Check out profiles of more countries in our Global Zine Report.

“Shanghai is really high-pressure, everyone’s running after the money all the time,” Zovi Weng told Broken Pencil over a noisy WhatsApp call earlier this summer. Loud conversations, car horns, and static confirmed his characterization of the bustling city. “Everyone is overworked, but I wanted to find a place to actually have fun.”

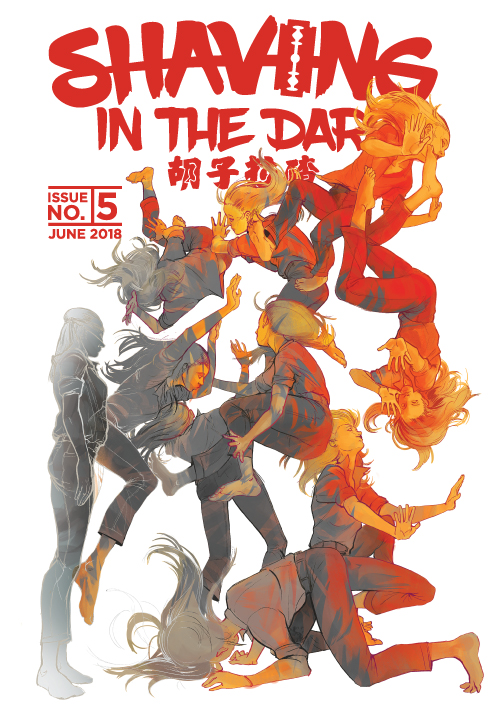

Instead of finding it, Weng and his friend, Jar Mark Caplan, decided to make it on their own. They had already asked for submissions for their Shaving in the Dark Zine, an underground platform for comics. But when they started hosting Drink and Draw events for contributors to meet each other, they saw a community form.

“It kind of happened by happy accident,” Weng laughs. Getting a zine off the ground in Shanghai can be tough, Weng and Caplan told me. There are stern government regulations about publishing, and you have to be discreet.

“Doing anything indie in publishing is really difficult with the regulations,” says Caplan, and getting an official publishing license is almost impossible. “But I feel it’s gathering steam for sure… The demand is there.”

Most of the zines they encounter in Shanghai are apolitical, for obvious reasons. Censorship in China is stern, and you have to play the game. “We know what we cannot do,” says Weng. “It’s kind of in the air, this sort of self-censorship.”

Rather than address issues head-on, zines and art about identity and personal stories projected into the realm of suggestion and fantasy are much more likely to survive than a straight-up punk or radical zine.

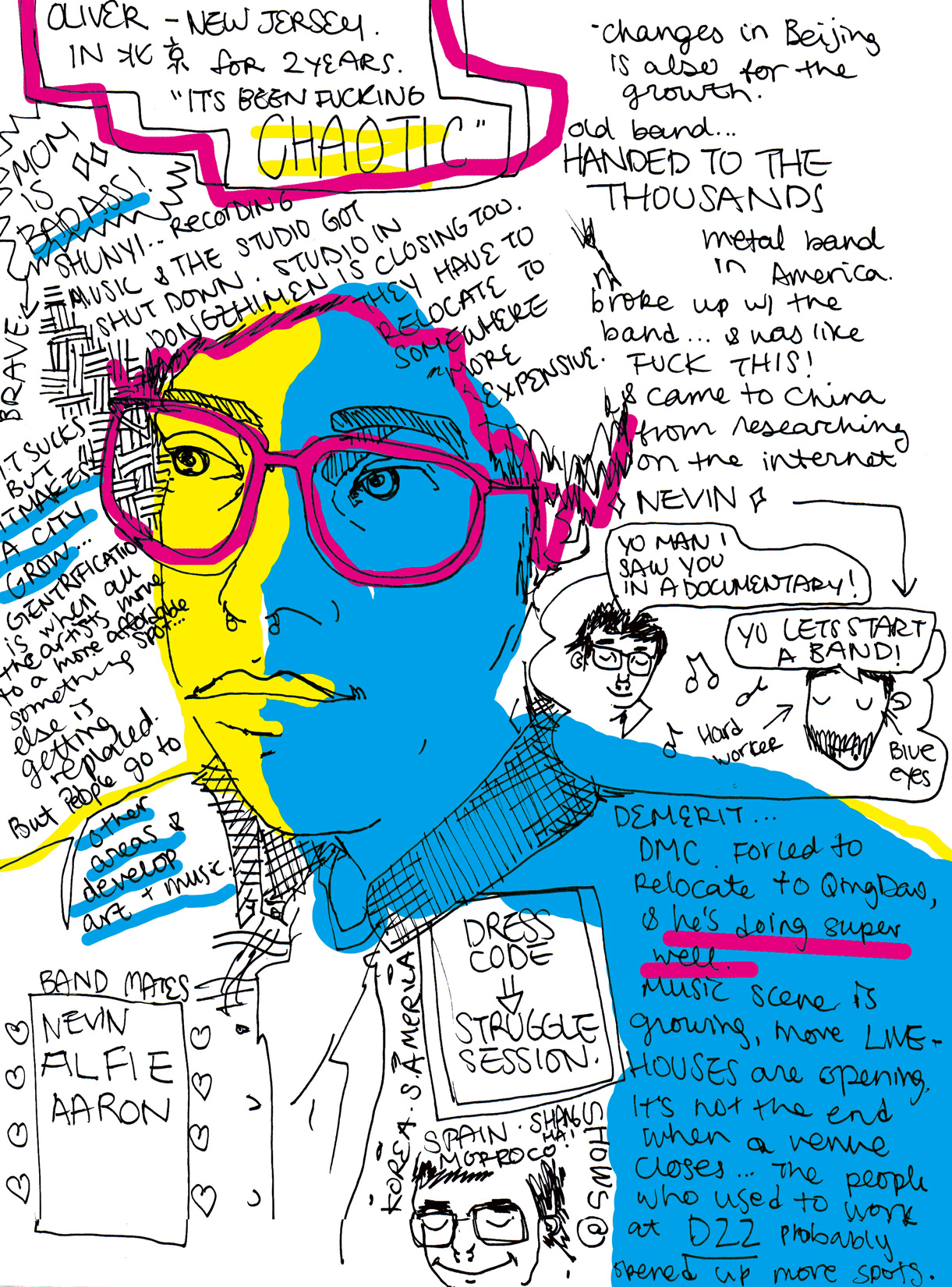

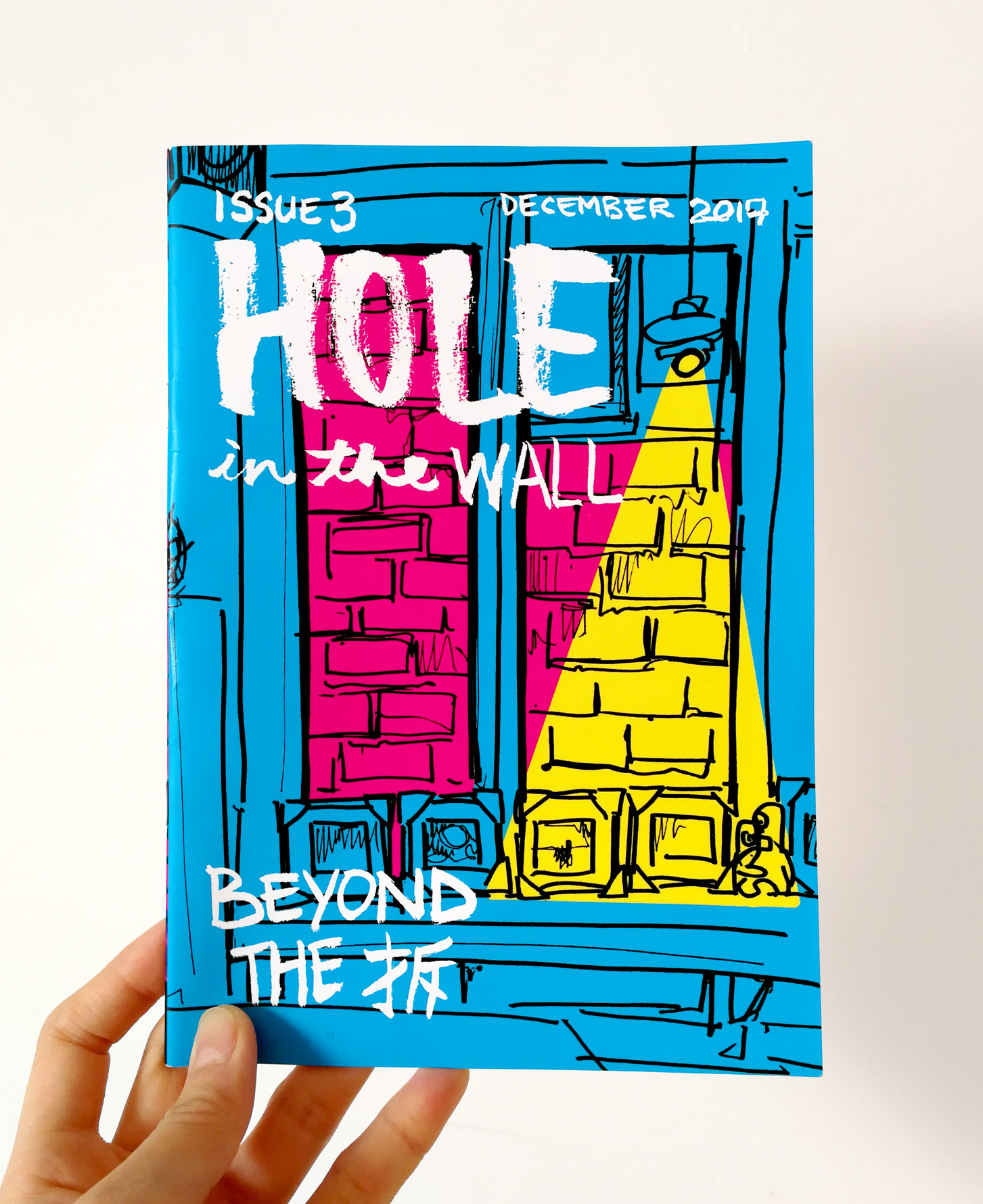

Yet, 1,300 kilometres north in Beijing, Hole in the Wall Zine gets away with a little bit more. The zine, started a bit over a year ago by friends Jinna Kaneko and Shui Wang, is meant to capture the large-scale, government enforced displacement that is rapidly transforming Beijing neighbourhoods.

“They evicted everyone who isn’t a Beijing person,” explains Jinna. “From little, small food sellers to cigarette sellers to people who sell flowers.” Jinna and Shui watched small businesses and underground spaces disappear, especially the hidden alleyways and courtyards known as hutongs. They decided to document them by interviewing the people affected and drawing portraits of them. They’ve found an audience for their project in the DIY and underground arts scene of Beijing.

“The underground music scene is huge. You’ve got punk, you’ve got rock, you’ve got hiphop, you’ve got all these local artists — very down to earth people,” describes Wang. The music scenes and other underground culture makers are linked primarily through groups on the social media platform WeChat. But while digital connections keep the scene thriving,

Wang and Kaneko wanted to make something you could hold.

“As artists, we like tactile things, and we did start through offline publishing,” says Wang. “We still all gather together and support each other. We like to see a live band or an art market.”

“That also creates a connection, a human to human connection that we can’t really get online,” adds Kaneko.

As with so many zine cultures, self-publishing in Shanghai and Beijing seem to be connected to broader communities of underground media makers. While strict oversight from the state keeps people careful about publishing projects, an emerging zine scene makes space for subtlety.

Featured photo by Nathan Wang

CHECK OUT: