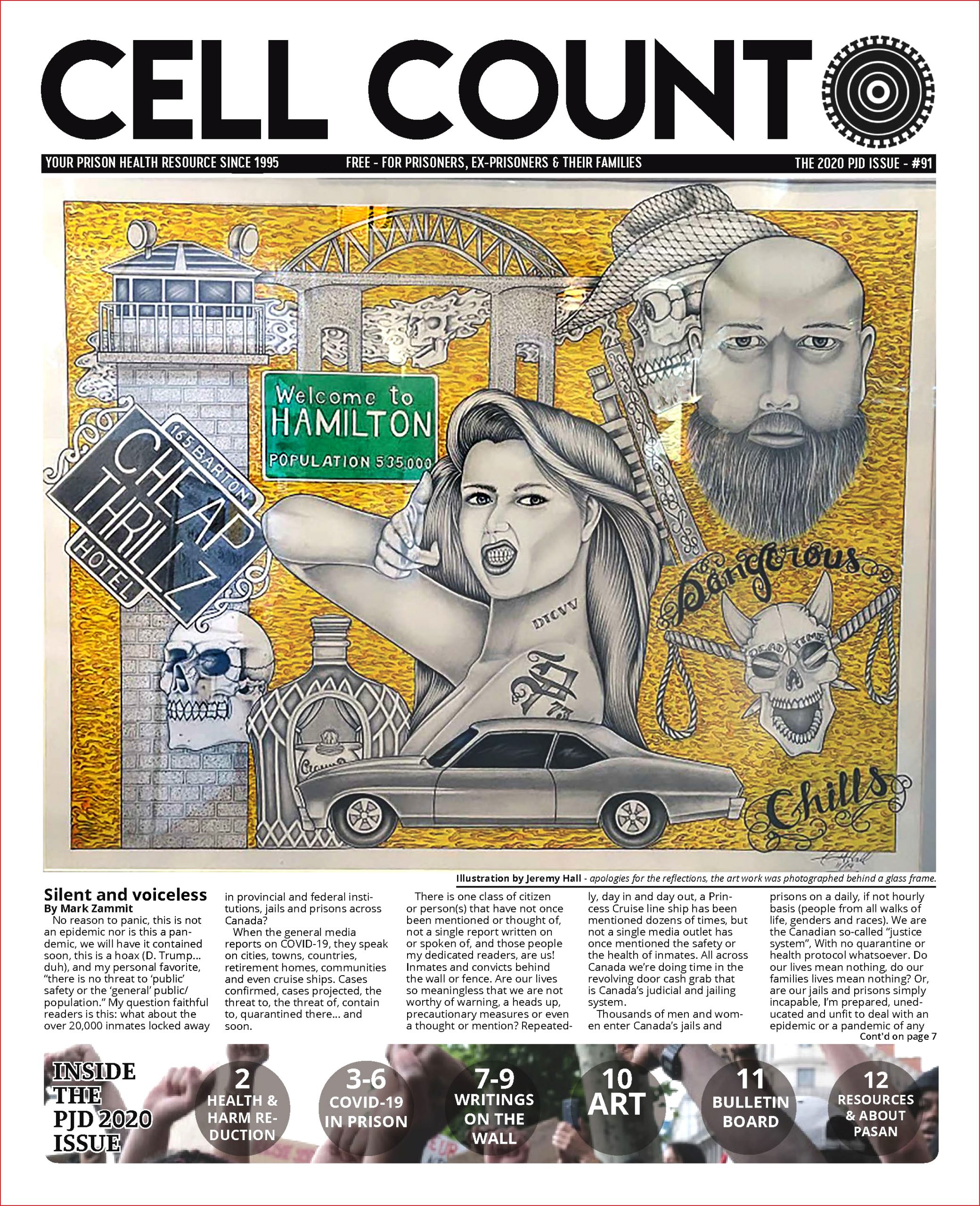

Because we provide people the space to talk about their incarceration experience as freely as we can. People are so enthusiastic about it and want to be involved. The feeling of being published in a newspaper and your peers around you giving you respect and recognition, that’s big. Or being able to send something to your family, you can say, sure, I’m incarcerated, but I’m being published, there’s a sense of pride there. It gives people that sense of being seen, and taking ownership of your own story.

It’s humanizing, yes. And there’s legitimacy to it. That’s part of prison publishing’s long history in Canada, all these rigorous newsletters and magazines.

It’s startling for people to know that, here in Canada, you can be so violated as a human being incarcerated in a country that’s all about being so progressive. It’s such a huge contrast. People inside are just bursting to tell the general public, “This is what’s happening to us.”

I often tell contributors to remember that the audience isn’t only people who are incarcerated, it’s people on the outside too. It’s important for them to know what’s happening inside. The families of people who are incarcerated, they read this stuff too. We’re also funded by both the federal and provincial government as well. So in that way, we’re able to provide Cell Count for free to folks inside.

How does this fit into the broader work of PASAN?

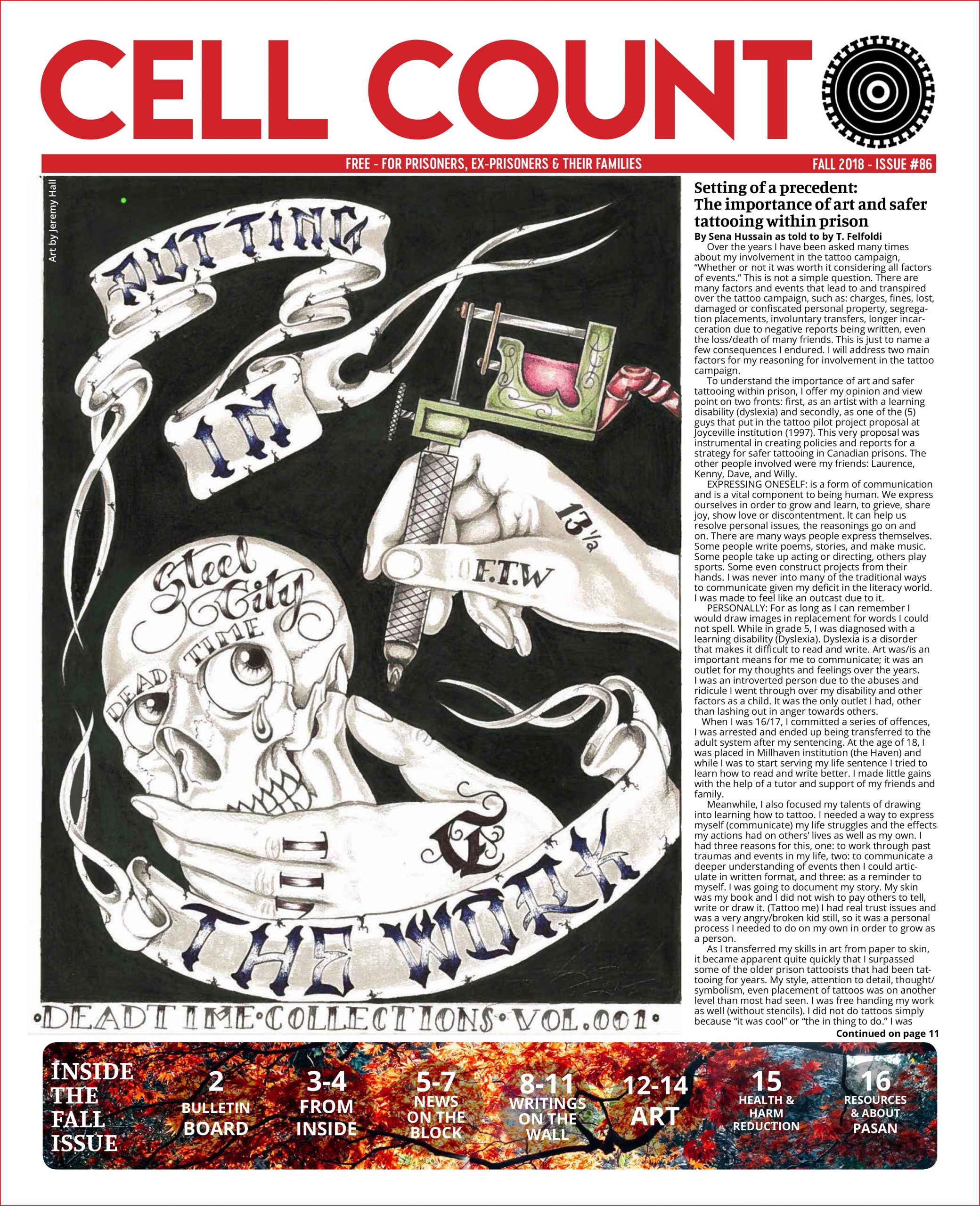

We do health and harm reduction, so we focus on HIV and Hep C because there’s a higher rate in the prison population. That’s because people don’t have equal access to basic health care.. For a long time, there was no needle exchange program; there’s still none in provincial institutions. We’re up against the guard, the correctional officers’ union, who are super against the needle exchange program. Then tattooing is also not allowed inside. So people make their own tattoo guns and have to find a way to clean their equipment, which is impossible. But with tattooing there’s a high risk of Hep C transmission.

We raise awareness about that, and about healthcare, how to advocate for yourself, to document your experiences. And we go in with the intent to build emotional resilience, talking about trauma, mental health, relationships. We’re trying to build people up in a context where they’re being broken down. We don’t allow corrections inside of the room with us when we do our groups or one on ones.That’s amazing that you’ve negotiated that, how is that possible?

We are constantly negotiating that relationship with corrections. We’ve definitely been banned in the past. But we also have people who work for the prisons, who love Cell Count and see it as a very important resource for people inside, which it is. Cell Count is a trusted health resource, and we have the shared goal of decreased rates of Hep C and HIV inside, or we’re supposed to. So we say, “Hey, we both want this thing. You want your numbers down? So do we.”

Is that even more so during COVID? Especially since you haven’t actually been able to go in physically.

There’s a huge amount of distrust around COVID, because, well, the government is responsible for their incarceration. And a lot of folks have bad experiences with healthcare. They might be overprescribed, or they’ve been denied their HIV meds when they change institutions and their care gets interrupted. That’s gonna build a lot of distress and frustration. So when the same healthcare staff come tell you to get vaccinated, or wear a mask, people are going to be like, what? No, we have absolutely no trust towards you.

Any advice to people looking to do similar work?

Make connections with people inside. If you see a writer that you like, or an artist, reach out to us. It could just start with a letter to a couple people or just one person inside. Start to build relationships, get that perspective first. Trust is such a huge thing with people inside, because their trust is constantly being violated.

Find out what people are wanting to see and what they need. Also, artists love having their work shown, so offer exhibitions or a way to display their artwork. Start volunteering to take phone calls for their hotline. That’s an amazing way to make connections with people, to talk to folks over the phone.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I’m out on parole, standing at a busy intersection. There are flying cars now. The once familiar traffic lights are nowhere to be seen. I’m terrified of violating my parole conditions by crossing at the wrong time, (I am serving a life sentence, after all). Come to think of it, I could just as easily get killed by a drunk, (flying car), driver. Life, indeed… is full of possibilities.