Erica Lenti and Sofie Mikhaylova are part of a millennial tech-savvy generation. Both 20, they’ve had access to computers since their pre-teens. They’ve both grown up with endless means to express themselves online, and yet when they each found themselves struggling to assimilate and express their queer experiences, they didn’t turn to blogs: they started making zines.

A couple for over two years, Mikhaylova and Lenti have made zine-making part of their relationship. Both journalism students in Toronto, Mikhaylova introduced Lenti to the concept of zines a few months before they started dating in April 2012. Mikhaylova has been making zines since childhood, and has always used them to express herself. Lenti made her first zine to work through the anger she was feeling about her horrible coming out experience.

Having dealt with peers outing and bullying her in high school, Lenti carried a lot of sadness and anger into university, and used those emotions to make a zine she originally published in a private online journal, and later in print. After making her first publication, she too found herself hooked.

The relationship between queers and zines is both long standing and deep running. Through the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, self-published zines were one of the few ways to get non-mainstream opinions and experiences out into the world and queer folks relied heavily on handmade art books to help tell their stories and build communities based on similar experiences. This tradition has carried into the present, perhaps because zines have been integral to queer history and storytelling. Zines are cheap to make, personal, and require no outside approval or screening process to be created and put out into the world. Passing around tangible pieces of queer history and narratives builds ties within the community, and ensures that no voices are left unheard.

“I think queer people get the short end of the stick when it comes to visibility in the media,” says Lenti. “We’re constantly hearing about queer people through a heterosexual (usually white) voice and that’s obviously problematic. I think zines provide the platform we need to get our stories told in a totally uncensored and creative way.”

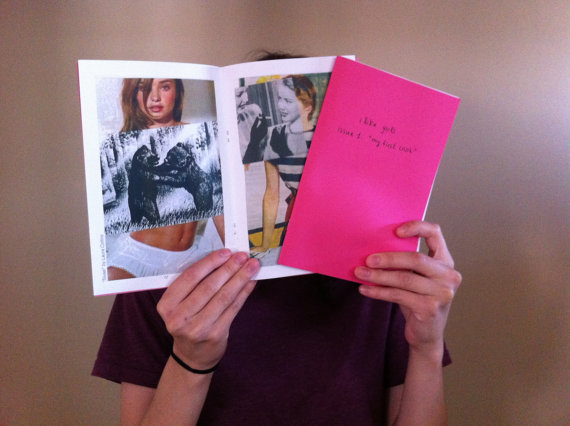

And so they started their own independent publishing house — House Hippo Press — to rectify this imbalance, making room for more self-expression from female- identified queer people in their community. I Like Girls Issue 1: My first crush is the first zine published by House Hippo, and the beginning of a themed series they hope to develop. Between the zine’s pink covers lie emotional, honest and sometimes painful outpourings of seven girls who like girls, their voices bound together by a shared experience. The first issue of I Like Girls includes stories such as teenagers bonding online over Tegan and Sara, an illustration of a girl staring up at a massive vagina called “When I saw the Origin,” collages of women, wildlife, and vintage photos by Laura Collins, and a lot of painful first crush memories.

House Hippo Press follows a long tradition of queer DIY zine-making that originated in the early ’70s in New York, with the printing of Ralph Hall’s Faggots and Faggotry, a zine filled with line drawings, poetry, and gay politics on cheap coloured paper. Later, a series of popular Canadian zines would surface, like Mike Niederman’s Heartwar Fuckzine series, or the Toronto Rag by Bill Elderado. These zines were colourful and very political, fitting in well with the world of selfpublishing. During the ’80s, queer zinesters and DIYers banded together with underground filmmakers and punk musicians, forming a counterculture community called “Homocore” that eventually came together in Chicago in 1991 for the first ever queer zine convention, called SPEW.

Chris Landry knows a lot about the history of zines: queer zines in particular. A co-op librarian at the University of Guelph, past employee at Western University’s Pride Library and former volunteer at the Toronto Zine Library, Landry helped develop Western’s Queer Graphica project:a collection of zines, comics, graphic novels and art books that helps to tell a more full, diverse story of queer history with a Canadian focus.

As a librarian-in-training, Landry (who is also a zine reviewer for Broken Pencil) sees himself as a caretaker, researcher and advocate for queer zines. “In terms of content, I would say [the way it’s delivered has] certainly changed to reflect the ways access to media has changed. I think the idea of queer subjectivity — opinion, cultural dialogue, debate, news, art, drawing, storytelling, kink, politics, etc. lacked a real place in the media in the ’80s and ’90s, and zines were really a way for folks to express themselves,” he says.

Pointing to the ’90s zine Holy Titclamps out of San Francisco, Landry notes that its regular supplementary review zine, Queer Zine Explosion, provided a centralized space to gain access to the queer zines of the day. “I don’t know if things still work like that today,” says Landry. “When I was building the collection at the Pride Library I used message boards on We Make Zines, Etsy shops, zine distros, other zines, and asked questions of people who were in the know to find out what was going on. So, I guess I would say that in this age things are more decentralized.”

Though queer rights and visibility have come a long way over the past 30 years, zines still function as a crucial piece of the past and present, acting now as a way to record personal stories and capture new history in the making. Queer zines have captured the un-recorded and otherwise forgotten stories of their times, acting as a window into our own histories and personal politics for future generations of queer creators. They also act as an effective tool to help queer zinemakers unpack and process their own experiences coming out of the closet and into the pool of dating, sex and sexual identity.

Eric Kostiuk Williams has been making comics and zines since high school, but only started to receive an enthusiastic response when he moved from Ottawa to Toronto for university. While finding his footing in Toronto and exploring the gay community, Williams started a series called Hungry Bottom Comics based on his personal experiences as a queer person in the city. “As I began considering my own sexual preferences and personal politics, I started becoming aware of a dichotomy between ‘gay’ and ‘queer’ identities,” he says. “After going through a handful of negative dating experiences, I decided to take a step back and reflect on what I’d gone through during my time so far in Toronto by way of one-page autobiographical comics. As the months passed, I created more and more of these, and eventually they started coming together into a more cohesive narrative.”

“As queer people, we’re often the makers of our own culture,” says Kostiuk Williams. “Zines have proven themselves time and time again as being a great tool for queers to destabilize hegemonic cultural narratives. As visible, tangible objects, they have a way of affecting physical communities and creating a sense of solidarity, which is of crucial importance to queer people, who often struggle to feel safe in their everyday lives.”

Now working on his third and final installment of the Hungry Bottom series, Williams hopes to collect his work into a bound book later this year. Though he will continue to update his Tumblr and online presence, he is more interested in making tangible art and publications, a tradition he believes is crucial to continued development of the queer community. Some of the most important moments in Canadian queer culture have unfolded because of zines, he says. Case in point: in May 1993, SPEW 3 came to Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto. The event wasn’t just about buying and selling zines, it was a space for queer zinesters to talk and make connections. Canada, especially Toronto, played a huge part in the queer zine and DIY movement, with well-known artists like Bruce La Bruce and GB Jones banding together to create collectives like “The New Lavender Panthers,” publishing the zine JDs, and bringing queer issues and identities to an otherwise very straight punk scene.

Unlike the mainstream gay movement, homocore DIY zine culture was more radical, and openly resented the “commercialized” LGBT community and its desire to be accepted in the straight world. The culture surrounding queer zines in Canada is constantly growing and evolving. In 2013, Toronto had its first exclusively queer zine fair, TQZF. Held at a small community centre in the city’s west end, TQZF provided a place for the queer zine community to come together and share their work in a safe and accessible space. The organizers provided vegan, gluten-free food, and made both the fair and after-party alcohol free to ensure attendees were comfortable. Vendors included Shameless Magazine, Queer and Trans* People of Colour Distro, Crooked Fagazine, and Kate Lavut, an artist whose zine Chico tells the story of her shaving her head and going to Mexico dressed as a boy. Eddie O, one of three founders of the event, says their first year was bigger than expected, and very successful, but that the organizers still have a lot to learn, including how to address many issues within queer zine culture itself.

“There is an overrepresentation of white queer zinesters, which frequently ignores and undervalues experiences of queer and trans people of colour who write and produce zines,” says Eddie. “Its been a big learning experience for us, as white organizers and queer zine makers, to realize that our experiences are going to be validated more than others, and that in trying to build a fair that strives to be as inclusive as possible, it is vital to acknowledge the power structures in queer zine culture and try our best not to perpetuate them. We have taken the feedback and criticism we’ve received and will use them as building blocks in our future organizing.”

Queer POC artist and activist Elisha Lim — the artist behind 100 Butches and Sissy Calendar — feels history is largely to blame for this divide. As someone who has made zines about queerness, race and gender; directed Montreal’s first Racialized Pride Week and lectured on race representation and gender neutral pronouns, Lim doesn’t feel particularly connected to the queer zine scene. “I guess [it’s] because I don’t identify with queer white subcultures like punk, anarchy, or riot grrrl,” Lim says. “I’ve never really depended on the queer zine community. I just make zines I care about and market them on Facebook and Etsy. I don’t pay attention to the scene. Instead I’ll tell you about zines I love: Race Riot, POC Zine Project, Cristy Road’s zines, Leroi Newbold’s Bcozwehaf2.”

Alvis Parsley, a Toronto-based zine maker and performer with a strong focus on exploring identity issues, moved to Canada from Hong Kong and just made their first zine about Craigslist encounters called What happens when the TOMBOYISH FAGGY GENDERQUEER SISSY-IN-HEART SOFT BUTCH DANDY BOI (who rolls up their pants and sometimes shorts) seeks out?. Their zine touches on human interconnection and strangers in the internet age “with main themes of straight cisgender men fetishizing ‘lesbians,’ white guys fetishizing Asians and vulnerability when you put yourself out there to be judged, especially when you are not ‘typically’ sexy,” explains Parsley who feels, regardless of the content, queer zines are an important part of queer history.“Some of us have a lot to say, whether it is about politics or our brunches,” they say. “I think it is important to the queer community as independent analogue publishing is a major way to create our legacy.”

Just as the queer zine scene has continued to grow, prosper, and become more well-known here in Canada, it has also continued to expand in America. This past winter a portion of the hugely popular LA Art Book Fair was dedicated to a Queer Zines Exhibition. The exhibition contained a massive collection of queer history, with over 200 zines and handmade queer works spanning from 1970 onward. The inclusion of only art-based queer zines resulted in a stellar collection of hand made, print publications, like Translady Fanzine by Amos Mac (the founder of Original Plumbing), and Poser1, a project by Canadian Ho Tam, featuring photos of monks in Bangkok. Tam is a Vancouver-based cultural worker, curator and artist. On top of his own personal zines, he recently created a project called XXX Zines in the hopes of fostering more print-based work within the art community. He reached out to some of his favourite artists from all around the world, and together they created a set of 16 limited- run publications. Printing and binding each zine at home, Tam funded this project himself in the hopes of putting something different and provocative out into the world, giving complexity to the modern queer dialogue and exposure to lesserknown queer artists. Each zine deals with completely varied subject matter, from William Yang’s experience growing up and coming out as a gay man of Asian decent in Australia, to Jack Butler’s drawings on sexual play and personal growth. Tam thinks the need for queer zines isn’t going anywhere.

“Queer zines in any form, whether in print or as a blog, are just as relevant these days as [they were] years ago,” he says. “Outside of the Western countries, the rest of the world is just opening up. For example, the artists in China are just exploring the zine format now, after years of persecution and prohibition of independent publishing. You would not believe how popular those zines are.”

Toronto-based artist Coco Riot also thinks that zines are an important forum to document queer history and help the community’s narratives grow and be more widely understood. “Zines are important to any community that doesn’t [always] find their voice expressed in the mainstream media and academic publishing. Zines are important to share experiences that we cannot find in books that we cannot afford, or, for example, in my case, I cannot fully understand.” Riot is a queer Spanish artist, and they say they have trouble understanding academic reductions of queer history because of both the language barrier (English is not their mother tongue) and the use of academic language. “Zines talk about our experiences and provide accounts of changes in our communities, our politics, and our self-healing processes, because they are fast to produce and have multiple authors and voices. I think if we expand our ideas of ‘zines’ to think of zines as any form of experiential account for people by the people, we will see that zines, oral history, community theatre, etc. have been done forever to document non-mainstream forms of living,” they say.

Mikhaylova and Lenti couldn’t agree more. “I [participate] in the queer/feminist community online and there are so many zines made for queer/LGBTQ people,” explains Mikhaylova who, with Lenti, plans to continue attending zine fairs as House Hippo Press and building on the narrative they have started with their I Like Girls zines and, more recently, a queer feminist poetry zine by Helena Kaminski. “It’s truly amazing how putting people’s stories out there can help others going through a struggle. It’s a form of empowerment… and I find a lot of queer publishing also has a similar outlook.”

Having both covered queer issues in their journalistic work (Lenti just wrote about queer access to healthcare, and Mikhaylova wrote a piece about visiting her family in Russia as a lesbian), the makers behind House Hippo Press know there is still a lot of work to be done concerning LGBTQ rights, and think zines are a huge part of making that progress. Mikhaylova adds, “I think a lot of zines are propelled by anger (I hope), and I think that queer zines, at least for me, come from this inner need to put my voice where I know it deserves to be. I think, perhaps, issues motivate zinesters but not all zines are about serious issues. Just because a show features an LGBTQ character doesn’t mean they’re LGBTQ friendly. The fight is never over. Queer zines are not a way to be complicit within what limited media there is for LGBTQ people. They’re a way to make our own media.”