Atom Cheung was a single body in a sea of protesters standing on Hong Kong’s Harcourt Road. It was July 1, 2019 — the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from British colonial rule to China. That day, 550,000 demonstrators gathered in this major traffic artery to show their defiance against the Beijing government. The police put the figure at 190,000. Cheung watched as a contingent of protesters stormed the Legislative Council Building. Nearby, others were getting step-by-step instructions on how to handle the inevitable clouds of tear gas: Put on your face mask. Don’t run backwards if the tear gas comes because you might trample people behind you. Use this plastic wrap on your arms to protect your skin.

“And that was the moment that it hit me. This is too much for me. I don’t know if I can handle it,” Cheung says.

From here, he started thinking. At the age of 39, if he could no longer handle being the guy confronting cops, how else could he contribute to the movement against authoritarian Chinese rule? Within weeks, Cheung was presenting art and zines birthed out of the Hong Kong-based democracy movement on the other side of the globe. This was it: the Freedom-Hi exhibit.

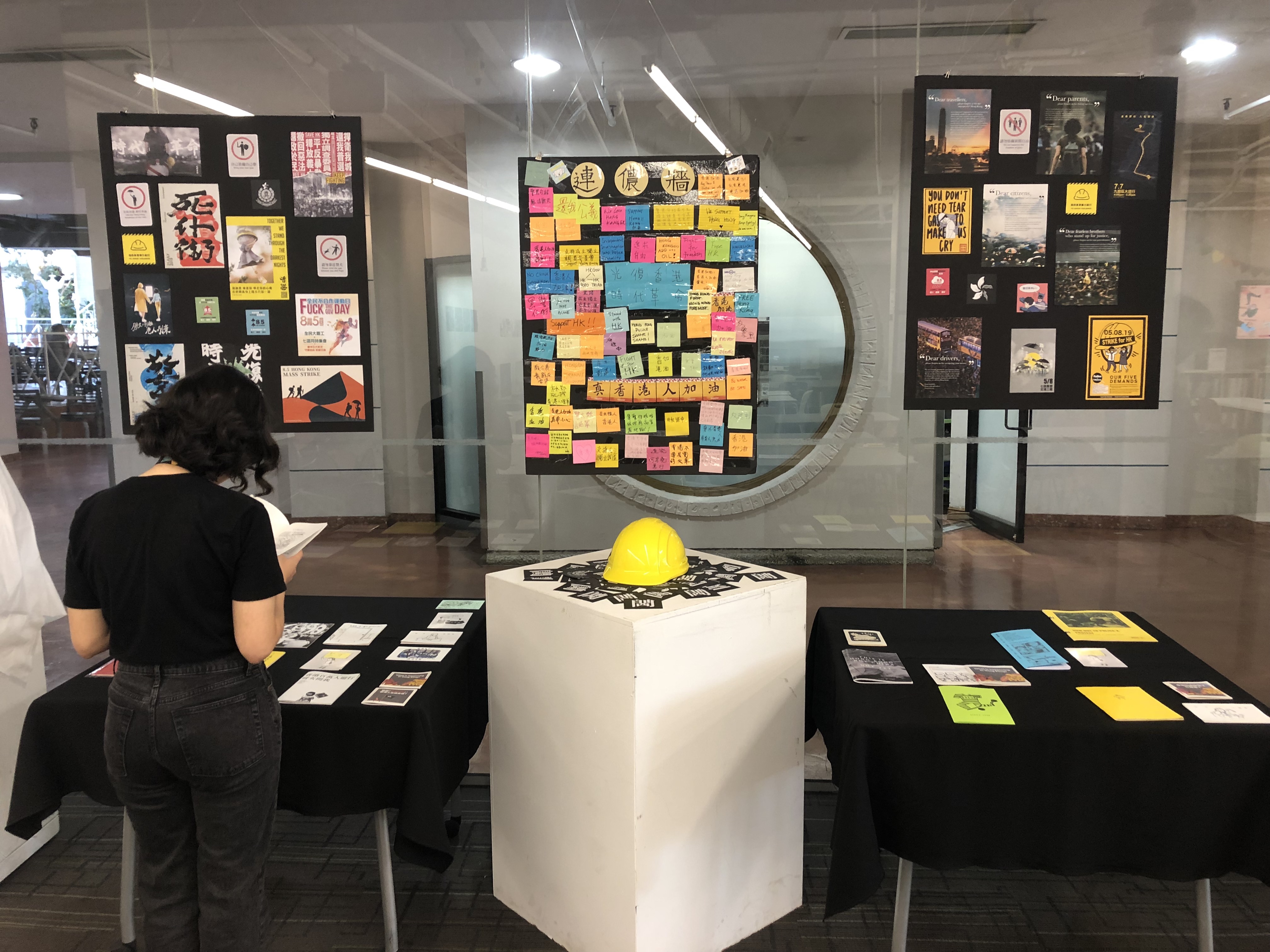

In early August, Atom introduced his show to a mixed crowd of activists, journalists, and artists at the Ontario College of Art and Design’s (OCADU) zine library in downtown Toronto. He gestured at the 50 zines on the display tables behind him, framed by graphics, timelines, and paintings hanging from the walls and ceiling.

“I see publications like these as a very good vehicle for self-expression, for spreading information, and to get around censorship,” Cheung says. “And obviously, a very creative way of resisting against the situation we’re in.”

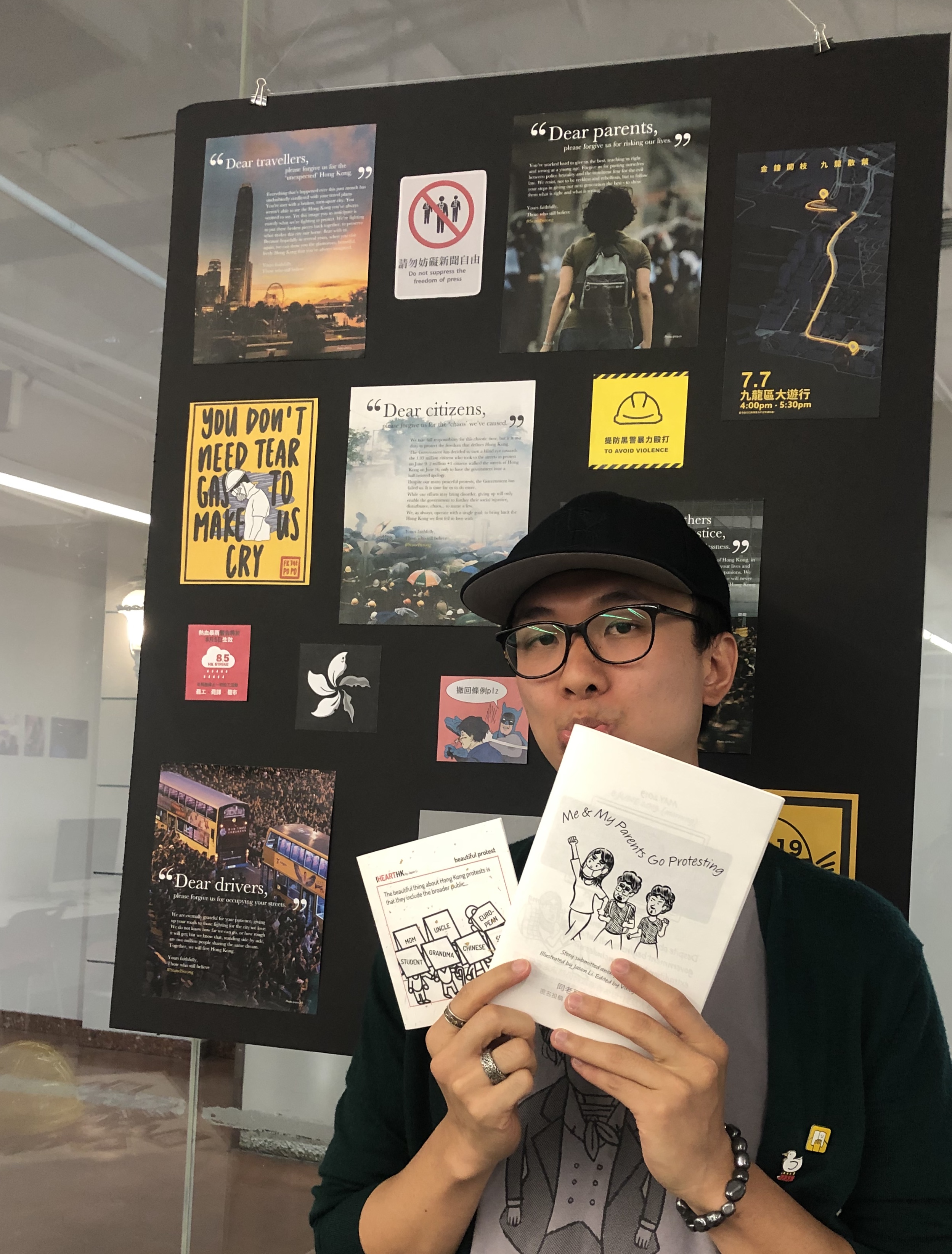

For Cheung and the other contributing artists, Freedom-Hi’s collection represents a different entry point for understanding the ongoing demonstrations in Hong Kong. In his opening remarks, Cheung said that these pieces are meant to be a more intimate way into the protests, featuring titles like “Me & My Parents Go Protesting.” Hong Kong-based cartoonist Jason Li helped illustrate this anonymous submission about one family’s varying levels of enthusiasm for the protests that have demanded the attention of observers from around the globe.

“I thought that it really captured some interesting, funny, but also painful family dynamics that happen in a protest,” laughs Li. “Even when they’re on the same side.”

Li’s zines draw on Hong Kong’s long history of print and manufacture. Though many printers have moved to mainland China, copy shops still thrive on the island. “There is still a culture of cheap printing,” Li says. “There are many places that advertise same-day name card printing, which you don’t see anywhere else.”

Zines also offer an important alternative space for Hong Kong publishing, according to Li. “Many of the large publishers in Hong Kong are subsidized or indirectly subsidized by the Chinese state,” he notes slyly.

“The complicated thing in Hong Kong publishing is that there is a vertical integration of publishers and bookstores … Reporters have found that many of the big bookstore chains are basically living rent-free because the spaces are owned by people that are directly or indirectly tied to the state in China, [affecting] what they will or won’t publish.”

Liu Nganling is a multidisciplinary artist who uses the pseudonym Siu Ding. She says that self-published zines offer an important means for reclaiming Hong Kong’s history. “Every time when we read history, there’s only an official way to see it,” she said. “But this is the time to write it our way, and different people have different methods to do it.” Indeed, SiuDing’s zines often speak back to history, and Freedom-Hi’s catalog documents Hong Kong civil moments since 1989.

Artist Ricker Choi primarily uses acrylic painting to comment back on the narratives of Hong Kong organizing. He says the medium is a release, and a way to archive events. His painting Cries of Hong Kong adapts Edvard Munch’s The Scream, but in Choi’s painting, the classic screaming figure, mouth and eyes agape between cloying palms, appears to be the target of two figures in white. Choi is referencing the July 21st attack in Yuenlong, a neighbourhood bordering mainland China, where a mob of men in white attacked civilians and pro-democracy protestors indiscriminately. Police were, for once, nowhere to be seen.

To some, the Freedom-Hi exhibit reads as an expression of the post-internet movement, a response to the Internet’s impact on art, culture, and communications at large.

“I [wanted] to offer a more reflective, slow-paced experience, because online news is very fast,” Cheung told Broken Pencil. “You’re constantly swiping on your phone. People talk very fast. Things are happening very fast. I think [zines are] a chance to slow down and to go deeper within, but also explore wider.”

Liu agrees that mainstream media’s coverage can be a sensory overload. “I couldn’t sleep, because when you look at the videos, it’s very sad,” she said. “I try to avoid some of the information, because it’s too much.”

“For more than 10 years, I joined different events and took pictures,” says Liu. She does use art publishing as a way of documenting the front lines of history. But the process also allows her to step back and reflect on the past. Her zine VIIV, part of Freedom-Hi, takes its title from the Roman numerals for 6/4 — the date of the infamous 1989 Tiananmen Square Crackdown. The zine documents the artist’s yearly performance art interventions in public space, meant as a reminder of the ongoing effects of that conflict. Another zine, Pearl of the Orient, chronicles four major protests in Hong Kong: The 2010 Anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link Movement, Occupy Central of 2011, the 2014 Umbrella Revolution, and finally, this year’s Anti-Extradition Law Movement.

Liu says that making zines and art has helped her not only express her feelings on contentious issues, but also to feel more certain about her participation — despite how risky attendance might be. “It makes you more comfortable and confident to be there because you already [digested] the whole thing,” Liu says.

Freedom-Hi — it’s a curious name for an exhibition. To an outsider, it may seem like an optimistic greeting, as in “Hello, freedom!” But in fact, you can find thousands in the streets of Hong Kong donning t-shirts emblazoned with the phrase. It’s a response to a viral video where a Hong Kong policeman was caught swearing at a protester on the run. The phrase is a transliteration of the cop’s exclamations, jeering and calling him a “pussy” for begging for freedom — “Hi” in Cantonese means “pussy” or “cunt.”

Freedom-Hi — it’s a curious name for an exhibition. To an outsider, it may seem like an optimistic greeting, as in “Hello, freedom!” But in fact, you can find thousands in the streets of Hong Kong donning t-shirts emblazoned with the phrase. It’s a response to a viral video where a Hong Kong policeman was caught swearing at a protester on the run. The phrase is a transliteration of the cop’s exclamations, jeering and calling him a “pussy” for begging for freedom — “Hi” in Cantonese means “pussy” or “cunt.”

The t-shirts are the work of the Hong Kong Artists Union (HKAU), formed in mid-2016. They printed and distributed the t-shirts, aiming to reclaim the insult.

“Yes, we are a group of pussies striving for freedom,” says Wong Ka Ying proudly, a member of HKAU.

Wong says the formation of HKAU has helped to organize the local art community’s protest efforts. Their work this year has included sketches of police abusing their power, virtual reality videos from protests, sound walks, t-shirts, and an open letter calling on artists to go on strike by vowing to stop creating art for commercial purposes, and channel their work towards political ends instead.

Wong said that for her, art is another way to bring people in the movement — which is almost everybody — together. HKAU began holding workshops on weekends to give artists and non-artists alike a space to create props and signs. However, in the face of recent violence, art, and independent publishing is also itself a place of refuge.

“I think art is more like therapy and healing now,” she says.

Atom Cheung encourages this type of introspection through the exhibit, particularly for the Hong Kong diaspora in Toronto. “I hope you guys come out and really take this opportunity to learn more about Hong Kong,” he said. “I’m sure through this process, not only will you learn more about the city and its people, but also about yourself and your connection with Hong Kong.”

Toronto was just the second stop of the Freedom-Hi! Zines from Hong Kong’s Civil Movements exhibition tour. Stops are planned for Montreal, Zurich, Taipei and Melbourne. Learn more about the project at zinecoop.org