WHEN asked, Gord would say he was from Haywood, on the upper plains, north of where the river forks. Truth was, he collected his mail in Haywood. It’s where he got hammered most weekends. But he’d always resided outside the town limits. On orphaned parcels of land that, like Gord Bukowsky, didn’t fit comfortably in clusters.

“I’ve always favoured property along unpaved roads,” he’d been heard to boast.“Places where the buses don’t run.”

“Where the buses won’t run,” Teresa, his newly minted wife, liked to add. She wanted him to sell the cabin so they could move into town. Closer to family and friends. To her cashier’s job at the muffler shop.

“We should join the human race,” she said. “Up here, it’s like we’re outside, looking in.”

“Precisely,” he said.

He told her again why he wouldn’t budge, though it was hardly necessary; she could recite word for word how he felt about most matters: “I love that I can step outside and not see another house, car or person. I can walk till nightfall in any direction and not be stopped by a traffic light. How many people can say that?”

“How many people would want to?” she returned. Her girlfriends agreed.

Yet Teresa married him anyways, believing she had a lifetime to change his stubborn mind. Theirs had been a civil ceremony, the talking parts over in fifteen minutes, a few friends looking on. Dinner was the early bird buffet at the Bamboo Palace. The honeymoon consisted of a night at the Sweet Dreams Motel in Bear Creek, but the Bukowskys had been too wasted to dream, and their union had long since been consummated. They were home by noon the next day. He spent the afternoon working on his truck.

He’d inherited the cabin and five mostly wooded acres from his father, a hipster from the 1960s who’d played himself out. He promised to get the insulation in before the snow fell and fence the property in the spring. A hound, Gizmo, fifteen years and ailing, came with the place. Coyotes got the old man’s chickens.

He’d worked construction since giving up on community college. New subdivisions were popping up in every town within a day’s drive, instant neighbourhoods with fancy names like Westbridge Estates and Beach Grove Village.

“Tomorrow’s slums,” he called these developments. “They’re built with the cheapest products the Chinese can manufacture. When the warranties expire, the doorknobs fall off in your hand.”

Contractors kept him on despite the editorializing, impressed with his eagerness to log marathon hours at a non-union pay rate. Winters, the ground frozen and the work crews sent home, he collected pogey and played pond hockey.

Teresa urged him to find something steady, something year-round, but the prospect of working inside, staring at a computer screen or labouring over a stack of forms, caused him to hyperventilate. All those people around him, the same faces every day – uh-uh, not Gordie B. A hardhat, good boots and a strong back is all he needed. No ass-kissing, no backstabbing, no networking.

“Off the grid, cash jobs only,” he’d say. “Fuck the government.”

He and Teresa had hooked up after a dance at the community hall, her boyfriend away at vocational school. He didn’t like his women pale and catalogue thin, all bone and Botox pout, and Teresa McFadden, proudly plus size, did not disappoint. Her raspy voice could excite him reciting the Bamboo Palace menu: “Peking Roasted Duck, Mixed Vegetable Fried Rice, GongBao Chicken. All dishes include wonton soup and fortune cookie.”

Graffiti in the men’s washroom at the Pay ’N Save praised Teresa voluptuous attributes.

“For a private viewing,” the unknown author had scribbled, “call –”

Mysteriously, the station proprietor would apply a fresh coat of paint to the stalls before the tourists arrived. By summer’s end the message would reappear. In the middle of an argument about something else, both of them smashed, Gord wondered aloud what she might have done to win such adoration.

“I didn’t do nut’n,” she hissed. “Okay?”

Teresa’s on the phone now with her little brother Sean. He and his posse will be driving over from Murrayville to celebrate the marriage, any excuse to party. The gang from town is also invited.

“Take the first left when you get off the highway,” she’s saying. “Turn right again after the bridge, and watch for deer. Call me if you get lost; Sean can fetch ya.”

A slab of venison was sizzling on the barbecue when they arrived, a caravan of clunkers with bug-splattered windshields and bald radials, of rusty pickups and leaking camper vans. Radios booming Boyz II Men and Billy Ray Cyrus, empties on the floorboards clinking like a xylophone as the vehicles bounced up the potholed driveway.

The Haywood gang pulled in right behind them, Tom Cochrane and the Red Hot Chili Peppers at deafening decibels. A couple of beer-stained and ember-singed car seats were hauled to the firepit. The DJ at CKBC in Redman was divining rain, so they strung up a couple of tarps, just in case.

“We could see the clouds moving in on the drive over,” Sean said. “If they stay on course, it’s gonna be a soaker.”

A couple of the boys from Murrayville got to work filling balloons from a helium tank, tying them to the bumper of a jeep. They’d been boosted from a weather station.

“What’s with the balloons?” Gord asked.

In Murrayville, Sean said, “where there’s fuck-all else to do,” Blast-off was a popular bush party activity. When everyone is sufficiently numb, a name is plucked from a Montreal Canadiens goalkeeper’s mask. The lucky winner is strapped into a lawnchair attached to the balloons.

“The draw is held at midnight, the witching hour. The chair shoots up to about a hundred feet and then drifts whichever way the wind is blowing. A couple of years ago the balloons got caught on a power line and the volunteer fire department had to get our man down. Last summer another chair drifted into the hills and we never heard from the guy again. Nobody liked him anyways.”

“How do you bring it down?”

“You can take out some of the balloons with a .22 pistol or wait for it to descend on its own. Duck has calculated all the variables.”

“Duck?”

Sean pointed out a fella competing in a chug-a-lug contest, Haywood versus Murrayville.

“He’s worked out some kind of formula. You know, the operator’s weight, the lift of the helium. Basically, if the guy is big, Duck adds a balloon or two. If he’s small, he subtracts.”

“Duck some kind of astronaut?”

“Pretty close,” Sean said. “He’s the only one of us who’s passed Grade 11 math.”

Once the grub was devoured, the beer and the pot and a wide range of pharmaceuticals took over, rendering the universe askew. The magic mushrooms that grew wild around Murrayville, renowned for their potency, were being handed out like cream puffs. The host accepted congratulatory hits from bongs, snorting whatever was proffered, swigs of who-gives-a-shit, the warm summer night abuzz with rock ’n roll and fireworks left over from Halloween. By the time the moon had risen above the pines there were people passed out in the pasture and voluminous splashes of vomit on the road out front.

He staggered to a queue of beer drinkers watering a huckleberry bush.

“You from Murrayville?” he asked the guy to his left, innocent urinal chitchat.

“All the way,” the fellow replied.

“Haywood was named for all the hay you see stacked in the fields around here,” Gord said.“What was Murrayville named for?”

“Good question,” the guy said. “I’ll put it to the boys.”

Gord finished his business and zipped up. His query had inspired a heated discussion down the line.

“The majority opinion,” his new friend reported, “is that our town was named after some guy named Murray.”

He was feeding kindling to the fire when he spotted Teresa. She was with Duck, the mathematician; they were slipping into the woods. He’d always suspected she had a thing for the scholarly type.

Most men, the ink on the wedding certificate not yet dry, would see red. Not Gord. Because ever since the ‘I do’ he knew he’d made a mistake. He’d been blotto when he first went off with Teresa, and he’d been blotto when he asked for her pudgy hand. Before reciting the fateful vow he had to steel himself with some smoking dope and a few shots. Sober, the thought of spending the rest of his life with her scared the bejesus out of him. He was hoping the sentiment might be mutual.

He returned to the nuptial bed and passed out. He was roused a few hours later by Gizmo pawing at the door. The music silenced, he weaved through the snoozing bodies looking for her. What had to be said, he realized, had to be said before the concrete of their lives had set. It was like removing a Band-Aid from a hairy plot of skin: do it fast, get it over with.

Most of the townies had left, but Sean’s people were staying the night. They were passed out in party chairs and around the fire, curled up on the hoods of their vehicles, crammed into tents. He and Gizmo were the only two still standing.

A bag of mushrooms lay open between an unconscious reveller’s sprawled legs. He washed down a handful with a swallow of stale beer. He noted the knot of balloons quivering in the breeze and the unmanned lawnchair. The midnight blast-off had been aborted.

Along the footpath leading to the vegetable garden the magic took hold; his head began to whirl, his senses abandoned him. He tried shaking off the thoughts and images ricocheting like pachinko balls inside his muddled mind. The last thing he remembered about July 15, 1992, was the rain falling through the trees, pooling on the tarp, filling the ruts in the road. Gizmo licking his face like a lollipop.

The town of Haywood is a service centre for many of the hamlets in the rolling hills that surround it, unremarkable outposts like Redman and Murrayville and Bear Creek. Haywood’s busy airport likewise serves as a hub for people and things, flights landing and departing 24/7. Transport trucks and taxicabs line up on the tarmac, the drivers killing time jawing and sipping rancid machine coffee. The storm had come and gone overnight. Wind gusts had affected arrival times.

Early that morning Haywood ground control received a message from an approaching cargo plane.

“This is G717 beginning its descent.”

“G717, you are clear to land on runway two.”

“We have information that should be logged,” said the co-pilot.

“Go ahead, G717.”

“We’re at five thousand feet, and we just passed a guy in a lawnchair.”

He’d often wondered what it would be like up where the air is thin, gazing down at the world, a lonely astro traveller soaring through the cosmos. Now, aboard this flimsy backyard airship, he knew. Off the starboard the river wound its lazy way to the horizon. A small mountain lake he didn’t know existed glistened invitingly in the west. Occasionally a solitary light flickered, a cabin dweller wrestling with insomnia. Veiled under a wisp of cloud sat the dark mounds of the ancient Haywood hills.

He had come to at midday. Splintered remains of the chair were scattered on the forest floor, deflated balloons draped like drying laundry over branches and shrubbery. He recalled the craft being buffeted by strong winds and rain, then dropping precipitously, the unyielding earth rushing up to greet him. He remembered reciting a Sunday school prayer.

As to how he became airborne, he supposed he must have fallen back, succumbing to the lawnchair’s cushioned comfort. He assumed, for he could think of no other explanation, that Gizmo had missed evening chow due to all the excitement. That, driven by hunger, the dog had gnawed through the cords securing the balloons.

He scampered up a rise and there was Haywood, its junk-strewn yards and cracked sidewalks spread out like a child’s playset. A maple leaf sagged from the flagpole fronting the town hall. He followed a game trail to an overgrown logging road which delivered him some hours later to the junction leading home. An hour into his journey the sky darkened; he could smell moisture in the air. The temperature seemed to dip with the rise and fall of the road, and the trees lining his route tilted like the masts of storm-tossed ships. He was thankful for the warm coat and boots, although he couldn’t remember, it being summer, where he might have gotten them. Soon pellets of snow were swirling like black flies around his befuddled head.

As he approached the cabin he could hear people moving about inside. He peeked in the window, expecting to see Teresa preparing a meal or cleaning up after the party, but instead he was looking at someone’s grandmother, stout and stooped. An old man was piled in the corner like a sack of spuds. Had he taken a premature turn? Perhaps he’d been concussed in the landing. It doesn’t take much, he knew, to loosen a few screws.

He returned to the road. By noon the next day, under a brooding jumble of clouds, he stumbled depleted and discombobulated into Haywood. The town looked different: busier, noisier, larger somehow. He stopped at a diner he wasn’t aware had opened, sliding into a booth. He was hoping to run into an acquaintance who could explain a few things.

A beautiful song was playing on the radio, but he couldn’t place the voice. When it was over, the DJ said, “You’ve been listening to Adele.” Gord knew his music. Who the hell was Adele?

The waitress slapped down the menu and a copy of the Herald, the local weekly.

“Be with you shortly, hon,” she said. “The seniors’ special comes with soup.”

The lead story in the newspaper talked of an expansion of the rec centre. He thought nothing of it at first, but while spooning his chowder it occurred to him that Haywood never had a rec centre. Year after year the expense of such a facility had been voted down.

He’d blasted off in the early morning hours of July 15, 1992. Mushrooms harvested outside Murrayville were said to have a sensational second act, but this? According to the Herald, it was now November 23, 2020.

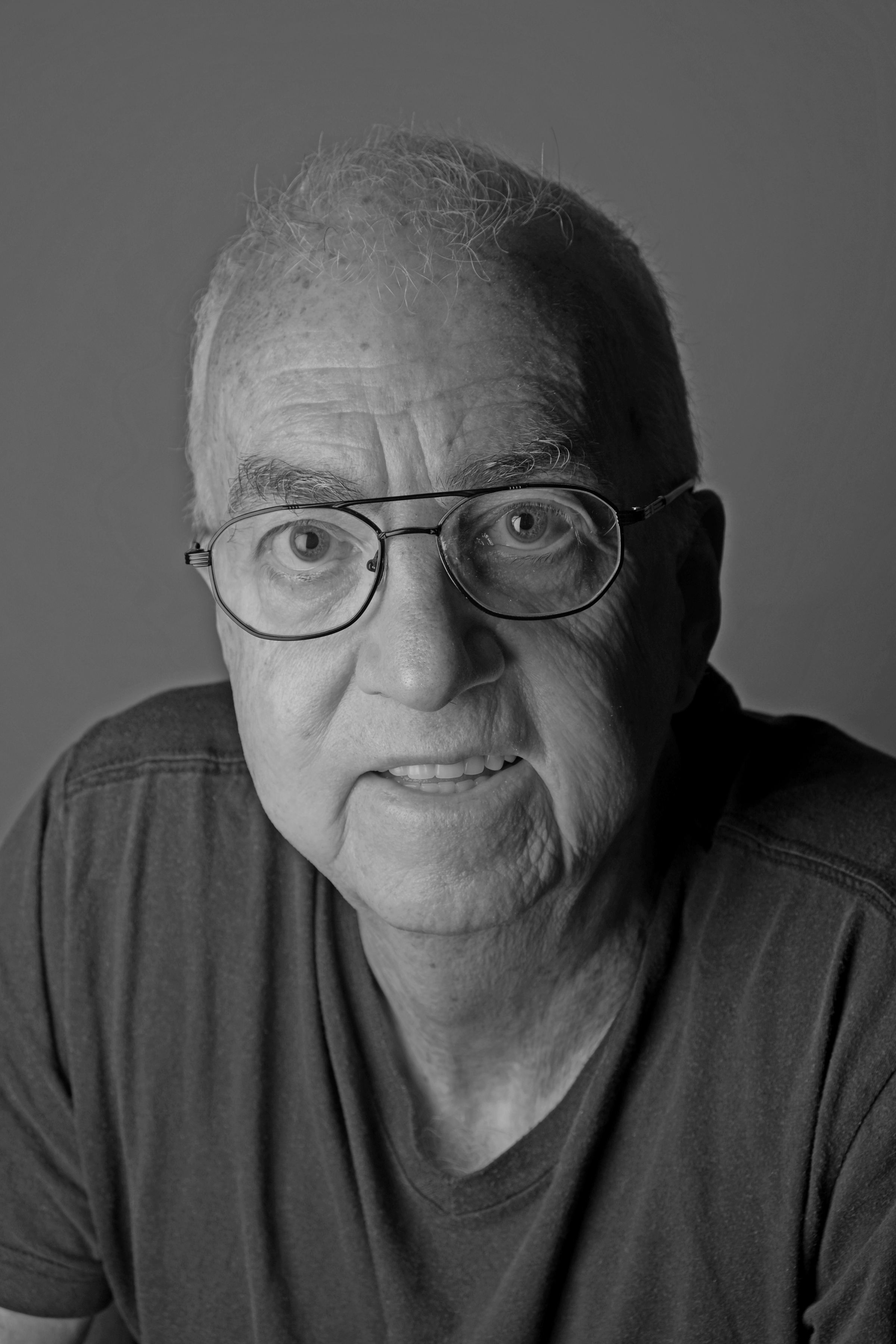

Vancouver writer Don McLellan, a 2016 Commonwealth Short Story Prize finalist, has worked as a journalist in Canada, South Korea and Hong Kong. His debut collection of short stories, In the Quiet After Slaughter (Libros Libertad), was a 2009 ReLit Award finalist. Brunch with the Jackals, his second story collection, was published by Thistledown Press in 2015.