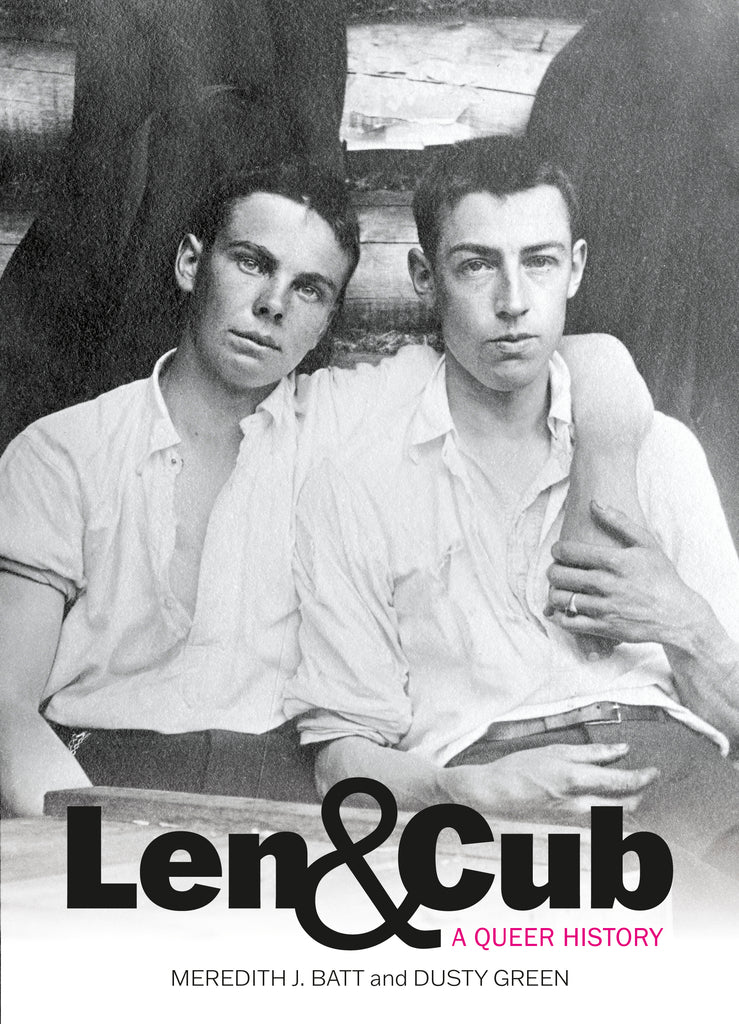

Len & Cub: A Queer History

Meredith J. Batt and Dusty Green, 167 pgs, Goose Lane Editions, gooselane.com, $24.95

Two boys sit in mid-distance, facing the camera head on. Though the still-bare tree limbs behind them suggest it is early spring, the day must be warm, for they are shirtless, their pale chests and bare arms lean and ropy with muscle. The intense snub-nosed boy sits in his lanky friend’s lap, one arm slung around his shoulders. The buttons on his trousers are undone, and the other boy’s leg snakes under his. Their loosely clasped hands touch, the gesture something between a handshake and a caress. They squint beneath the sun’s glare, unabashed by their proximity.

The result of painstaking research beginning in the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick (PANB) and stretching through Maine, Quebec, and Vermont, Len & Cub is a labour of love.

Its subject is a historical record of love between two young men who lived in early-twentieth-century rural New Brunswick, Leonard “Len” Keith and Joseph “Cub” Coates, that would otherwise remain unknown, locked away in a cardboard box in a climate-controlled facility. Instead, thanks to the diligent work of queer historians, these images are now in your hands to be flipped through like a family photo album, offering slivers of time rich with detail: a lazy afternoon smoke in a shared hammock, skating on a frozen pond, pre-deployment days in a First World War Canadian military camp.

Archives are miraculous things, swallowing up random bits of the world and holding onto them until the right person happens to stumble along. In this case, the right people were Meredith Batt, an archivist at PANB, and Dusty Green, who has since founded the Queer Heritage Initiative of New Brunswick, an archival and educational institution that aims to preserve records of queer history in the province. When Green found a collection of photographs showing a same-sex couple in a relationship spanning many years, he and Batt worked as a team of sleuths to discover the story of what they came to think of as “our boys” — a story of queer kinship across time, since for the authors, finding evidence of early queer relationships in rural Canada was nothing less than an existentially affirming act.

That this book even exists is a miracle. Consider all the things that had to go right before these images could end up in the Provincial Archives: the photos had to be taken by Len, preserved throughout his life, held onto by his sister, purchased at an estate sale, and donated to the archives by their new owner, who identified the men in the pictures as “boyfriends” to the archivist. Finally, a sympathetic viewer who understood the profundity of what they were seeing had to come along, find the photos, and decide to do more than bury them in an academic journal citation.

This is not to say that Len & Cub lacks rigour — the authors bring great care to the subject, contextualizing the photographs within early understandings of queerness to avoid imposing contemporary standards onto the boys even while they work with all available documentation to draw plausible inferences from the suggestive gaps and silences in the visual record. This is a calculated risk, but there is no other way to tell the story of people who could have never publicly expressed their true feelings in their own time and place.

This is a remarkable book and a work of public-facing scholarship in the purest sense. It takes something from behind closed doors and shares it with the world to change how we understand those that came before us and our own relationship with the past.