I was twenty-five years old the first time I tried growing a beard. We were living on Brunswick Street in a slanty shanty. The floors in the apartment were slanted. The whole structure of the apartment was tilted. You could put a marble on one end of the floor and it would roll to the other. You could follow it from the entry at the top of the stairs down the hall to our bedroom. Mice would come into the kitchen while we slept.

I started on the beard a few months after I got bounced from the Naval Officer Assessment Board in Victoria. My military career seemed to be going nowhere quickly.

Every other week, I’d call the recruiting centre.

Yes, they’d say, your file is still on track. You can expect us to call you any time now.

Then I’d take the bus to the call centre. Sasha would stay home with the mice until eleven and then bicycle or take a taxi to the restaurant in time for the lunch shift.

Consider how it came to be: four years out of University, used to be on the Dean’s List andeverything; sitting on a creaking, cold city transit bus to go answer phone calls for ten dollars per hour.

The day I decided to grow a beard started just like that.

As soon as I got to the call centre I went to the sign-out counter.

It was Katarina. I’d had a crush on Kat for as long as I’d been working there. She had green eyes, short blonde hair, and a tattoo of a dolphin on the back of her neck.

Morning, Kat. How’s everything?

Still here, right?

Any chance you have a leave early in there for me?

Kat turned to her computer for a sec.

You can put your name in the book. It’s pretty slow right now.

That’s the best thing I’ve heard this morning.

Glad I can help.

I went to the computer I usually used, signed in, and entered my password into the phone. Immediately the red light came on.

You can go home Jay, Kat said through my headset.

Thanks. You’re wonderful.

And she was. It was seven-thirty in the morning.

Even though it was minus ten degrees and snowing outside, I decided to walk home. After all, I had the entire day to kill.

The walk across the bridge was brutal. Snow and ice pellets stung my face.

Maybe that was the germ of it.

By the time I got downtown it was still too early to go home respectably, so I went to the library. I’d already read one of the national papers, but there was still the other national paper, as well as the local papers.

“Read Admiral Collette assigned to lead investigation into submarine mishap.”

There was a picture of the Admiral in his dress uniform, festooned with medals, looking stern and eminently competent.

He had a beard that covered nearly half of his face.

I remembered seeing the Admiral in Victoria in the fall, during the last day of the Board. We were in an auditorium. I was cripplingly hung-over, nearly asleep in my chair.

When the Admiral walked into the room, the whole place seemed to straighten in their seats and let out a breath.

He was not a tall man, slight in stature, but with unmistakable confidence as he took the podium. He thanked us all for coming, and said it was a great pleasure to meet such a dedicated group of smart, young people.

The beard made him seem all the wiser and more experienced, while at the same time more the everyman. It was a beard that caused you to hold the face behind it in a kind of awe, but also made you feel immediately at ease.

At the reception after the presentation I’d hovered around the Admiral, as several of my more go-getting colleagues chatted with him… about Victoria, about different classes of ships, about life in Canada’s Navy. I’d wracked my brain for something clever to say but was ultimately very relieved when he moved from our group

over to another.

About an hour or two later I was told I hadn’t made it into the Navy but that there was a place for me in the Army if I was still interested.

Yes, yes I was.

After a couple of hours in the library I made my way to Timmy’s, spending my last five dollars – bus fare and snack money – on a hot chocolate and donut. When I could nurse those for no longer, I stopped by the used records shop and then the used book store, and finally our apartment.

Sasha was sitting on the step inside our front door.

You’re back pretty early.

Slow morning. I figured I’d come home, and then go to the gym. I’ve got to be in fighting shape in case the recruiting centre calls.

You know what you could do while you’re waiting like this? Get your drivers’ license. I’m waiting for a taxi because no bus will go out to the Lincoln Road at this time of day so I can serve lunch, only the cabs are forty minutes getting here because of the snow. You’re twenty-five years old and you don’t even know how to drive.

Unbelievable, right? It’s not like we can afford a car, anyway.

Yes, but when we can it would be nice if you could.

Then her taxi pulled up, headlights brightening the falling white.

See you tonight.

The wind gusted the door shut with a bang.

I went upstairs into the slanty shanty. My feet, hands, and face were totally numb. I put on some coffee, and washed the breakfast dishes. Then I took out the phone book and called Young Drivers of Canada. They had lessons starting this weekend. Yes, they accepted MasterCard.

I thought about going to the YMCA to hit the treadmill and use the weight machines. I’d been a bit negligent with that lately.

The wind swooped and howled around the apartment. Outside the street and sidewalk looked increasingly impassible. I lay down on the mattress with the idea of closing my eyes for just a couple of minutes. Instead I slept for nearly ten hours.

When I woke up, Sasha was in the room using the computer.

When did you get home?

Around four. We closed early. Pierre drove me home.

Nice. Pierre’s the gay one, right?

Not that I know of. What’s that on your face?

Did you forget to shave?

I’m growing a beard.

Good luck with that.

You know how NHL players don’t shave during playoffs? It’s the same kind of thing.

Have a good sleep.

I signed out early from work again the next morning, and again walked home. The roads weren’t too bad. It had warmed up in the previous evening and the snow had started to melt. Sasha’s bicycle was gone from the landing of the slanty shanty.

I went upstairs and opened a beer. It was officially the weekend.

The driving lessons were OK, apart from having to be in class from eight-thirty until two on both Saturday and Sunday. You had to take the classroom lessons before they’d let you use one of their vehicles.

The instructor was a smooth-faced education student named Walt. My fellow learners were mostly teenagers. There were a couple of recently-arrived Asian immigrants who knew how to drive from their home countries but wanted a break on car insurance here.

I was possibly the oldest person in the room, and definitely the only one with a beard.

Walt went around the room asking us why we were taking the course. The teenagers wanted to get to and from the mall. Some of them worked there. One of them said he hoped it would help him meet girls.

Jay, why do you want to learn how to drive?

I want to please my wife.

Everybody chuckled.

I also want to get lower insurance rates.

Walt nodded. He agreed with me. He agreed with all of us.

I know why you want to drive…why all of you want to learn to drive. It’s one of those things that make you an adult, right? If you’re a grownup you have to know how to drive.

Nobody disagreed with him.

It was hard to stay awake in those lessons. I managed to get a score of 72 on the final quiz on Sunday. A 70 was required to pass. I booked an appointment with a Young Drivers car and instructor for the following Monday.

Over the next week things were alright. I didn’t oversleep. I stayed for nearly all my shifts at work. I hit the gym nearly every other day. Clearly this was an enterprising young man who was going places.

When a caller at work got on me about the price for a car rental in Tuscaloosa or Stone Mountain or Cape Canaveral in three months’ time, I would take the microphone of my headset and scratch it against the scruff of my beard until they hung up. Doing this a couple times in a shift made the job suddenly become far more tolerable.

On Friday the Army called. They wanted me to come in on Monday to update my physical and medical tests.

You’re very close to having an offer, the Corporal said.

That afternoon I told HR that I was done working at the call centre. They were looking at the newest member of the Canadian Armed Forces. Infantry Officer. The girl I spoke with at the counter didn’t look all that impressed. I tried to find Kat to tell her but she’d taken the day off.

Back at the slanty shanty, Sasha seemed relatively pleased when I told her.

Just so long as you can actually get it this time, she said. What’s it been, a year and a half since you first went in there?

It’s been something like that.

You can get back on at the call centre if you have to, right?

It won’t be an issue.

She raised her eyebrows at that, but didn’t press it any further.

I stayed sober all weekend, laid low in the slanty shanty, watched DVDs of old TV shows, and went to the gym.

There were lots of plans. The opening salary of an army officer was forty-two thousand dollars per year. To me that seemed like an awful lot of money. Good-bye slanty shanty, good-bye student loans, hello home ownership, winter vacations in the Dominican, and at minimum one late-model car in the driveway.

It was nearly twice what I made booking rentals… to say nothing of the prestige.

Monday morning I shaved the beard. I was vaguely surprised to see my old new face. It must have taken five years from my appearance.

Who was this hard-charging, eminently competent young man?

Second-lieutenant Jay Stevens, at your service. Let’s go boys. Fan out. Let’s stomp the shit out of those Taliban.

I called Young Drivers and cancelled my lesson for that afternoon. Assuming the Army wanted me to report to Basic right away, I wouldn’t have time to complete the lessons.

I splurged and took a taxi to the recruiting centre.

The med test was fine.

The interview was fine. The Captain was short, wiry man in his early forties with wire-rimmed glasses and a neatly-trimmed mustache.

You had a rough time of it in Victoria, but we’ll get you into the Forces yet. We’re very close to having an offer for you. Just go in there and nail the physical.

I blew the physical by two pushups. Everything else was good. They said I could come back in two weeks and try it again.

I didn’t say anything to the Corporal at the desk on the way out.

Sasha was waiting for the news at home. I walked downtown slowly, trying to figure what to do with the rest of the day and the weeks that would follow. I wondered if I’d be able to get a partial refund on the driving lessons.

Snow started to fall on the narrow street in heavy wet flakes.

Matthew Stranach is from Fredericton, NB. He currently lives in Qatar, and is working towards an Ed.D in Educational Technology through the University of Calgary. Matt’s writing has appeared in Strange Horizons, the Rumpus, Salty Ink, and elsewhere.

Matthew Stranach is from Fredericton, NB. He currently lives in Qatar, and is working towards an Ed.D in Educational Technology through the University of Calgary. Matt’s writing has appeared in Strange Horizons, the Rumpus, Salty Ink, and elsewhere.

He is Kai and Ethan’s dad.

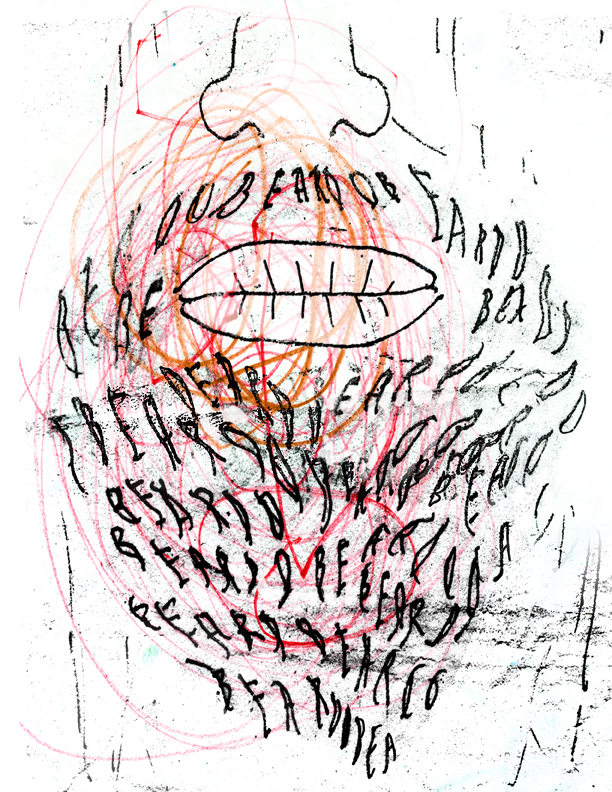

illustration by Melissa Luk

The proudest moment of my young espionage career was Operation Secret Crate. One Saturday afternoon, Mom drove up with my brother and his friends, who were coming over to play Grand Theft Auto, make stupid jokes and eat junk food. My mission: eavesdrop.

to the distant Lake Nipissingue, the other to the Chats. Mr. Fisher set off to enjoy himself in Montreal, Mr. Francher, the accountant, being appointed locum-tenens during his absence. Another young Scot and myself, together with two or three non-descripts, formed the winter establishment. Having just quitted the scenes of civilized life, I found my present solitude sufficiently irksome; the natural buoyancy of youthful spirits, however, with the amusements we got up amongst us, conspired to banish all gloomy thoughts from my mind in a very short time. We—my friend Mac and myself—soon became very intimate with two or three French families who resided in the village, who were, though in an humble station, kind and courteous, and who, moreover, danced, fiddled and played whist.

trance into Alabama, has been intimately connected with all our state operations, educational and missionary, and no man among us has been more successful as a church financier. He has bestowed special care upon the education of his children, all of whom he has reared for the most part without their mother’s aid, as she died when they were young. The Dexter Avenue Church building was constructed under his leadership.