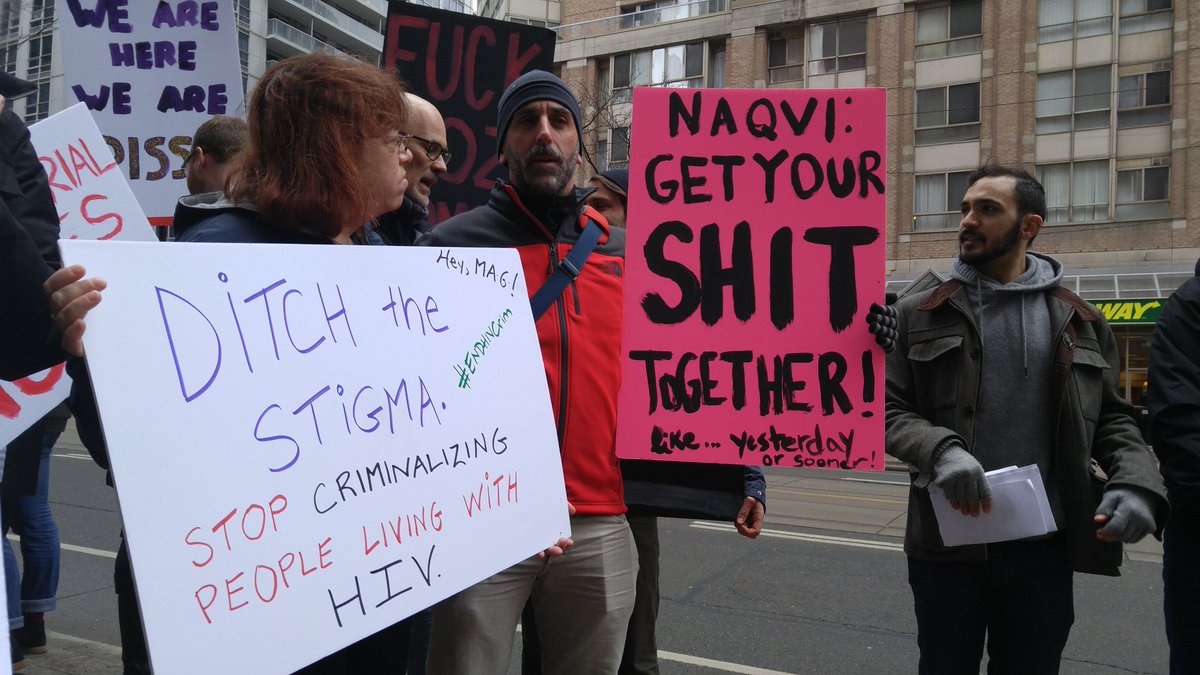

In February of 2018, I joined a small but lively band of lunch hour protestors surrounding the door of the Ministry of the Attorney General’s building on Bay St. At the time, Ontario continued to aggressively prosecute people living with HIV who hadn’t disclosed their status to sexual partners. “I. Am not. A risk when I fuck/HIV science says you better catch up,” the crowd chanted.

In February of 2018, I joined a small but lively band of lunch hour protestors surrounding the door of the Ministry of the Attorney General’s building on Bay St. At the time, Ontario continued to aggressively prosecute people living with HIV who hadn’t disclosed their status to sexual partners. “I. Am not. A risk when I fuck/HIV science says you better catch up,” the crowd chanted.

Most people who are charged in HIV non-disclosure cases have taken steps to protect their partners and don’t actually transmit the virus. In many cases, individuals know they scientifically could not pass the virus on since their treatment had reduced their viral load to undetectable. Activists had been working tirelessly on changing the province’s approach for way too long already. So we rallied to keep the pressure on.

A 2018 protest urged the Ministry of the Attorney General to stop charging people in HIV nondisclosure cases. Image via XtraIt’s unlikely that 35 minutes of chanting sealed the deal on the MAG’s eventual decision to halt new non-disclosure prosecutions in Ontario, which remains our cautious but, for now, welcome limbo reality. But the demo’s impact was also amongst the demonstrators. Between chants and speeches, we had a rare opportunity to actually hear the gruelling accounts of people who had survived such charges in their own words. Due to the issues of stigma, confidentiality and incarceration at play, many of us had never heard their stories in their own words — it was powerful.

“I was a happy and healthy family man who, every summer, would participate in the AIDS Ride for Life to raise money for people less fortunate than me living with the virus,¨a volunteer proxy read from a text given by someone incarcerated at the time. He described how his family was pushed out of their local community as a result of sensationalized media coverage and public shaming. “My future is now uncertain — housing, employment and my family life will all be subject to the stigma of HIV and being a registered sex offender.”

One seasoned activist, usually stoic, held back tears as he somberly declared to the crowd that if more people could hear the cruelty described in these stories, they might just do something about it.

One seasoned activist, usually stoic, held back tears as he somberly declared to the crowd that if more people could hear the cruelty described in these stories, they might just do something about it.

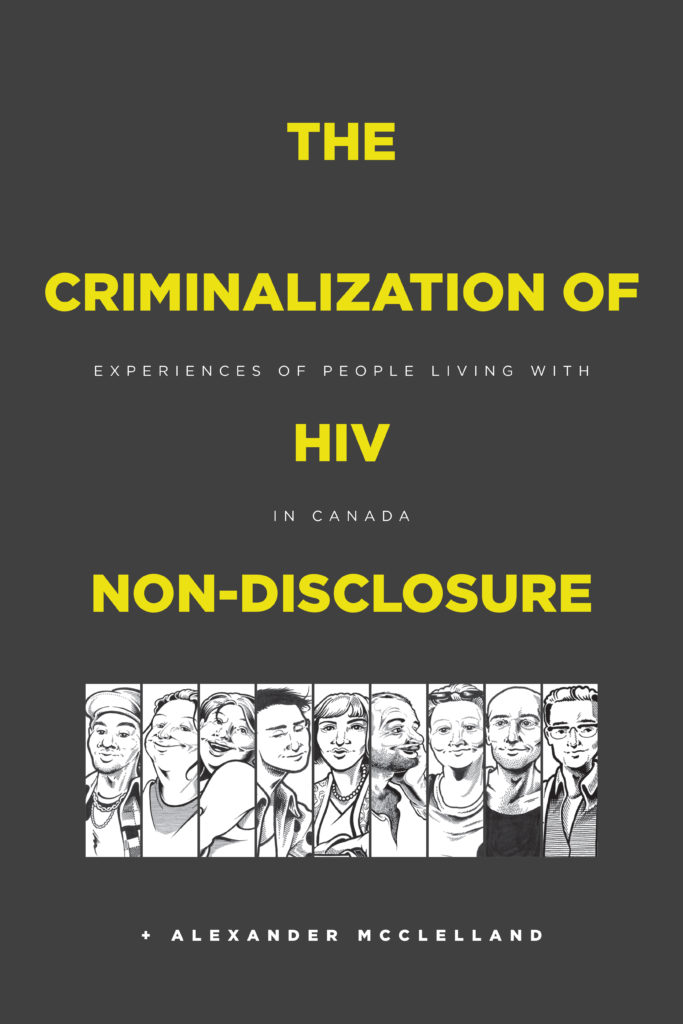

Now we have a way to do that. The Criminalization of HIV Non-Disclosure in Canada: Experiences of People Living with HIV is a research report in the form of a free zine, compiled and published by Alex McClelland, a leading researcher and advocate confronting Canada’s particularly severe approach to nondisclosure. While scholars have long studied HIV criminalization through a statistical or medical lens, the report collects nine true stories of individuals impacted by these laws, written in a straightforward and relatively jargon-free style. Each person’s story is accompanied by interpretive portraits drawn by comic artist and one-time Broken Pencil cover model Eric Kostiuk Williams. This zine is the first publication to focus solely on the experiences of real people who have undergone this process.

“Previously, all the research was focused on the negative public health impact of HIV criminalization, such as proving that it was a deterrent to testing, ” says McClelland, who produced the booklet as part of his dissertation research at Concordia. He says he was inspired by anti-criminalization activism in the US, where people who have been charged are on the front lines speaking openly about their experiences.

It’s telling that personal narratives are still difficult to find in Canada. Here, non-disclosure cases are typically tried as aggravated sexual assault. Such a conviction results in years of incarceration and a lifetime on the sex offender registry. This alone can discourage many from sharing what happened. But McClelland explains that there are also deeper societal forces that exacerbate this unjust harm. It took him more than a year to build trust with each of the nine people he profiles in the booklet, who were understandably cautious.

“Lots of them had lost complete autonomy over telling their own story.” he explains. “Most people had never had someone who wanted to hear their experiences from their perspective. Trusting people who have been labelled criminals, hearing what they have to say, that’s something that people just don’t consider.”

The stories are, in a word, gutting. Each follows its own permutation of painful and irrational episodes and long-term consequences. Together, they offer a bigger picture, revealing a complex web of institutional violence that spans far beyond cops, courts, and prisons.

After a difficult break-up, Shaun’s ex-girlfriend pressed charges for HIV non-disclosure, despite having long known his status.

After a difficult break-up, Shaun’s ex-girlfriend pressed charges for HIV non-disclosure, despite having long known his status.

When he turned himself in, the police beat him, hurled racist and serophobic slurs, and left him on the floor calling for help.

Read more about one man’s brutal experiences with HIV non-disclosure laws and media hysteria.

Chief amongst these insidious forms of punishment was constant media hysteria. In each case, the person is viciously defamed with stigmatizing and often racist or sexist news headlines.

“It was in the papers, you know they were encouraging people that had had sex with me to come forward and, like, testify against me in court,” states one of the women profiled, who McClelland names Darlene. “Now, if you Google my name, it will come up with stuff about the case.”

“People in their community read those articles, and that turned being a being shunned and beaten up. They actually experience direct violence as a result of media,” explains McClelland, noting that even those whose charges are dropped will face the long-term impact of such intense public notoriety.

“Media outlets were only interested when people were charged or prosecuted, never when someone got off or had the charge dropped. Those people still experienced many of the negative impacts of criminalization regardless.”

Indeed, acquitted or not, most people described in the report zine endured house arrest, media misrepresentation, intense stigma and ongoing state medical surveillance. The particularly pernicious role of public health and medical professionals is a refrain in the McClelland’s snapshots.

“I thought if I was taking medication I didn’t have to disclose,” explains another participant, dubbed Matteo. “Apparently, that is not the case.” A few weeks after a hookup, the police came to his work and arrested him in front of his staff and customers. At the station, he initially refused to speak without a lawyer, but eventually he broke under pressure.

“I told them a lot about myself,” he recalls. He ended up having to educate the police about the science of HIV. “They didn’t know what undetectable meant, they didn’t have any knowledge on it.”

Illustrations by Eric Kostiuk Williams

Illustrations by Eric Kostiuk Williams

Ignorance about undetectable viral load, which is universally accepted to safely prevent the transmission of HIV, abounds in particular in these stories. But more frequently, it comes up with public health workers, who tend to make the first move towards disciplining patients living with HIV by calling the authorities.

“So many people end up initially having to talk to police through public health. It ends up becoming an entry point to criminalization,” McClelland describes, who jokes grimly that HIV-positive people have never been the “public” in public health. “In most cases, public health was a surveillance and coercion tool more than anything… A lot of people understood it as just an arm of the criminal justice system.”

Parallels between the wildly inconsistent American context and McClellands findings reflect the complexity and scope of the issue says Trevor Hoppe, author of the book Punishing Disease. Hoppe joined McClelland in Toronto recently for a packed evening launch and accompanying symposium the day following.

“Media outlets were only interested when people were charged or prosecuted, never when someone got off or had the charge dropped.”

“Stigma fuels this impulse to punish people we think are different from us in any way. There’s knee-jerk reaction to put those people in prison,” Hoppe offers.

Hoppe makes a striking comparison to show what he means: on the one hand, look at society’s deep-seated contempt and fear towards HIV-positive people, who are often poor, racialized, queer or somehow seen as deviant. On the other hand, look at the dignity and non-interference enjoyed by the largely white, middle-class mothers pushing a potentially catastrophic ideology against vaccinations. It’s easy to see — a host of prejudices bolster the government’s emphatic scrutiny towards people living with HIV.

Ultimately, for as many strains of analysis and interpretation one can draw from the horrors chronicled by McClelland, to linger there for too long would be equal to missing the point.

“This publication is a chance to have these people and stories stand on their own, and act as a counter to the way they’ve been talked about,” confirms McClelland, who will be publishing other findings from his research through more traditional academic channels. “All the zine needs is for people to listen and understand; And, I’d add, for people who are working in HIV or healthcare to consider the impact of their actions and reason they may act in a given way, and on whose behalf.”

As rigorous and well researched as this project may be, McClelland’s zine asks the same as any other zine — that its reader receive and carry each of the stories as they are, in all of their complexities.

Alexander McClelland’s zine is available in its entirety on his website. Portions of the accompanying conference can be watched as a video here. To learn more about the criminalization of HIV in Canada, you could start by checking out the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network.