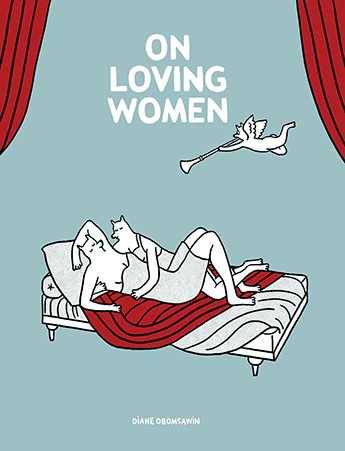

On Loving Women

Diane Obomsawin, 88pgs, Drawn & Quarterly, drawnandquarterly.com, $16.95 CAN

Montreal animator Diane Obomsawin’s second English language book is a quiet, articulate collection of short stories about first loves, adolescent awkwardness, and the often-uphill journey towards discovering and understanding one’s sexuality.

Like Kaspar, Obomsawin’s previous graphic novel with Drawn & Quarterly, On Loving Women is best described as staccato storytelling. Each of the book’s 10 vignettes is named for another woman; their narratives trace the early stages of their individual sexual journeys, from falling in love with secondary school teachers, fooling around on a train with a nun’s niece, and being shuttled off to a farm by one’s parents to remove the temptation of other women, to dropping acid, frequent underage encounters, and even a threesome.

Obomsawin’s art is characterized by its simplicity, with inelegantly drawn anthropomorphic animals standing in for humans. The style is unobtrusive, allowing for a bluntness of visual metaphor that perfectly matches the understated text, such as in the book’s final story and the employment of the parallel peacock imagery in one panel and lone hovering eyes in the next, drawing a line between the conflicting desires to be the centre of attention while also wishing to disappear into the crowd.

The collected stories feel strangely complete and incomplete at the same time; they’re first paragraphs to larger narratives the author has decided to leave off the table, choosing instead to focus on the discombobulating first steps of girls exploring their sexuality. While a few of the vignettes do stand out above the rest — “Sasha’s Story,” “October’s Story,” and “M-H’s Story” in particular — the overall quality of these micro-narratives is excellent. In their punctuated simplicity lies a disarming innocence; Obomsawin’s charming art and to-the-point writing help the book retain a certain levity in the face of heartache, confusion, and childhood expectations so unceremoniously checked. (Andrew Wilmot)