POP

Simina Banu, 72 pgs, Coach House Books, chbooks.com, $21.95

POP was more than I bargained for. Pre-release hype drew me to the collection. Early reviews and promotions pitched Simina Banu’s modern love poems and junk food references as a kind of antidote to poetry’s always-looming staleness. But blurbs celebrating the book’s spunky relevance also largely omitted what I found to be the core project of Banu’s debut collection: lyricizing the strange, suffocating experience of emotional abuse. The poems do trade in puns and punchiness as advertised, but as surprising tools that illustrate moments of gripping emotional terror.

The voice in these poems responds to the world performatively, messily, relatably. A palette of potato-chip self-care selfies rings throughout the book. Banu even thanks Ariana Grande in the Acknowledgements. (I love this.)

Digital comforts and empty calories packaged in punchy and charming text layouts offer many ways in for denizens of 2020 (if you were looking for it, by the way, you’ll find an excellent list of salty cellophane tasting notes, their letters shaped into Pringle figures, on page 15). But “pop,” it turns out, can mean a lot of things.

Banu’s adept use of pop fodder is praiseworthy. Despite being all the rage, pop references often prove tricky for lesser poets. Banu, however, earns the right to use them. She deftly pushes such images outside their natural habitats of social media slumming and crafted vulnerability, using and reusing these devices to many ends and never ends themselves.

These poems could catch anybody off guard. Shards of late capitalist culture grow less familiar and more disquieting, acting as grotesque props in a stage play of intimate captivity. A shabby shield made of Fritos, Doritos, Cheetos attempts to protect the protagonist from her narcissistic partner and their cheap digs. For their part, negging critical theory references and piercing remarks team up, a mean arsenal of counter motifs.

The partner’s jabs hurt freshly each time. But, through the poems’ deepening sense of hindsight, their grad student word salads ultimately prove to be pretty basic.

Banu’s voice, though, offers fullness and clarity. She patiently illustrates the ugliness of abuse through contrasts, repetition and transformation.

In “All of it in Theory,” alternating sentences starkly compare a laundry day spat with impenetrable clouds of jargon: “You break the silence to mention that my clothes are rags. Therefore, Derrida uses the term ‘the textual paradigm of consensus’ to denote not discourse, but subdiscourse. Your comment hurts my feelings; I eat all five cookies. The subject is interpolated…” and so on.

She hammers it — these poems tread in shades of violence. The numerous poetic forms taken by her “love poems” open endless ways to witness episodes of gaslighting, dissociation and a profound hopelessness.

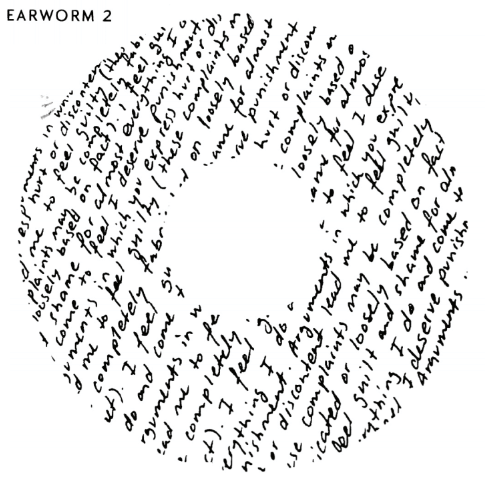

Just decipher some of the suite of “Earworm” poems, handwritten litanies shaped like spinning vinyl records, and you can’t miss the awful psychic panic: “Arguments in which you express or hurt or discontent lead me to feel guilty (these complaints may be completely fabricated or loosely based on fact.) I feel guilt and shame for almost everything I do and come to feel I deserve punishment,” reads one of these. “You offer a small kindness,” reads the next one. Yup — these are textbook examples of the cycle of emotional abuse. Oof.

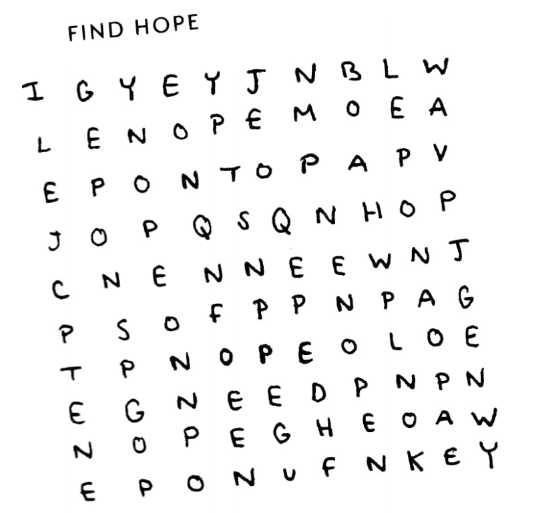

I do wonder why the rich brutality of this book has been obscured in its form, though. I can imagine being so taken with Banu’s exquisite page play that the meat of the thing gets sort of lost behind the cleverness of form, maybe. But then, these textforms and their contents are essentially molding each other on the page. Letters are arranged into pictures, games and punchlines but remain legible (oh, vispo).

I do wonder why the rich brutality of this book has been obscured in its form, though. I can imagine being so taken with Banu’s exquisite page play that the meat of the thing gets sort of lost behind the cleverness of form, maybe. But then, these textforms and their contents are essentially molding each other on the page. Letters are arranged into pictures, games and punchlines but remain legible (oh, vispo).

A memorable poem, “Find Hope,” is one in a series of word search game poems — but all a searcher will find in the grid is the word “nope” again and again. I’ve never seen a more exquisite summary of the pain and fear of a toxic relationship. What a masterful, if reluctant and painful, ability to capture those pernicious power dynamics that plague relationships, identity, and gender.

If I’m being extra, it’s just that Banu has done something so, so good here. I can only presume these poems come from her own experience often if not always. They are too tight and specific to be made-up. In POP, the poet invents and re-invents her tools of meaning-making. Perhaps this is because, having once learned to be ever-so-careful in order to survive an abuser’s intimacy, she has been left to her own devices to trust and rebuild herself in its aftermath. Am I projecting? Buy it, read it, and tell me what you think.