By Sarah Speight

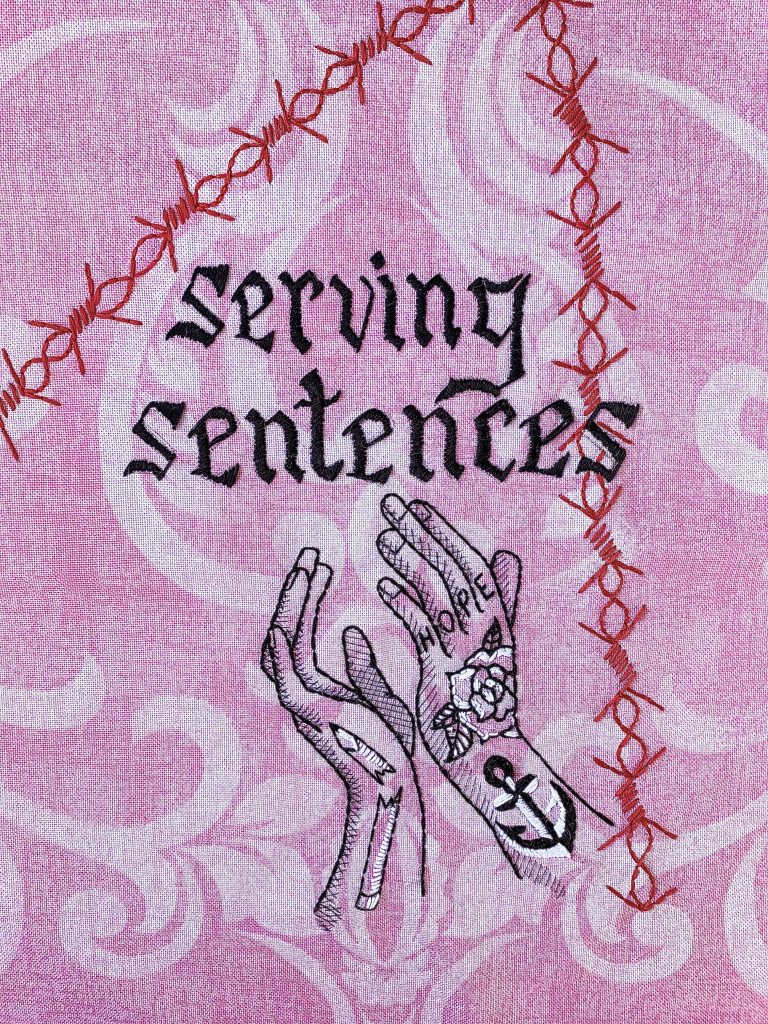

Feature art by Amy Scarlett

In March 2020, for the first time since opening, the phones at the JAIL Accountability & Information Line (JAIL) went quiet. JAIL began with little more than a phone line and a lot of guts. Since opening three years previous, we had been consistently slammed, fielding thousands of calls every year from people imprisoned at the Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre and their advocates.

The telephone is the foundation of our collective’s work. It’s a lifeline for people on the inside, many of whom can find no support elsewhere, and the primary channel of communication for us to organize and confront rampant human rights issues inside. The familiar ringing sound filled the room every weekday afternoon, a constant reminder of why we were here. So, you can imagine how caught off guard we were when it stopped completely. Access to phones in prison was obliterated early in the COVID-19 pandemic, and even now has yet to fully return to the level it once was. The past two years have been an especially terrifying time in Canadian prisons, with scant information coming from outside, and even less sympathy from the people and powers running the facilities. Both federal and provincial prisoners have spent an extraordinarily large portion of their time under lockdown — actual lockdown — since the beginning of the pandemic, whereby basic services and supports are arbitrarily suspended for days on end. Unable to leave their cells, people inside had no access to the phone at all, let alone secure time to call us when their loved ones were also anxiously awaiting word of their safety. In that quiet room, and on Zoom, our tiny team worried for our friends inside. How were we going to stay in contact with folks under these new restrictions? Information was unstable and hard to share, and folks were stressed out, to say the least. How could we help keep people updated on what was going on with COVID?

We managed to reach a few of our people inside with an idea — how about we use print to stay in touch? They liked it, so we put together the first issue of the Innes Road Gazette, a print zine full of COVID updates, news, contact info, and of course, a call for submissions. At that point, we had been operating the hotline for over a year and had sent countless pieces of mail inside. We were confident about navigating the jail’s mailing rules and incredibly careful to ensure our first edition made it into people’s hands. This meant no tape, staples, glue, stickers, crayon, paints, or markers could get near anything we were sending in.

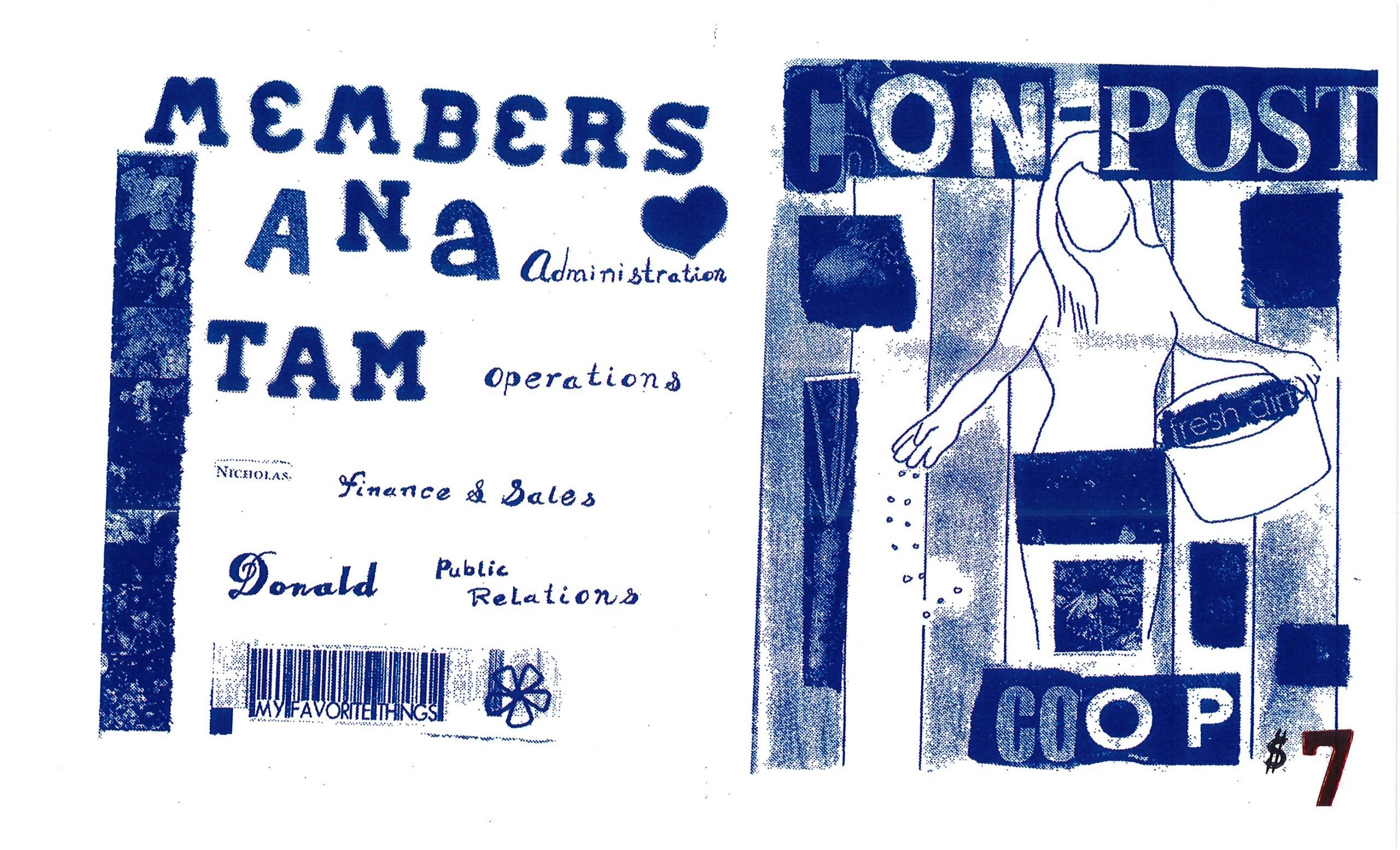

An image from Innes Road Gazette #1

An image from Innes Road Gazette #1

We anticipated that one of two things would happen. Either we would get a giant stack of mail full of creative, thoughtful content from folks inside, or we would get a giant stack of mail stamped “return to sender”, issue #1 rejected. Instead, what happened was… nothing. We waited, but our mail was empty. Eventually, prison phone privileges slowly began to return. A few months after mailing the zine, we finally got some intel from a friend on the inside. They had received the notice saying that mail had arrived for them, they explained, only to discover it was being held until their release without explanation. Then we got another call — same story. And another. The phones, it seemed, were beginning to open again, but now it was our zine that had been blocked.

The experience was frustrating, but it’s all too familiar. One can do everything “by the book,” and the jail’s censors will still put up barriers. As always, we were left with burning questions. Was the title too political? Did we use too many images? What the hell happened? Even long-running prison zines like Cell Count, published by PASAN, are still frequently barred from Canadian jails and prisons by Visits & Correspondence staff, who screen all mail. Similarly, the zines that the Prisoner Correspondence Project sends to queer prisoners have been returned to sender with no explanation, despite clearly meeting institutional mailing guidelines. For the people who run and benefit from prisons, the wall is the wall, and that’s the point.

After our Innes Road Gazette mishap, I reached out to Olivia Wright, a scholar at the University of Nottingham who studies the history of prison zines. Her research has surfaced a long tradition of print resistance within the walls of prison. Early publications and proto-zines provided an underground internal forum for imprisoned people as early as 1900. Providing tips on how to individualize prison uniforms, or recording the events of a four-day protest at a facility — [zines by] incarcerated [people] have found innovative ways to resist the erasure and dehumanization of the carceral state,” Wright explains. They have also, not surprisingly, faced many challenges.

“Printing and distributing prison zines is sometimes a balancing act — ensuring that content won’t be censored or banned by prison authorities, while also remaining true to the publication’s aims and principles,” Wright notes. As we chatted, she zoomed out to walk me through the history.

“Since the 1930s, with the first in-house prison publications, you can see this [tension] develop and adapt,as [people] navigate the relative freedoms that the zine provides against the confines and influence of the carceral state,” says Wright, pointing out that the actual texts and images reproduced in these early pages were more localized and less confrontational. Later, allies on the outside would engender a departure from that.

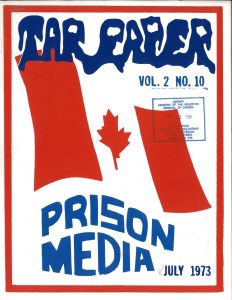

“As the process moves outside of prisons in the 1970s, and zines are [increasingly] edited, printed, and distributed with the aid of external organizations, the content becomes more overtly political and critical of the prison system,” Wright goes on.

This point is worth taking a moment to internalize. Prison zines did not begin with activists and artists going inside prisons to teach or do zine workshops. Rather, the first prison zines began in-house, crucial publications produced out of necessity and creative collaboration. They did not usually traffic in the now-familiar language of abolition or identity, at least not explicitly, nor were they seen as platforms for people to perform any particular vision of political purity for social status. This is in line with the prevailing attitudes in the mid-20th Century, which took a kinder, if condescending approach to incarceration based around reform.

For several decades, these publications ran with support from prison administrations, which often included equipment and financing. By the end of the 1970s, a harder view of imprisoned people that centered risk management eroded trust and dismantled those support systems. Around this time, groups of activists who were not incarcerated began to coalesce to provide support and solidarity for their allies and loved ones behind bars.

These images courtesy of penalpress.com

“Outside-directed” publications — those executed with guidance, support, or oversight from people outside of prison — tend to differ in content and aesthetic from “joint” or “inside-directed” publications, which are made with a particular prison or group of incarcerated peers in mind. In fact, Canada boasts a rich archive of inside-directed publications that are in and of themselves fascinating to read. Now, the age of so-called community arts or social practice collides with a boom in popularity for police abolition and, by extension, prison abolition activism. Though our Innes Road Gazette never took flight, plenty of other new and recent outside-directed prison zines are succeeding.

Quarterly prisoner/disability zine Sick of It takes the same approach as we did, publishing from a distance but soliciting contributions from folks inside. Incarceratedly Yours, based out of San Quentin State Prison in California, began collaboration before it began publishing, and is incorporating the inevitable challenges they face into the zine’s content.

No matter how you choose to do it, logistics inevitably become an issue.

From the outside in

In Manitoba, the Walls to Bridges Program brings incarcerated and non-incarcerated students together in one University of Winnipeg course — behind the walls. Classes are held at a number of institutions, such as Stony Mountain Federal Prison, which has a long history of prisoner publishing. While the class topics range from Community Development to Surveillance, Information and Criminal Justice, they all share a common final project: making a zine.

In Manitoba, the Walls to Bridges Program brings incarcerated and non-incarcerated students together in one University of Winnipeg course — behind the walls. Classes are held at a number of institutions, such as Stony Mountain Federal Prison, which has a long history of prisoner publishing. While the class topics range from Community Development to Surveillance, Information and Criminal Justice, they all share a common final project: making a zine.

The resulting zines tackle challenging themes with deeply personal content. A Tale of Two Journeys explores how racism in the court system results in intergenerational patterns of criminalization. I Am Surveillance compared the experiences of surveillance between incarcerated and non-incarcerated students.

I have long appreciated the unique talent and care of prisoner artists, on full display in the final zines from a 2019 Stony Mountain course. But as I flipped through, I was surprised to see them rendered in silk screen covers and collages. The logistics of getting half of a university class past prison security must be challenging enough — to say nothing of bringing in silk screens, inks, and cutting tools.

I asked Professor Kevin Walby how he and his class pulled it off.

“You have to say, ‘in Week Eight I am bringing in twenty pounds of magazines and you’re going to run them through the scanner three times,’” says Walby, explaining that planning and detailed communications start long before the course begins. “Then, I am going to open up the box in front of a staff member and they can look around it as much as they want.”

While magazines, glue, and rulers typically make it in the door without issue, x-acto knives and scissors are a definite no-go. Instead, students use rulers to fold and carefully tear the edges of magazines before pasting them down. Prison staff can manufacture security concerns to shut things down at a moment’s notice, so even something as basic as access to sinks for silk-screening must be negotiated six to eight weeks in advance.

While it can be frustrating to go along with invasive prison protocols, Walby explains that it’s necessary to get yourself in the door: “They like things reported in a command and control structure. If there are no surprises for [prison staff], they feel like they are in control.” He tells me, “There’s no other option. Whatever we have to do to make sure we can get the zines done.”

What’s remarkable about the Walls to Bridges zine project is that the bridging goes both ways — the program doesn’t just bring outside students in, it also often brings incarcerated students out and into the community. This is not always possible, however many of the Walls to Bridges students at Stony Mountain do have access to Temporary Absence passes, allowing them to attend planning meetings in the community.

“You don’t just want to go in there and it feels … like we’re a community for an hour, or two, but then we’re gone and they feel let down, not really part of the community,” says Walby. “We want everybody to actually be able to come to the university as part of the collaborative, creative process.”

Listen, respond, create

Listen, respond, create

It was Pride Week in Toronto, and the city was, as usual, abuzz and alive. But rather than join the shows, parades, and dance floors blanketing downtown, Sasha Tate-Howarth was celebrating with her incarcerated collaborators at a federal women’s prison. Tate-Howarth, of the Confluence Arts Collective, has been facilitating zine workshops in prisons since 2018.

The prison staff hadn’t planned any special activities to recognize LGBTQ2S+ communities in the prison, but people were telling Tate-Howarth they wanted to do something. So she adapted. Her usual zine workshop suddenly had a big theme, and the blackout poetry and collages it produced, while black and white, were otherwise bursting with rainbow charm.

“Ask people about the kinds of art they want to create,” encourages Tate-Howarth. “Then do your best to provide the resources for them to do it!”

Of course, not everyone has university credentials. Members of Confluence were required to do volunteer training, background checks, have their fingerprints taken, and memorize a list of forbidden items, made all the more complicated by differences between security levels.

“In the minimum [security] unit, people embroidered emblems, and in the max, people used paints,” Tate Howarth detailed, recalling how the latter’s rules forbidding sharps like needles and scissors had the unintended effect of making work go faster on an already tight schedule. She points out that precious work time could be taken out from under them at a moment’s notice.

“Sometimes we would find out on the day of, or on our way to the prison, or even once we were there that the max unit was locked down for the day, and we’d have to turn around and leave.”

Above all else, she stressed the importance of remaining aware of the power dynamics that exist when engaging in this kind of work. “There’s a tradition in the West of prison arts and prison theatre that is very much in collaboration with the prison industrial complex,” says Tate-Howarth. “I would urge anyone doing this work to be aware of that dynamic and work to resist it. Find ways to work in prisons where you aren’t complicit in dehumanization.”

In all, Tate-Howarth advised anyone planning on making zines with prisoners to be honest and self-critical. What brings you to this work to begin with?

You act concerned

In her article “Literary Vandals,” prison zine scholar Olivia Wright shares a poem from a 1972 issue of Clarion, produced at the California Institution for Women. It reads:

“You circulate newsletters / That print tears of my crying / You act concerned / Some of the time / You express the desire / To learn of this place / On visiting day / I don’t see your face”.

This poem describes the human consequences of what happens when creative projects with people inside turn out to be for the benefit of the person on the outside. It aches with the bitterness after someone builds a relationship with a person in prison, only to abandon them once the creative output has been completed or the grant report submitted. Given the responsibility that comes with initiating these kinds of projects, I have put together a few questions that people who are considering initiating zine projects with people in prison may want to consider.

Do I have existing relationships with people inside? If not, am I willing to put in the time to build those relationships and follow through with them even after the project has been completed?

Do I have existing relationships with people inside? If not, am I willing to put in the time to build those relationships and follow through with them even after the project has been completed?- Am I aware of the institutional rules and what is feasible in terms of correspondence, visiting, and accessing programming space?

- Am I putting time and space aside to ensure that folks inside are able to influence the direction of the project and its outcomes?

- Am I being critical and reflective of the power dynamics that exist delivering this kind of programming in prisons and working to actively resist the dehumanization that occurs in prison environments?

- Is the project I’m working on being produced in a way that incarcerated folks can share and use it?

- Am I taking the time to check in with folks inside about what ways they would like to see the zine used? Some people may be excited to produce zines but want to keep the final product for themselves and loved ones.

Whether you’re thinking about delivering programming or coursework involving zines in prisons, co-creating a project through correspondence, or using zines to spread information about prisoner organizing efforts, these questions are a good place to get started.

Beyond that, the most important advice I can give is to take your direction from the source itself — ask people in prison what they want, and what you can do.