Check out profiles of other countries in our Global Zine Report.

When zines grew more popular in Indonesia, it wasn’t just because they were an alternate creative medium. It was because, in a country where censorship is common and the distribution of information homogenous, zines offered Indonesians the freedom to access knowledge in new ways, says Annisa Rizkiana, a zinester based in Jakarta.

“Individuals and collectives that were active in the underground scene started to build embodied communities through zine-making as a form of resistance, open knowledge, and fun,” Rizkiana says. “Nowadays, youth are also so aware of the possibilities they can access in order to build more supportive communities.”

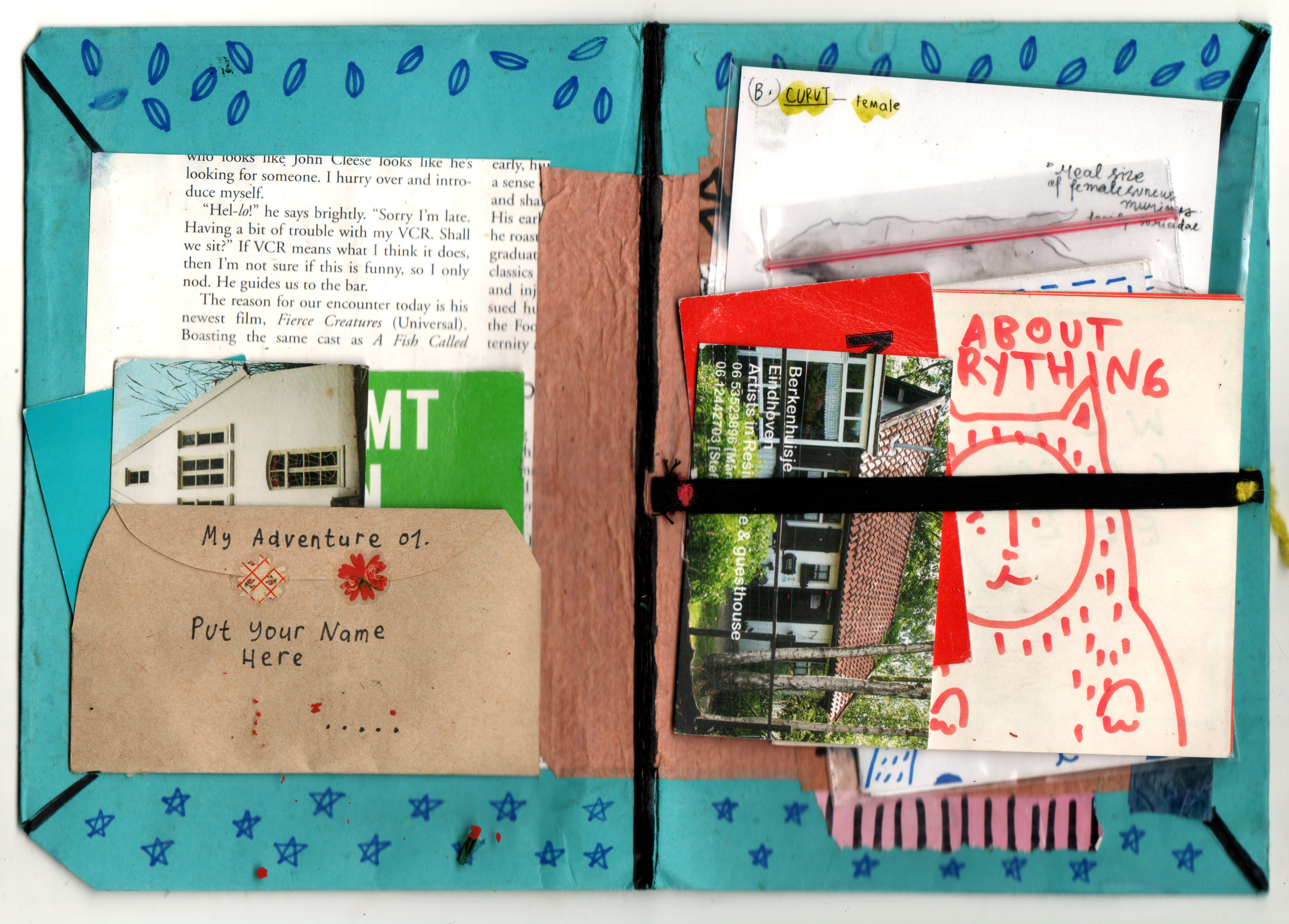

The beginning of Indonesia’s zine scene has a familiar plot: political punk bands began circulating zines about gigs and other events. The focus was music, politics and anarchy, often in Xerox black and white, according to Ika Vantiani, an Indonesian zinester. That was until the 2000s, when zines grew more popular, turning to topics such as sex, art, and film.

“The most important change is that there were more women making zines that were not only talking about music and politics, but also other topics never talked about before,” Vantiani says.

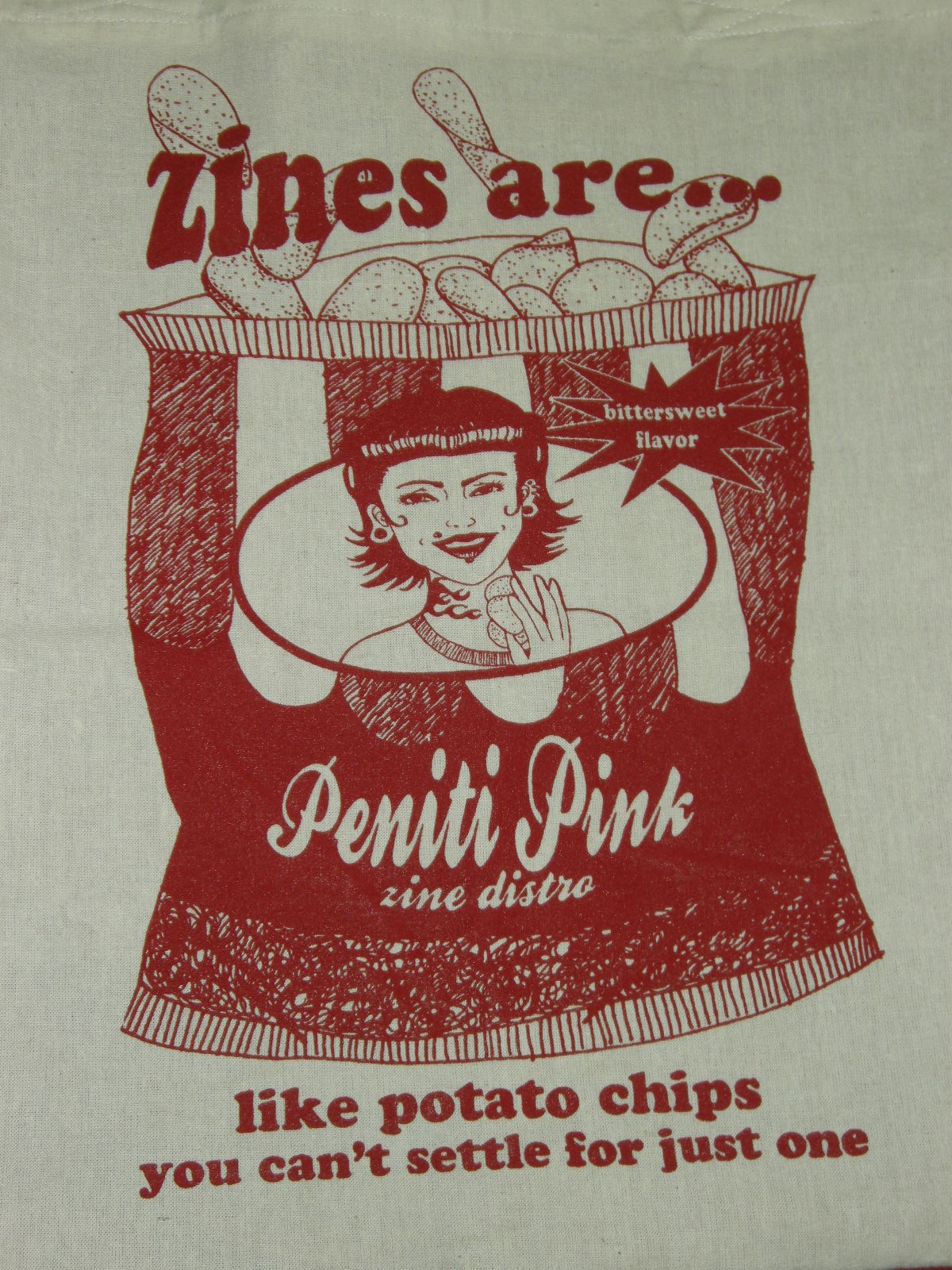

In 2001, Vantiani established her zine distro, Peniti Pink (Pink Safety Pin), where she organizes workshops and zine campaigns. “The main goal in Peniti Pink is actually to bring zines out of the hardcore and punk community,” Wawancara says. “What I experienced when I finished my first zine was so empowering that I wish for more people to experience it too. In an environment where we were told that ‘media’ means mainstream media, to be able to make our own is actually so important.”

Vantiani isn’t the only zinester to bring the zine ethos outside the underground scene. Rizkiana does zine workshops with children in rural areas. She started back in 2015, when she made zines with children about rivers and other places kids were living as a way to respond to environmental issues happening in Jakarta at the time. She started the workshops through Jakarta Biennale — an event of Indonesian contemporary arts — and Sanggar Anak Akar (a Jakarta-based alternative education model for poor children aged six to 12 years old).

“Zine-making is so liberating,” Rizkiana says, but it isn’t without its distribution and censorship challenges in Indonesia. The government blocked Tumblr — a critical platform for so many zinesters worldwide — for the first time back in 2016. Its reasoning: the website was providing the citizens in Muslim majority country with access to porn.

“Many zinesters here lost access to their digital archive,”

Rizkiana says. “We still try to sort of reclaim it back, but Tumblr-ing zines may not be the same anymore.”

CHECK OUT:

* Annisa Rizkiana

* Bandung Zine Fest

* Jakarta Zine Fest

*Sangkakalam

* Ika Vantiani