THIS FALL, Oscar-winning rapper Common is branching out. Menswear? Aftershave? Watches? No, the popular Chicago culture maven is moving into webcomics.

Once the stuff of charming LiveJournal pages, the webcomics game has grown into big business, so much so that Common and business partners now hope to use the industry’s growing popularity to tell the story of “globe-trotting antiquities dealer” Caster Common. Naturally, there will be a soundtrack by the man himself, and the plan is to harness the comic’s anticipated popularity and move from the small screens of phones everywhere to a full-on live-action movie.

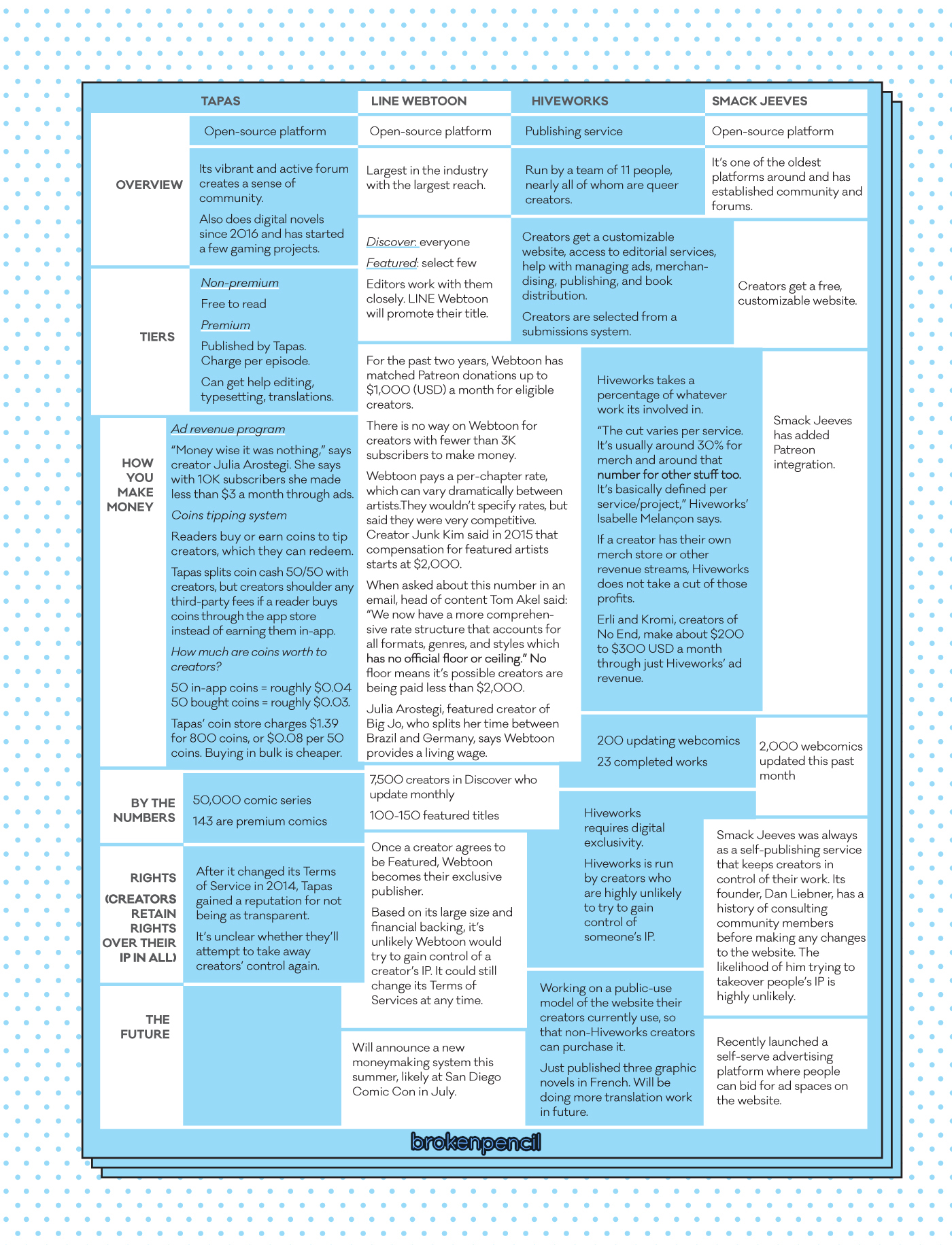

Common’s comic is going to launch on LINE Webtoon, a Korean-based digital comic publisher and platform. With 10 million daily visitors, Webtoon is the latest and fastest growing entry into the expanding world of online comics.

Read More: Want to make your own webcomic? Creators give advice

It’s all a far cry from the webcomics world we knew a decade ago. For readers, these changes mean there’s now a seemingly infinite, scrollable buffet at their fingertips. For creators, it can mean greater autonomy, more ways to monetize and far more platforms to choose from.

But once something can be monetized, it’s a bit like blood in the water — a whole lot of hungry people start showing up, including multimillion-dollar corporations (in 2014, Amazon bought mid-sized player ComiXology) and big names looking to cash in.

***

A decade ago, webcomic creators often had to choose between either being wholly independent or tied to a publisher. Each came with its own set of struggles: independence can mean having to hustle like hell, and working for a publisher opens you to possible exploitation.

However, a growing online economy created a grey area, says Isabelle Melançon, lead editor at webcomics publisher Hiveworks. Suddenly, indie creators could make money off of ads, and tools began cropping up to help them “monetize an idea without compromise,” she says. (Hello, Kickstarter, Patreon, Ko-fi, et al).

Melançon says one critical change is that artists are now in a better position to understand their rights and take control of their distribution. It has never been so easy to go independent, she says, though it’s not necessarily the right choice for everyone.

“It’s an ecosystem, and most of the creators have to bunch … different things together to have their monthly salary,” says Melançon, who’s run her webcomic Namesake for seven years now, also hosted on Hiveworks.

“If you have one revenue source, you buckle pretty fast, because diversification is the order of the day.”

Hiveworks tries to help creators with their diversification by offering a range of services — services that used to be the exclusive domain of publishers — while allowing creators to retain their intellectual property (IP) and creative freedom. This includes help with managing ads, web hosting, merchandising, and publishing.

LINE Webtoon — arguably the biggest platform in webcomics right now — only entered the English-speaking market four years ago.

Launched in 2005 by the South Korean NAVER corporation, it’s an app-based open platform where creators can self-publish. (NAVER is basically Korea’s Google. It’s a big deal.) After NAVER refined its model in Korea, it exported it globally in 2014. Tapas, formerly known as Tapastic, is another popular platform based on this same Korean model.

Format is key to Webtoon’s popularity. There’s a reason it’s called “Webtoon,” not “Webcomic.” Webtoons are similar to webcomics, but there are some important differences. While a webcomic’s chapter usually takes place over multiple pages, webtoons are usually one long, vertical strip. If you’re looking at one on your smartphone, it makes for an easy, scrollable reading experience. Some even have animation or soundtracks that play as you scroll.

They can be quite beautiful.

And while you can certainly find traditional webcomics on Webtoons, Tapas and other competitors, the big headliners tend to be webtoons, especially ones illustrated in the manga-style.

Webtoon and Tapas’ strong mobile presence and ability to tap into a new generation of readers are part of what’s made them so successful, says Dan Liebner, the founder of Smack Jeeves, one of the oldest free webcomic hosting services around.

Like a decade ago, the majority of current webcomic fans are young women aged 14 to 24. But young readers today have grown up in a world of smartphones, Liebner says, and are more likely to read a webcomic on their phone than their computer.

Since he started Smack Jeeves back in 2005, Liebner says the industry’s become much more competitive, especially since Tapas and Webtoon showed up.

“It was more of an indie community,” Liebner says of the early days. “There weren’t really any big corporations with lots of money and space.”

Now, “these companies have millions of dollars in their budget and I’m basically barely getting by trying to compete with them.”

Smack Jeeves is essentially a one-man show, with more than 2,000 active comics. But page views have inevitably gone down with more competition in the market. Smack Jeeves’ web traffic peaked in 2012, and is now is down by a third. Liebner’s focus is on the comics, but to funnel money back into the website, he’s built a self-serve advertising platform that allows people to bid for ad spots on the site. It was launched in April.

It’s undeniable that the market is more competitive, but to George Rohac, that’s a good thing, because it means fewer barriers to entry. Rohac’s been involved in webcomics for well over a decade, and was named an official Kickstarter Expert by Kickstarter. He helps manage webcomic creators’ projects and careers through his company, Organized Havoc.

He says setting up, customizing and hosting your own website was once a huge barrier for those without coding skills. Now, with Squarespace, Webtoon, Tumblr and Hiveworks, it’s easier for creators to focus on their work rather than struggling with website troubleshooting.

(Fun fact: Rohac has worked with Alexis Ohanian, who is married to Serena Williams. Therefore, by virtue of this interview, I am now three degrees of separation away from the greatest athlete on the planet — that’s how it works, right?)

Fewer barriers to entry of course means the market has grown — and quickly.

“That, in my opinion, is good,” he says, because it’s meant a greater diversity in both content and among creators.

In the early 2000s, webcomics largely rotated around heterosexual, cisgender white men playing video games. Now, at least in the U.S. and Canada, there’s a larger variety of stories and subgenres. That being said, manga remains king of most top 10 lists.

Creators Rights

Webtoon and Tapas are popular and easy to use, but the thing about open platforms is that a creator’s rights over their own work aren’t always safe.

In April 2017, Tapas added a “Right of First Refusal” clause to its terms of service. Basically, if someone approached a creator who uses Tapas about acquiring their intellectual property, Tapas would be able to block them and ask the creator to give it the same offer first.

This was poorly received, and Tapas removed the clause within a month, claiming they wanted to protect creators who were taking bad deals with predatory publishers. Some community members still saw it as Tapas’ way of preemptively locking down any potential stars that rose on its platform.

“Fortunately the entire (web)comics community raised hell,” Erli and Kromi wrote in an email.

Erli and Kromi, the creators of No End — an LGBTQ+ themed post-apocalyptic webcomic — say the move “left a bad taste” in their mouths. Since they launched their webcomic in 2014, the Finland-based pair have used platforms Smack Jeeves, InkBlazers and Tapas. They were in the process of moving over to Hiveworks when the terms changed at Tapas, and as a result, sped up their launch with the publisher.

In the case of Tapas, backlash seemingly forced the company’s hand. Does that mean we live in an age where public ire can keep open platforms accountable?

Rohac isn’t convinced.

“There are still so many bad actors,” he says, who consistently underpay creators, or don’t pay them at all. “You can do terrible, reprehensible things to people and their IP and still keep on doing things in comics.”

That being said, Rohac still sees open platforms as a viable option for creators — people just “need to keep on their toes.”

Melançon of Hiveworks’ sees open platforms more neutrally, as a part of a greater ecosystem.

“The most important thing to remember about them, no matter how you feel about them … whether positive or negative, is that they’re necessary,” she says, because open platforms are needed for creators to incubate their talent, learn and form bonds.

The Platforms

For aspiring creators, which platform is best for you depends on the scope of your work.

For creators who want to do a short-form comic on a casual basis, platforms like Webtoon or Smack Jeeves are good options, because they take little initial effort. If your comic is a gag-a-day that’s shareable, Rohac also recommends Tumblr (just make sure you put your links on the image so people can trace it back to you, he advises).

However, if you want to create a longform comic with the goal of it becoming your main gig, consider making a greater initial investment, Rohac says. That most often means having your own website, which gives you more options for making money and keeps your IP within your grasp.

For creators who can’t code, there aren’t really any good website templates for webcomics right now, he says. Hiveworks, though, is addressing that gap in the market by working on a version of their platform that can be purchased by those who want to be completely independent. Rohac, who’s used the backend, known as Comic Control, says it’s his No. 1 recommendation once it comes out.

Until then, open platforms, though not perfect for webcomics, are a decent choice, he says — that is, until they go “poof.” To some readers, the idea of Tumblr going “poof” may seem ridiculous, but take a moment to think about it. How many of the websites that you use regularly now, existed 10 years ago? And how many of the sites you used back then, are still popular or even alive now? (RIP Friendster, Myspace, MSN chat.)

DrunkDuck, for instance, used to be the leading webcomics platform, with 95,000 members posting comics in 2010. Unfortunately, its popularity has taken a hit since then.

We’re in an age when tens of thousands of webcomics publish daily on platforms that didn’t even exist five years ago. It’s difficult to predict which of these platforms will remain and which crumble in the coming decade. Harder still is to know is what the spirit of the industry will be like in the future. Will sustainability and equity be prized, or will clicks and celebrity-brand spinoffs be at the forefront? If you ask me, it’s up to readers to do their part. Support the creators you love so that they can make choices based on what’s best for them and their work — not simply to survive.