All images are excerpts from “First Aid for Typewriters” by R.M. Kasten (Popular Science, 1941)

All images are excerpts from “First Aid for Typewriters” by R.M. Kasten (Popular Science, 1941)

I used to think of my typewriter as a quaint alternative to the computer. That was before 2018, when Sarah Jaworski and I created our shared micro-press, Wyrdsmyth Press. We set out producing batches of broad- side poems on a typewriter, and we quickly noticed how using the machine actually changed the work we were making in unexpected ways.

It can take some time to find your footing, but here are a few tips I picked up while trawling the internet and chatting with my mum that might help zinesters and chapbook creators as they dust off machines of their own.

Managing mistakes

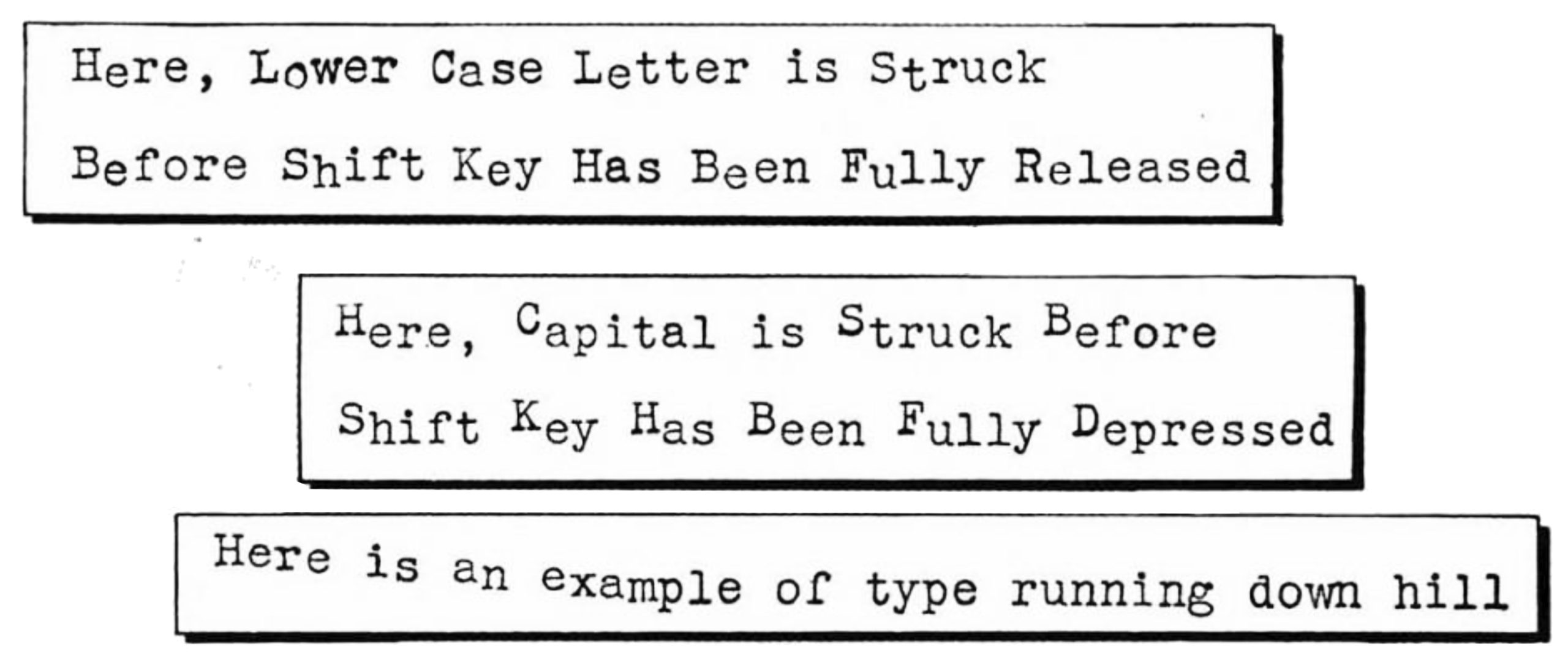

Sarah recently compared typewriting to carving a block of linoleum for printmaking, an insight I found really useful. Indeed, a typo can be as frustrating as a slip of your carving tool. But mistakes inevitably happen. When they do, you have two main options: either incorporate the mistake into the piece or discard the whole thing and start over. You can sometimes type right over typos (“o” and “e” are usually fairly forgiving), but crisp letters come from accurate typing. Practicing typing basics can increase your precision, but I found that changing my posture while typing did the most to limit the number of times I’d hit two keys at once or jam my fingers between keys.

Typewriter care and condition

Your typing accuracy is also impacted by the condition of your machine. Chances are that you have an old typewriter that didn’t come with an owner’s manual. All the second- hand typewriters I’ve used have needed a little care before they’ve worked smoothly. You can, of course, have your typewriter professionally serviced, if there’s a typewriter repair shop in your area and you have the money to spend. If not, you can find plenty of resources online. You might begin by perusing The Classic Typewriter Page, which compiles general service guides and digitized user manuals for a variety of makes and models.

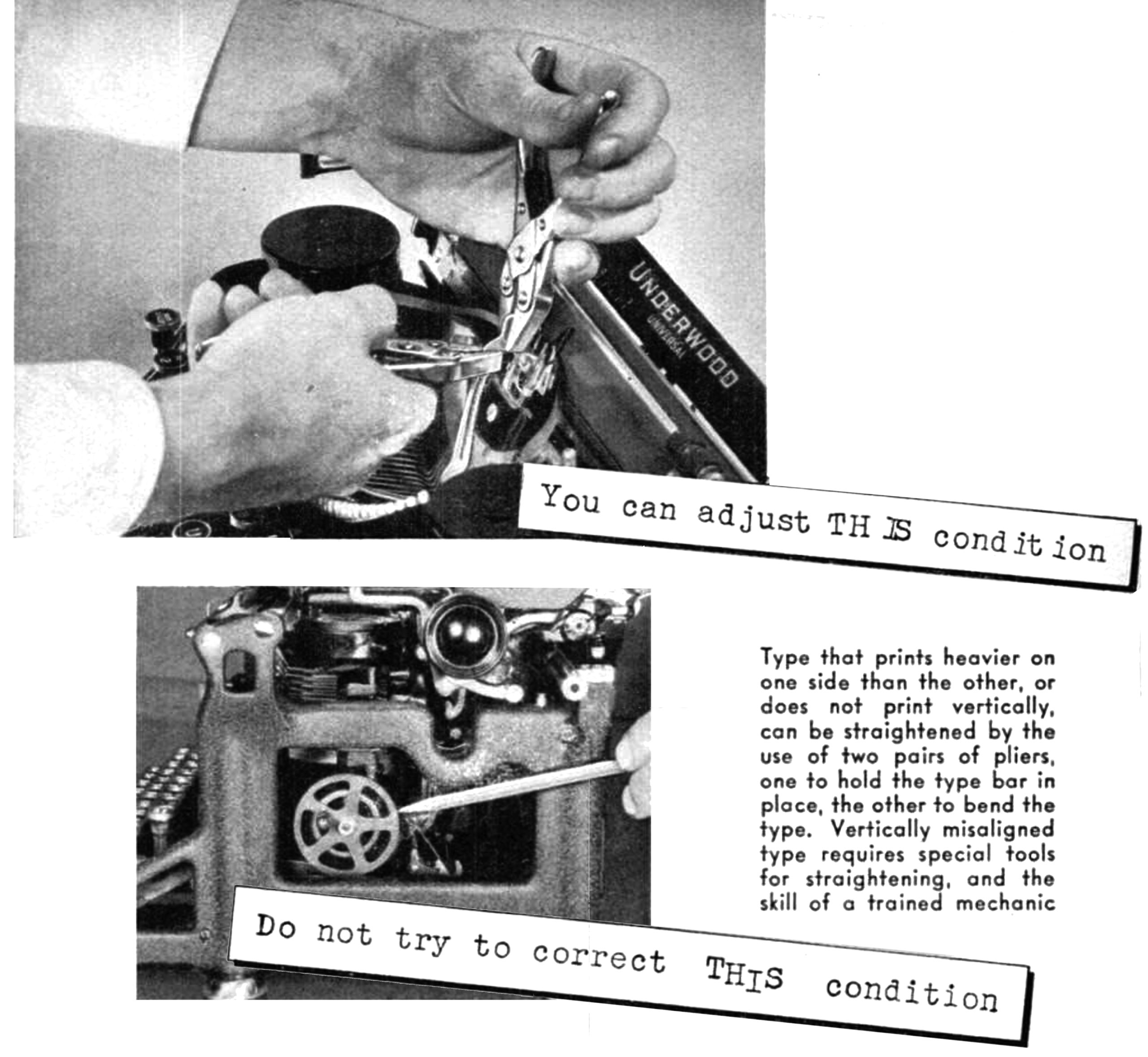

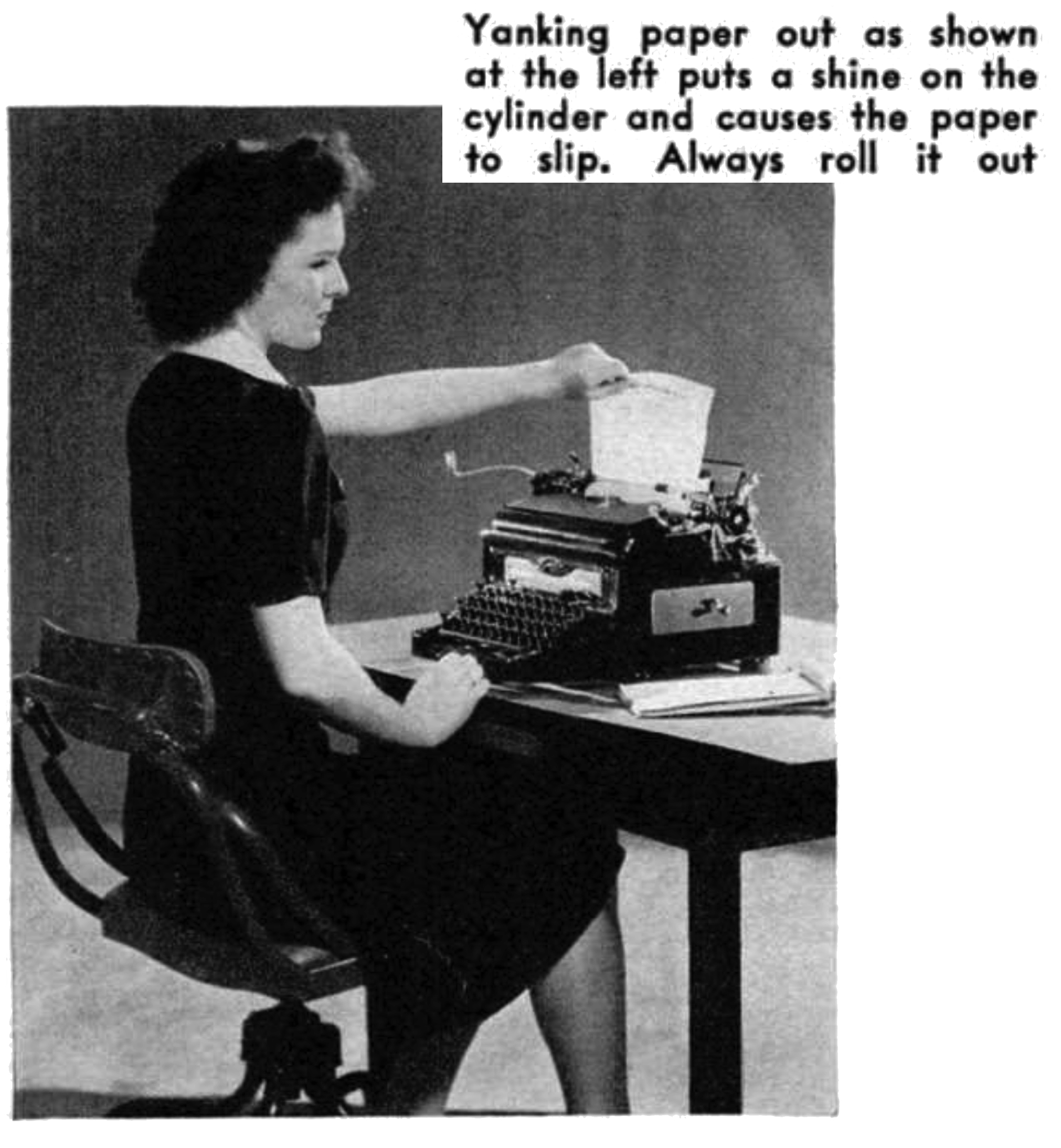

One prominently featured guide there is R.M. Kasten’s “First Aid for Typewriters” from the May 1941 issue of Popular Science (excerpted in this piece and available in full here). Kasten’s illustrated introduction to service and repair gives a brief overview of maintenance, basic fixes, and troubleshooting.

However, if you are going to try to fix a specific typewriter, I suggest taking reference pictures to better understand how to put things back together. I also strongly recommend placing small parts in containers to avoid misplacing them while you work.

Pay attention and have patience

Unless you overhaul your typewriter completely, you’ll have to work around its foibles. Work slowly and pay attention to what your machine is doing as you learn these quirks. Many issues I encountered early on could have been avoided had I been more familiar with my typewriter’s settings. For example, sometimes the carriage just wouldn’t budge. The most common explanation? I’d knocked the settings for the margins and ribbon with- out noticing. At first, I’d set off typing without giving these parts any thought, but I learned to always check them before beginning. Paying attention to the mechanics fundamentally changed how I use a typewriter as I think more about what sets it apart from other tools.

Space, grace and the letter case

Once I was aware of the margins and scale, I learned to think of typing in spatial terms. I started to consider line lengths while typing, to count the characters and spaces that would fit within borders, and to play with page

layout. The typewriter’s constraints pro- vide creative challenges that make typing more than a cheap alternative to typesetting or a way to repackage exist- ing texts as vintage chic.

Despite being machine-made, typewriting keeps a handmade quality. It can’t be remixed, reworked, or reproduced as easily as digital work. This may be frustrating at times, but it also adds value to your art. The time required to overcome a repeated error, or the effort of getting the page layout just right — these are worth it when holding that final copy. However, the pieces that subtly incorporate errors feel the most handmade to me. They demonstrate the creativity I associate with typing, but preserve a trace of the human element of their production. Each print is something special.

Ben Toner is an Ottawa-based poet and printmaker. He is one part of Wyrdsmyth Press with Sarah Jaworski, a micropress specializing in type-written poetry broad-sides featuring hand-pulled linocut prints. Ben also runs #fortunesandfavours, a micro-poetry scavenger hunt on Instagram.